Army Networking Technologies Change on the Fly

New capabilities mean new training challenges.

Satellite dishes are lined up for testing at Fort Lewis, Washington. The U.S. Army’s 51st Expeditionary Signal Battalion is training on new networking equipment before it ships out to Iraq later this year.

The U.S. Army is changing communications equipment faster than it can deploy forces equipped with that gear. The force benefits from improved networking capabilities, but this rapid technology insertion is changing the way communications battalions train and deploy.

Training is evolving as dynamically as the technology. Soldiers not only must learn new hardware and capabilities, they also must train to operate the gear under the new warfighting doctrines that it enables.

One Army communications battalion is combining training with technology shakeout well before it deploys to

Most of the gear is commercial off-the-shelf. It includes a commercial-based phone switch and a voice over Internet protocol (IP), or VoIP, capability that is projected out to the CPNs. The goal of this new technology is for the ESB to field a more versatile system that provides connectivity at greater distances well beyond line of sight.

What sets an ESB apart from other Army signal units is that it is not attached to a single division. The 51st can serve as a corps asset augmenting divisions that need more signal support. It is not dedicated to supporting one particular element as would a brigade combat team.

Lt. Col. Paul Fredenburgh,

One ESB replaces the capability of two Mobile Subscriber Equipment (MSE) battalions. The ESB can support 30 operational command posts from battalion level up. It also can support brigade combat teams, combat arms maneuver battalions, corps-level entities and joint task force-level entities, the colonel explains. “We can plug any hole, bolster any communications at the lower level and provide all the way up to joint task force headquarters.”

He continues that every single node in the network is satellite-based. It is not tied to any terrestrial network. So, it does not matter where a commander is or needs to go. As long as the node can access a satellite, the commander will have connectivity.

Instead of the Army’s traditional five-year acquisition cycle, the ESB receives its gear in half that period, Col. Fredenburgh reports. It conducted confidence tests on the equipment in March.

The 51st is the fifth ESB to field the new equipment in the Army. Three other ESBs with the new gear are in

When the 51st replaces another ESB in

The 51st’s equipment is so new that it has not been field tested yet, Col. Fredenburgh points out. The ESB is adding lessons learned from network operations in

The battalion began turning in its old equipment about one year ago. Some gear, such as line-of-sight shelters, was submitted for retrofitting. Other gear was replaced by new equipment for ongoing missions. The JNNs and CPNs arrived late last year.

The equipment is being set up several months before the battalion will go to

Training for the soldiers involves more than learning new technology. Col. Fredenburgh points out that these communicators also must be in tune with the maneuver concept of operations. They must look to the future so that they can anticipate providing necessary bandwidth and capabilities.

“We’re not just training to go over to

|

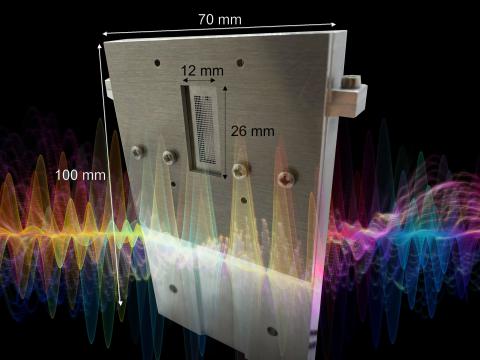

| Single Shelter Switch (SSS) racks undergo testing at Fort Lewis. Soldiers are finding it easier to learn how to set up and operate the new commercially based gear. |

Although much of the gear is commercial, most soldiers require training from the ground up, Maj. Shipley says. Constantly changing technology requires refresher training at the very least, even for soldiers fresh from the

When the deployment to

Much of the equipment already has been deployed among other units in

And some contractors will be with them, depending on their equipment areas of specialization. Most of their duties will involve troubleshooting rather than actually running the systems. Some gear is under warranty, and soldiers are not allowed to tinker with that equipment if problems arise. So, the on-site civilian experts in

Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Crews,

The improvements in technology include greater bandwidth, which allows communicators to send more data down a single stream. Instead of running one cable for each telephone in a shelter, a single line can carry multiphone traffic into a switch. The majority of telephony links are VoIP, but the system can accommodate four-wire digital nonsecure voice terminals and two-wire telephones through a PBX switch in bigger shelters. Individual units rely on VoIP links. All commands at battalion level—where the CPN is located—and above will be able to videoconference.

Col. Fredenburgh notes that one aspect of the new technology is that a network operations capability is being fielded down to the company level. If necessary, a company could deploy as its own entity and still conduct the network operations required of its network sector. This pushes leadership and network responsibility down to a much lower level, he points out, and it is making forces smaller and more modular in their ability to deploy.

Maj. John Taitano,

The ESB has faced two major challenges, Col. Fredenburgh says. One was logistical: transforming all of the old equipment and getting vehicles and generators in order has been very time-consuming, he states. The other challenge has been the training and the refinement of the doctrinal piece—specifically, where the ESB fits into network protection and network operations. This includes determining where the ESB lashes up with the G-6s that control the division networks, along with the tie-in with the tactical theater signal brigade that provides network operations support centers.

Maj. Chad Duhe,

Maj. Taitano offers that his biggest challenge will be network operations. The old MSE world had well-known standards, but now operators must learn new ways of conducting network operations. They also must learn the tools of managing this new type of network.

“The soldiers always will be able to put in systems—to put in the CPN, to put in the JNN,” he says. “That’s the easy part. The hard part is tying it all together and managing it at our level.”

Maj. Duhe sees consistency in positives and negatives. “The worst thing that’s happened is that we might have to work through some initial bumps in the road to get some things working,” he says. “The greatest thing that’s happened is that we might have to work through some initial bumps in the road to get some things working.”

He continues that the soldiers’ mindset must be “jack of all trades.” They must take the form of “the pentathlete model,” and they must be flexible enough to absorb new concepts and take on new challenges. “The most successful units will be the ones that respond quickest and most effectively to customer needs,” the major posits.

“In this transition, we’ve changed a lot of our equipment, and we’re going to the best equipment you can find anywhere in the world,” declares Sgt. Curtiss Kluczinske,

Web Resource

Commercial Gear Defines Army Communications Training U.S. Army communicators training on new networking equipment literally are rewriting the schoolbooks as they prepare to replace legacy systems with new gear based largely on commercial technologies. Soldiers with the 51st Expeditionary Signal Battalion (ESB) at Fort Lewis, Washington, are blending knowledge of old technologies with familiar commercial systems as they complete an extensive training regiment before being deployed to Iraq. The focal point is the set of new technologies that the communicators will use to link diverse units in The JNN is a reliable system that largely runs itself, says Pfc. Marcus Egan,

Recent JNN training lasted three months for these soldiers. Every day, 22 trainees would start up a new network to learn ways of setting up the gear and incorporating new equipment. Spc. Gillespie notes that familiarity with old equipment was an advantage in this case, especially with regard to troubleshooting. People who were knowledgeable about the new commercial equipment were able to catch on quickly. Spc. Gillespie relates that some of the JNN instructors had been deployed to About a dozen different versions of the JNN have been introduced into the Army, with each version benefiting from upgrades based on lessons learned and technology advances. In some iterations, elements that have not been used frequently have been replaced by components that offered more important capabilities. Pfc. Egan previously deployed to One problem with the JNN is its long startup time. Pfc. Egan relates that it can take longer for the system to spool up and for users to have it up and running. Once you’re in, he says, you’re in, and use is pretty easy. With MSE, even after setup there were too many chances for problems to arise. This ease of operation translates into a smaller manpower footprint, notes Spc. Johanna Rodriguez, As new commercial capabilities become available, they will be incorporated into the JNN, Spc. Gillespie offers. The coming capabilities may feature more nonsecure/secret Internet protocol router network (NIPRNET/SIPRNET) drops, he suggests. Increased bandwidth may be next. The SSS is the battalion’s large switch. It can act as a hub to hook up JNN, fiber, satellite and even troposcatter communications. It largely provides communications to echelons above corps, which requires support to many customers employing a host of different media—data, voice and video, for example. Sgt. Rickey Thomas, The improvement over the older MSE gear is substantial, recounts Spc. Robert V. Gomez, Mobility is one key capability that the SSS will provide to the force in the field. Spc. Gomez says that soldiers are looking into wireless communications within the SSS. A wireless domain extends the logistical range of its links. Spc. Jason Jacobs, Soldiers in the field are not limited to line of sight in their communications connectivity. They will be able to range as far away as necessary while remaining connected to the same switch. They need not change switches if they change areas of responsibility, because they can maintain connectivity via satellite. This should speed up the flow of battle and mobility. The SSS also allows for greater usage of computer networks, Sgt. Thomas indicates. Individual warfighters can use chat functions to communicate with others—potentially an entire platoon on computers being able to send information up to headquarters. Training on the SSS takes about 10 weeks, Spc. Jacobs adds. All told, the full course on the SSS that the communicators took ran about six months. This comprised hands-on training complemented by classroom instruction. Spc. Michael Melton, The class did run into some unexpected hurdles, according to Spc. Gomez. For example, when one piece of equipment did not work correctly, soldiers determined that it originally had been configured incorrectly by both the civilians and the trainees. After a full day of troubleshooting, the piece of equipment was pulled out and completely re-set, after which it worked perfectly. The gear had been named in its initial configuration, which gummed the process. Sgt. Thomas relates that the next-generation switch is in the works, and the SSS should be able to be upgraded to that configuration to operate faster and to support more bandwidth. This upgrade can be achieved simply by replacing one piece of equipment in the shelter and adding new software. The CPN replaces the traditional node center. It effectively serves as a network endpoint, observes Spc. Clinton Peterson, It suffers less from interference, is simpler and is much easier to set up, notes Spc. Nicole Reese, This new CPN also allows the subscriber to have more command and control over the actual network, explains Sgt. Curtiss Kluczinske, The soldiers effectively are getting a mobile office, explains Benjamin F. Hutchinson Jr., a contractor fielding site manager for Program Manager Warfighter Information Network–Tactical (WIN-T). It has a much greater reach-back capability than MSE. The new gear is compatible with legacy MSE equipment, which can be run off of this system. “It will take a smarter, more skilled soldier now to operate this equipment, but we gain a lot more over the old technology,” he says. In terms of training, most of the people who have worked on this equipment were exposed to it in the private sector, Sgt. Kluczinske points out. The training for CPN reflects this, as CPN operators largely do not need a top-to-bottom instruction session. The system’s STTs are highly mobile and are towable by a high mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicle (HMMWV). They feature time division multiple access (TDMA) modems and offer higher bandwidth capabilities. All of the equipment is commercial, and it is equipped with a global positioning system (GPS), which enables a relatively easy 30-minute setup. Operators merely level the terminal, power it up in an arranged sequence and then program its parameters. Operators can interface directly through a conventional laptop computer. Spc. Cedric S. Nicholson, Its graphical user interface allows virtually anyone to operate it, observes Spc. Nicholson relates that training lasted roughly one week, but it took little more than a day to instruct someone on basic setup and installation. Troubleshooting takes longer to learn depending on the soldier’s experience on other gear. The first units were delivered to the battalion last autumn. “If you know how to work a laptop and know how to go into a program and [search for] satellites at a specific location, the system will go straight there by itself,” explains Sgt. Artist T. Young, One surprise came about when programming the TDMA modem, allows Spc. Patrick Ramos, The STT does not lend itself to appliqué upgrades. Sgt. Young points out that adding a new capability would require replacing an old one. Engineers could increase capabilities by carrying out a two-for-one replacement. Troubleshooting also would be easier if the STTs’ back panels were more accessible, he adds. The terminal is one of the commercial systems with a warranty. Accordingly, the soldiers cannot perform detailed repairs. They must return a broken terminal to the contractor. This inhibits a soldier’s role as satellite operator/maintainer, Sgt. Young allows. |