The Practical Art of Prototyping Sensors

A team of about 200 researchers at a lab in Atlanta toils on sensor prototyping and testing. The lab specializes in building prototypes and improving legacy systems used in a wide range of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and electronic warfare applications.

Much of the work is sensitive at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) Sensors and Electromagnetic Applications Laboratory (SEAL), in part because the word “applications” is central to what it does. Unlike the basic research and development conducted at some military and national labs, applied research often is not made publicly available. “Any time we’re looking at applications—which is where we’re focused—that tends to not be in the public domain,” explains Mel Belcher, SEAL director. “We tend to be very application-focused. We don’t get credit for our labor until we actually get something integrated with a legacy system or get a sensor built and ... show that it can collect data.”

Because of the nature of the work, Belcher must be circumspect with what he reveals. He confirms that the laboratory has contributed to the war effort, for example, but he will only go as far as a simple “Yes.” Still, he touts SEAL’s ability to push out prototypes on behalf of the U.S. Defense Department and military services. “Our culture is really about building things and technology insertion, probably much more so than most of the labs out there. What drives our growth is really prototyping,” he says.

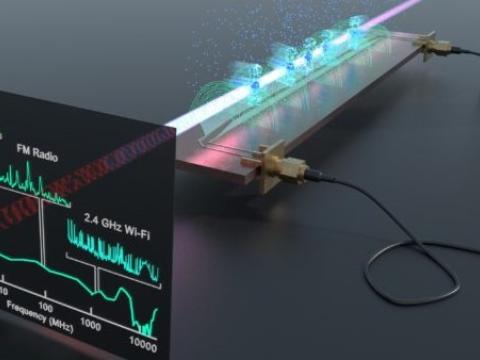

According to the GTRI website, SEAL research falls into four primary areas: intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR); air and missile defense; foreign material exploitation and electromagnetic systems; and electronic attack and electronic protection. SEAL investigates and develops radio and microwave frequency sensor systems, emphasizing radar systems engineering; electronics intelligence; communications intelligence; measurements intelligence; electromagnetic environmental effects; radar system performance modeling and simulation; advanced signal and array processing; sensor fusion; and antenna technology. Furthermore, SEAL cultivates advanced signal and data processing methods for acoustic sensors as well as multisensor intelligence exploitation architectures and algorithms covering all wavebands.

“We provide a range of systems engineering, software development and hardware-prototyping skills and services,” Belcher says.

The laboratory is a university-affiliated research center as chartered by the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics. As such, the lab is designated as having a set of core competencies important to the Defense Department. As part of the charter, the lab must provide customers with full intellectual property rights. “In exchange for our contracting arrangements, we’re obligated to make those competencies available to [the Defense Department] and its contractors,” Belcher offers. “That helps us with technology transition as well as with what we sometimes call the practical arts, as opposed to pure research.”

It is a good time to be in the prototyping business because the Defense Department’s third offset strategy stresses innovation to provide a technological advantage over adversaries. “The last five years have been very good for the prototyping business. There’s a great deal of prototyping for folks like us now,” Belcher reports.

The lab can have three to six major prototyping efforts underway at any given time. “The largest project in my lab now will probably top out at about $100 million,” Belcher says.

SEAL also specializes in improving existing systems, another Defense Department area of emphasis. “The third offset strategy has been a strong driver of prototyping at the labs ... not just building new things, but taking old things and integrating them and lashing them up in novel ways. That’s an area that we put a lot of effort into,” he says. “We actually have a very aggressive project right now where we’re taking military radars that were built for a totally different purpose and integrating them and networking them to do a very novel application function.”

The work can include getting systems to provide data they were not initially designed to supply or to deliver the same data at higher resolutions. Belcher cites ground surveillance sensors as one example. “A lot of the ISR assets, particularly for ground surveillance, have Cold War legacies,” he says, adding that customers “want to take some of these same assets in some cases and look for insurgents in urban areas.”

Lab personnel also design multifunctional systems. For example, military customers want to combine radar and communications or monostatic and bistatic radars in the same system. “We expect our platforms to do more missions now than we used to. By definition, any platform now is multimission,” Belcher elaborates.

Moreover, future adversaries likely will be adept at detecting and targeting radio frequency (RF) signals. “We’ve entered an era where emitting RF is not good for life span. It’s not good for platform survival. Just like we worry about the radar cross section, we worry about the RF signature, too. So, there’s more emphasis on minimizing your total RF signature and extracting more data from the environment,” Belcher asserts, adding that lab personnel are “developing some very novel architectures and techniques based on that RF digital convergence and aggressive multifunctional apertures.”

In some cases, they can integrate commercial technologies into innovative solutions. “We have a proverb in the business that everyone buys at Best Buy now. There’s a lot of commodity RF and digital technology out there,” he offers.

To help test the lab’s sensor payloads, researchers developed a flying test bed known as the GTRI Airborne Unmanned Sensor System (GAUSS). GAUSS gives the GTRI and its customers the ability to rapidly and cost-effectively develop and test new airborne payloads.

The GTRI team has created a modular design that allows the GAUSS platform to be reconfigured for a number of sensor types. Among the possibilities for evaluation are devices that use light detection and ranging technology and chemical-biological sensing technology.

More recently, SEAL researchers developed “the smallest active electronically scanned array that’s in active operation,” Belcher says. It is an X-band sensor and has about 600 megahertz of bandwidth. The array was created with internal research and development funding and is now ready to transition to the “application space.” The research team has demonstrated the ability to pull data “that’s probably higher resolution than folks would have anticipated” for such a small array, the director reveals.

SEAL was founded in the Vietnam era to focus on radar and electronic warfare and over time became the GTRI. The laboratory holds a place in history. It helped U.S. forces in Vietnam who, for the first time, faced Russian-made surface-to-air missiles—a major change in tactics and techniques.

“We built what was arguably the first foreign radar simulator during the Vietnam War era. That was when the United States first started building simulators, and we contributed to that community significantly,” Belcher says. “We’ve always been guys who went out and built things.”