Digitization Brings Quantum Growth in Geospatial Products

|

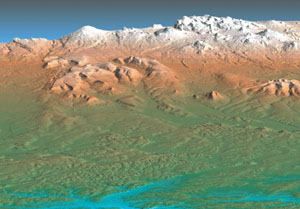

| A National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) image of Russia’s volcanically active Kamchatka peninsula displays terrain elevation in different colors. This image was enabled by data collected by the shuttle radar topography mission (SRTM) in 2000. Growth in both the volume of data collected and its user applications is increasing the demands placed on the agency. |

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, fresh from assuming a new name less than a year ago, is striving to meet several self-imposed goals to address shortcomings and to confront the challenges of 21st century network-centric warfare. On its to-do list are converting fully to digital products and services; pursuing an e-business model; and transforming its architecture. It also seeks to pursue advanced forms of geospatial intelligence, including electromagnetic spectrum, and to mature the ability to capitalize on airborne collection. And, the agency’s leadership foresees a need for two new headquarters facilities to deal with burgeoning responsibilities and an increased terror threat.

Meeting the agency’s operational needs will require establishing a new approach to mixing human expertise with computational potential. As advanced technologies impel the military’s force transformation, the agency must increase the type of services it provides as well as the quantity of information it disseminates. Ultimately, the agency must be able to produce geospatial information system (GIS) data products for virtually any spot on the Earth at a moment’s notice.

“When you think about it, everything and everybody has to be somewhere,” warrants agency director Lt. Gen. James R. Clapper Jr., USAF (Ret.). “That truism is the business we are in.”

Gen. Clapper offers that the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s (NGA’s) new name represents less a change of direction and more an affirmation of missions that originally were envisioned by the founders of the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) in 1996. Subsequent studies, including the congressionally mandated NIMA Commission report, reinforced the importance of converging, synthesizing and melding the previously separate pursuits of mapping, charting and geodesy with imagery and its intelligence and analysis. When this synergy occurs, the results are greater than the sum of the parts, the general maintains.

People making decisions tend to think graphically, the general continues. Being able to generate a three-dimensional image of a setting provides a planner with many options. A special operations activity, for example, can require considerable detail in items such as the size and construct of doorways. Pilots preparing for ground attack missions can benefit from visual knowledge about the materials on roofs along the approach path to the target.

“When you can describe and depict visually and graphically the Earth—either in its natural or manmade condition, in terms of a setting or a scene that may have some national security import—it is a very powerful and compelling item,” he says.

The general emphasizes that a major thrust of his agency is to convert to a digital format. “The nirvana vision here is to populate, in some detail, a very rich database with the layers of geospatial information and intelligence available to a user who could go in—just as you do on the Internet—and do customer self-service,” he declares. This user would be able to draw out whatever layer or set of layers is needed for a particular mission. This runs counter to the traditional hard-copy approach, although the military probably will always want some hard-copy products. Ultimately, the NGA will work toward reducing the amount of hard copy it produces.

This digitization also addresses the changing nature of the threat facing the Free World. Instead of one profound military threat, the United States and its allies face a global threat that can emerge almost anywhere. So, the NGA must be able to support military forces almost anywhere. The result is that the agency has been driven to provide more just-in-time support instead of keeping “the encyclopedias of the world stacked up on bookshelves,” the general relates.

Accordingly, the agency must have a very robust apparatus to accommodate the collection, processing, exploitation and dissemination of GIS intelligence to the customers. In the same way that military officials stress the importance of persistent surveillance, Gen. Clapper allows that he is trying to be the champion of persistent tasking, processing, exploitation and dissemination, or TPED. “You must have both,” he declares, “because once the material is collected and exploited, then it must facilitate or support the decision-making loop.” Instead of procuring and fielding a TPED infrastructure as an afterthought, the defense community must view it as a primary dimension of the GIS apparatus, he says.

The amount of geospatial information that the NGA will handle is increasing exponentially. Over time, the intelligence community will assume a better capability to conduct surveillance of any spot on the globe, albeit not a perfect form of persistent surveillance, he emphasizes. Also, the number of sources will be increasing dramatically. Elements such as the Future Imagery Architecture, commercial imagery, more unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and other sources of information will generate a huge volume of data, the general observes.

|

|

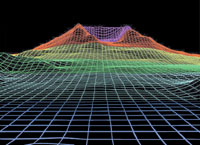

| Two images of Mt. St. Helens using SRTM data show the different forms in which the NGA can present geospatial imagery. At left is a shaded relief image where changes in elevation are presented in varying shades of gray. At right is a wire map image where elevation contours are represented by grid lines. |

With this huge mass of data growing exponentially, the agency would require similar increases in the number of analysts and other support personnel to handle all of the information. However, Gen. Clapper states that the agency is looking at automation to relieve the burden on the geospatial analyst. Tools such as automatic target recognition would free personnel to deal with the complex and ambiguous tasks that still must be performed by humans.

Imagery analysis is an art, not a science, he emphasizes. Many aspects can be automated to facilitate the process for analysts, particularly target recognition, database building and metadata tagging. However, the information collected and processed by the NGA may include nuanced signatures and subtle changes that require an understanding of the context in which an image is viewed. In the end, no computer can substitute for the human eye or the human mind.

The general emphasizes that the agency’s automation thrust will not be a trivial task. The agency must be more astute about “throughput management,” he warrants. It will not be able to look at every bit of geospatial intelligence, but the agency will have to archive it as it is doing with theater-collected imagery from sources such as Global Hawk and Predator. For the first time, the agency has a library where it can research this collected data instead of discarding it when the operation is over. The need for archived material will increase with the amount of data collected, but archiving also will be necessary to track the evolution of a development over time.

The agency is making a multibillion-dollar infrastructure investment to accommodate the upcoming data tsunami. The ground infrastructure must be in place when new systems, such as the next-generation of national technical means, come online so that it can accommodate the collected data, the general points out. Communications is a key element of that infrastructure upgrade.

Personnel issues are another matter. The agency cannot hope to increase its number of in-house analysts commensurate with the growth in data. So, it is turning to private industry contractors to handle some of its requirements.

Gen. Clapper notes that fiscal year 2003 represented the first year in which the number of contractor full-time equivalents exceeded that of the NGA’s total government work force. That trend is continuing, so an even greater percentage of the agency’s work force will be contractors. Among analysts, the agency increasingly is contracting with retirees. These annuitants serve as mentors as well as technical experts, and the younger NGA employees can reap the benefits of these mentors’ decades of experience. So, even if the analytic work force declines, the agency has a broad range of expertise to tap.

Industry will play a key role in helping the NGA achieve its goals. The agency’s entire modernization program under GeoScout is charged to a Lockheed Martin-led contractor team, the general relates. The agency is looking to industry for innovation to change its entire infrastructure as it modernizes. He adds that he hopes commercial imagery will become “very viable and internationally dominant.”

Foremost on the private-sector technology wish list is the ability to correlate, move and portray data, Gen. Clapper states. Technologies that provide processing and computational capabilities for volumes of multispectral or hyperspectral data also are needed.

The ability to manage data lies at the heart of the NGA’s activities in the digital age. The agency also must capitalize on what has been learned about the Internet and the power that it brings to the customer. “We’re very interested in bringing in new and spiffy concepts, software technology that we can hopefully insert quickly as we modernize,” he says.

The ongoing force transformation sweeping the military community has intensified NGA’s activities, the general suggests. One theme common to all of these transformation efforts is a great premium placed on situational awareness, precision, timeliness and being nimble. In turn, this places a great premium on the generation of geospatial intelligence that characterizes NGA activity. This trend is likely to continue, possibly to an even greater degree, as the military shifts to smaller weapons that require an increased degree of rapid precision targeting.

Gen. Clapper notes that a significant requirement underpinning the U.S. Army’s Future Combat Systems (FCS) is the need for “very rich foundation data.” This is necessary for the FCS to operate anywhere on the Earth, he notes. The U.S. Navy has formed a partnership with the NGA to achieve its digital bridge. This effort will eliminate the traditional picture of quartermasters carrying rolls of paper maps on the bridge of a ship.

The recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrated the utility of digitized GIS products in combat. “We do wars in the chatroom now,” Gen. Clapper observes. The free flow of imagery information significantly affected command and control activities.

One of the key enablers of that free flow of GIS was the presence of NGA personnel embedded with the agency’s customers, the general notes. The agency had many people deployed to the area of operations prior to and during the Iraq War, and it still maintains a presence in theater. This proved exceptionally useful to both the agency and its customers as the GIS dataflow increased. “It is a very powerful thing when you have the expertise from this agency—or any other, for that matter—in the customers’ footprints, enduring the same hazards and privations, just like the customer they are supporting,” he emphasizes. “That has a way of focusing [attention] on just exactly what the customer needs.”

This on-site expertise proved useful in several ways. A customer may not understand fully just what the NGA can do to meet its requirements. Gen. Clapper relates that he has seen many examples of an embedded agency employee understanding a commander’s needs and then reaching back to the NGA in the United States to generate products that the commander might not have expected. Again, the thrust to digitization will help facilitate that capability.

The ongoing transformation also is changing the way that the NGA provides support to its customers. Across the breadth of the intelligence community, the traditional model of delivering a product to the customer is giving way to the customer choosing and defining the product. Not only will this help ensure that the NGA customer receives a better-tailored product, it also will reduce the burden on the agency, the general offers. This will increase the pressure on the agency to continue to bring technological innovations into its system to keep abreast of customer needs, he adds.

Bandwidth availability remains a challenge. Gen. Clapper anticipates that the agency will improve its capabilities to compress imagery and to sustain its quality. Increased bandwidth through additional satellite capacity will help move imagery to the customer. The Global Information Grid–Bandwidth Expansion (GIG-BE) is a big part of the NGA’s future architecture, the general notes.

One way of reducing bandwidth demand is to allocate UAVs to battalion commanders. With this degree of autonomy, these commanders can look over the next hill without having to request imagery from a command center in the United States.

On the home front, the NGA wants to consolidate its facilities into two new campuses: one in the national capital region and the other in Missouri where the agency currently has 30 percent of its capabilities. The existing headquarters facility in Bethesda, Maryland, is 60 years old and does not meet current infrastructure requirements or even force protection standards. To replace the current collection of government and leased facilities, Gen. Clapper would like a headquarters that is “modern and designed for the purpose.” Having two modernized campuses could help ensure continuity of operations, he adds.

Homeland Security Offers New Missions and Limitations The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) has been supporting homeland security activities through the products it has supplied to the military. Originally designed for disaster relief, these capabilities have been overlaid into a domestic homeland security context. Ultimately, the information and intelligence requirements to support homeland security are “every bit as exquisite and voracious” as they are for the military, declares NGA director Lt. Gen. James R. Clapper Jr., USAF (Ret.). An NGA team at the Department of Homeland Security helps provide support to that department. The agency supported special events such as the recent G-8 conference in Georgia and President Ronald Reagan’s funeral by providing the common operating picture for the command center set up for each event. This provides a geospatial common denominator that ensures that all participating government organizations see the same picture. Gen. Clapper explains that the NGA cannot provide direct assistance to state and local authorities. The agency can support these organizations only through a lead federal agency, which usually is the Department of Homeland Security. The use of surveillance resources in a domestic context requires the use of different approval mechanisms. The general guideline is that imaging a collective area—several city blocks, for example—requires a rigorous but routine approval process. Imaging a dwelling or another type of single building requires a search warrant. However, the agency can use commercial airborne platforms to perform those tasks. These platforms may not be suitable for overseas deployment, but because the United States is not a denied area, the agency can exploit those products. |

Comments