Army Finds Communications Path

Concept improves connectivity between individual warfighters.

Networking capabilities that increase situational awareness are moving down the chain of command and eliminating bottlenecks in data sharing. Work underway on the Pathfinder advanced concept technology demonstration aims at integrating capabilities so that information gathered by unmanned ground vehicles, unmanned aerial vehicles and unattended ground sensors can be distributed within a mobile, self-forming, self-healing network. The system is designed for use by special operations and lightweight conventional forces in small team operations.

Pathfinder is sponsored by the U.S. Special Operations Command, MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, and the Urban Technology Office, U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center–Natick, Natick, Massachusetts. The Pathfinder team is not developing new tools but rather is taking proven capabilities and integrating them. Mature manportable commercial off-the-shelf and government off-the-shelf equipment will provide warfighters in the field with sensor data, surveillance information and targeting capabilities. The information will be displayed on both ruggedized laptop computers and handheld devices. Work on the project, which began in October 2002, will culminate next month. Then the technologies will move into an extended user evaluation through September 2006.

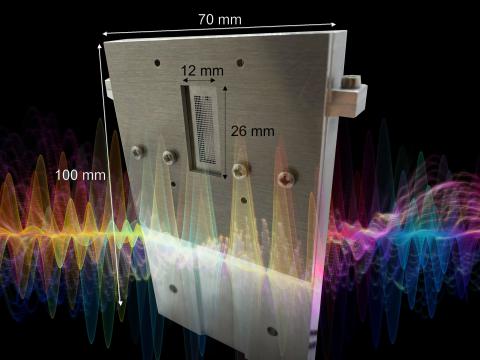

Adrien Robenhymer, electrical engineer, Pathfinder, U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center–Natick, explains that the backbone of the system is a network created by setting up nodes called BreadCrumbs and SuperCrumbs. Rajant Corporation, Wayne, Pennsylvania, developed the equipment to help firefighters find their way out of smoke-filled buildings. Several of either of the nodes, which are each smaller than a breadbox, can be placed in different locations to create an ad hoc meshed self-healing network. The SuperCrumb is being transitioned into use in the 3rd Infantry Division through a rapid fielding initiative.

The BreadCrumb network nodes can transmit data up to three miles; the SuperCrumb extends that range to between six miles and nine miles. Both require line-of-sight positioning so they work well in areas such as airfields, Robenhymer relates.

Over this network, soldiers can communicate through voice over Internet protocol, share video captured by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and obtain global positioning system coordinates, for example. If one node is destroyed or communications are jammed, the others seek another node to communicate with automatically, keeping the network in tact. In addition to transmitting information among each other, the nodes provide the client service channel.

A commercial system developed by BAE Systems is providing the sensing element of the Pathfinder demonstration. To alert troops about an approaching adversary, sensors hardwired into radios are hand placed in various locations up to three miles from a mission’s objective location. The sensors are approximately the size of two hockey pucks and monitor seismic, acoustic or magnetic changes. When they detect anomalous activity, the information is relayed through the network to the soldiers’ ruggedized handheld devices or laptop computers. The commander simultaneously receives the information, enabling him to react to an intrusion faster than when traditional warning methods are used.

Today’s capabilities can provide basic information to the warfighter, Robenhymer relates, such as when an object has passed by a light beam or when a heavy vehicle has traveled near a seismic sensor. However, acoustic sensors in the future may be able to detect the languages spoken as people pass by them. Advances in processing capabilities also could lead to the ability to identify and relay extremely specific information about a vehicle, including the type of tank and the country that owns it, for example.

Adam Fields, senior engineer, Pathfinder, U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center–Natick, notes that identifying vehicles with this degree of specificity will require an extensive database, but the capability would be very beneficial and the database could be developed. The process would be similar to the database development work the U.S. Navy submarine force conducted to categorize different sounds in the ocean. This directory now helps submarine crews not only to distinguish between live creatures and undersea vehicles but also to differentiate species of whales based solely on the sounds they generate.

Developing a vehicle database is not part of the Pathfinder project, Fields emphasizes, and will require a lot of time and money. But he is confident that researchers will undertake the work and that the capability will be available in the future.

In the meantime, however, combining information from different types of sensors provides warfighters engaged in operations with a much better picture of their surroundings. “When something is moving toward your position, is it large and heavy? With only a light beam, the vehicle could be a tank or a bicycle passing by. But with acoustic and seismic sensors, you know it’s heavier than a bicycle,” Fields relates.

Pathfinder engineers are exploring other ways to use the networking capability. Building on its experience with developing systems for military operations on urban terrain, the team is examining how to incorporate targeting technologies into robots. By integrating the special operations forces’ laser-aiming module into a robot, troops could approach a target and send a coded laser that would guide smart munitions to a target while the troops remain at a safe distance. Line-of-sight issues still need to be resolved for this part of the demonstration. “This is a way off, but we are taking the first steps,” Fields relates.

Pathfinder’s reach also extends into the skies. According to Fields, one of the project’s biggest success stories is the Raven UAV, manufactured by AeroVironment Incorporated, Monrovia, California. Work on the micro aircraft began before September 11, 2001; however, it accelerated after the terrorist attacks when the Army issued an urgent-need statement for more of the aircraft to use in operations in Afghanistan.

A derivative of the Army’s larger but still manportable Pointer UAV, the Raven weighs 4 pounds and has a wingspan of 4 feet. Unlike the U.S. Marine Corps’ Dragon Eye, which must be launched using a slingshot, the Raven is launched by tossing it like a football, and it lands by auto-piloting to a near hover then dropping to the ground. Fields relates that the Army’s UAV features the smallest infrared cameras and a military rather than commercial global positioning system to prevent interference from jamming.

Ravens can be flown in a number of ways. Soldiers can program waypoints into the UAV so it flies a mission autonomously, or ground pilots can direct a flight using a joystick. In addition, the Raven can be programmed to fly to a specific location and remain at a designated altitude while a ground user directs only the onboard cameras to capture specific images. Members of the company or battalion can view the information the UAVs obtain over the network using a computer interface that features a moving map display.

At this time, the Pathfinder team has been demonstrating the ability to fly four Ravens simultaneously over one area because only four radio frequency channels are available. However, once the communications links to the UAVs are digitized, each aircraft could have its own Internet protocol address so the number of flying aircraft could increase.

Information-sharing capabilities will be driven by available bandwidth. Hundreds of Ravens have been fielded in operations to date, and Fields says he expected that, as a result of the experiences in Afghanistan, 1,000 Ravens would be supporting operations by the end of last year.

Once all of this battlefield information is gathered and moves over the network, soldiers need to be able to view it. To provide the flexibility warfighters requested, the Pathfinder team has been working with two types of displays. The Panasonic Toughbook, a hardened laptop, offers a large display field so soldiers can view more detailed information such as the moving map display. The Special Operations Command is developing a handheld device called the Tacticomp that features an internal networking capability and provides the functionality of a number of pieces of gear, including a radio, global positioning system receiver and laser rangefinder.

To test the integration of the various components of the system, Pathfinder has been demonstrated during several limited objective experiments. The system also was part of millennium challenge 2002 where the team assessed the Raven’s ability to transmit images. Reconnaissance images were gathered then saved and displayed on a Web page where all participants could view them.

Although the Pathfinder team intended to train warfighters with the equipment long before sending it into the field, the high tempo of current operations has precluded this plan. However, in addition to the experiments, 10 members of the Pathfinder team were embedded with Rangers for more than a week last spring during a U.S. Air Force combat control training exercise at Fort Benning, Georgia. Two- and three-man teams carried 63 pounds of Pathfinder equipment into real-life conditions during the exercise.

“It was a lot of work and an incredible experience. They do a lot, and it gave us a better idea of what they need and real-life conditions. For example, we found that they need light to be able to see the displays in the dark. We came out of it knowing that we have to find them better equipment,” Fields says.

Adding more weight and volume to warfighters’ already overloaded rucksacks is a primary concern at the U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center–Natick. However, Andrew Mawn, technology program manager for Pathfinder at the center, points out that if a tool is useful, soldiers will leave other items behind and carry it. Although the network nodes, sensors, UAVs, laptop computers and handheld devices increase the load, the benefits this equipment offers can shorten a mission and reduce the amount of other necessary supplies, Mawn notes.

“When they have to go out on a three-day mission, for example, soldiers have to carry all the equipment plus all the food, water, batteries and other supplies to support the soldiers for three days. If this equipment can shorten the time that’s required for that mission, they don’t have to carry all the support equipment, so this equipment is not additional weight.

“That is the true acceptance test. If you lay out all the equipment on the ground, the soldiers tell you what they are willing to carry because it is important to them, and they pick your equipment, then it’s a success,” he relates.

The engineers have faced two types of challenges during the past two years of work on the project. From a technical standpoint, Fields notes that they have had to solve problems of frequencies, antennas and terrain. In addition, Robenhymer points out that the team had to develop easy-to-use interfaces for the users because training time is at a premium. “It has to be high-technology in a low-technology package,” he explains. From an overall project standpoint, the team leaders concur that the high operational tempo for the military has made training a challenge as troops are rotated into operations.

Team members also agree the one key to Pathfinder’s success has been soldier input. Mawn emphasizes that user feedback is critical to any research and development effort because it ensures that the final product not only meets the needs in the field but also offers real value.

Fields allows that some of the Pathfinder capabilities already have moved into the field in a limited way. This is a good approach, he says, because the team can begin work on the next generation of capabilities with soldier input in mind.

As the project moves forward, the two challenges that will need to be addressed are bandwidth allocation and the encryption process, Fields notes. Although the system will continue to be fielded in limited quantities, these issues will need to be resolved before it can be fully fielded, and this will take some time, he adds.

Web Resources

U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center–Natick: www.natick.army.mil

U.S. Special Operations Command: www.socom.mil

1st Infantry Division: http://www.1id.army.mil/