Marines Exercise New Warfighting Strategy

To address a changing mission amid broader challenges, the U.S. Marines are implementing the service’s future warfighting strategy this year through training, war gaming and experimentation. The strategy calls for forces to be dispersed over wide areas and will require technologies that enhance warfighters’ effectiveness over greater distances.

The new strategy, referred to as Expeditionary Force 21, was expected to be finalized in March. It is designed to transition the corps from landlocked desert warfighting back to its maritime-based roots. “This is really going to change how the Marine Corps does business—not what we do as Marines—just how we do it. It really focuses on being forward deployed, with a forward presence globally, with ready forces and a focus on crisis response,” says Brig. Gen. Kevin Killea, USMC, director of the Futures Directorate, commander, Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, and vice chief of naval research.

Since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the Marines have been organized for major combat operations in landlocked desert areas. The requirements for smaller crisis response operations would flow down from the higher-level warfighting requirements, Gen. Killea explains. “We’re flipping that on its head and doing it from the ground up by emphasizing forward presence globally, having smaller forces out there. And then when needed, we can aggregate those units in an area of crisis that would demand larger and larger forces,” he says.

The strategy document essentially is complete and “looks great on paper,” the general says, but it will continue to be tweaked on an annual basis, largely through lessons learned during exercises and experiments. This began earlier this year with a war game called Expeditionary Warrior 14. “We’re implementing the strategy in many ways, not only education-wise throughout the force but also through war gaming, exercises and even some live force experimentation,” Gen. Killea reveals.

Expeditionary Warrior 14 was conducted before the strategy finished the final rounds of approval. The Marines are able to quickly begin implementing the strategy because much of it has already been laid out in “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower,” an umbrella maritime document crafted by the Navy, Marines and Coast Guard. “The general principles and themes and tenets don’t change once they’re approved by higher strategy and by the service chiefs. It’s really the implementation plan and how you’re going to do it ... that takes the most time,” Gen. Killea adds. “We’ve got all the services involved. The Joint Staff’s involved. We’ve even got coalition partners taking a look at how we’re going to fight in the future.”

The tenets of the new strategy also will be tested during an Advanced Warfighting Experiment this summer, which will be conducted in conjunction with the Rim of the Pacific exercise, commonly referred to as RIMPAC, and during the multinational Bold Alligator exercise being conducted this fall on the East Coast. “We’re using operating forces conducting a normal exercise to do some experimentation live-force-wise that reflect the tenets of Expeditionary Force 21,” Gen. Killea says.

The new strategy offers significant challenges that Gen. Killea refers to as the “tyranny of distance.” He illustrates the concept with a hypothetical situation. “Look at the continent of Africa and just pick somewhere in north central or south central Africa, and then just go up to the Mediterranean and look at the distance that a response force would have to travel. If it’s a dispersed force, it doesn’t take you long to think about what the communications challenges would be, the command and control challenges of dealing with forces like that,” he suggests.

The 21st century strategy also will push small-unit leaders to take on greater responsibilities, requiring improved command, control and communications. “When you disperse forces, and you create a tyranny of distance, reliable networked, beyond-line-of-sight communications becomes paramount. That’s one of the main areas we’re focusing on right now,” Gen. Killea reports.

That beyond-line-of-sight capability is “very close,” the general predicts. “When we are focusing on forward presence and more dispersed operations, that is something that we really have to get right,” he declares.

Tyrannical distances present other challenges to warfighters—and, therefore, to the science and technology community. He cites ship-to-shore connectors and energy usage as two important areas needing improvement.

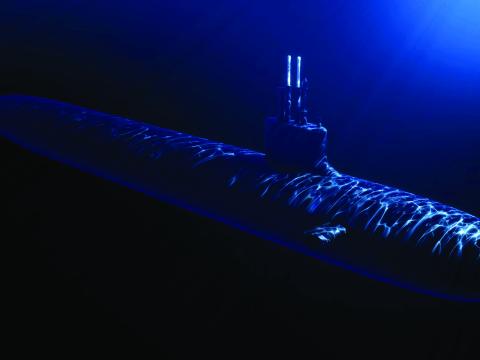

The Marines primarily use two types of connectors: the Landing Craft Utility (LCU) and the Landing Craft Air Cushioned (LCAC). The LCU carries a lot of materiel and people but moves at only about 8 knots per hour, the general estimates. It operates from about eight or 10 miles off the coast. The LCAC, on the other hand, is faster and operates farther out, but it doesn’t carry as much, he explains. “We’re beginning to explore connectors where we’re going to get the best of both worlds, connectors that can do, say, 20 knots and give us more ability to use the sea as a maneuver space but can carry as much as the LCU. The rapid buildup of forces ashore is going to require those connectors,” he states. “If you think about the future security environment, there are advanced threat systems throughout the world that will compel us to be farther and farther out at sea,” Gen. Killea states.

The second major area needing improvement is expeditionary energy, specifically fuel and battery usage. The Marines released an expeditionary energy strategy in 2011 that calls for the service to cut in half the fuel usage per Marine by 2025. Gen. Killea says the service is exploring fuel cells, solar technologies and other alternatives. “The Office of Naval Research is doing some really great work in battery technology, and I think they’re close to some breakthroughs there,” he says.

He also anticipates breakthroughs in semi-autonomous and autonomous technologies that will allow unmanned systems to play a greater role on the future battlefield, once capabilities are refined and limitations understood. He stresses, however, that it is “yet to be determined” whether robots will be armed. “Initially the advances in autonomy that we’re seeing will help us out first in the intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance realm with autonomous unmanned aviation assets and also ground assets with regard to sensors and being able to provide situational awareness. That’s going to be the first step before you see semi-autonomous robots that are kinetic,” Gen. Killea predicts. “The autonomous and semi-autonomous capability of robotics is on the edge right now, and it’s going to break through in the next five to 10 years.”

The Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory is evaluating a number of unmanned systems, including the mule-like Legged Squad Support System, which is capable of carrying up to 400 pounds of gear and traversing terrain too tough for tracked or wheeled vehicles. The system will likely be evaluated in a jungle environment for the first time this summer, the general says.

The Warfighting Laboratory also is working with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency on the Tactically Exploited Reconnaissance Node (TERN), a medium-altitude long-endurance unmanned aircraft that will use smaller ships as mobile launch and recovery sites. TERN is needed because effective 21st-century warfare requires the ability to conduct airborne intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and to strike mobile targets anywhere, around the clock, according to the Defense Department. Current technologies, however, have their limitations. The TERN program seeks to combine the strengths of both land- and sea-based approaches to supporting airborne assets.

Gen. Killea also is in charge of the Futures Directorate, which was created within the past year by combining a number of existing organizations under one roof. “The reason we put the Futures Directorate together is to streamline efforts, to take that future look and ensure that it’s informing the 10-year objective plan of the force development vision. Anytime you throw change at an organization like that, it takes a little time for it to settle in, but we’ve been at it for several months, and it’s all coming together,” he says.

Comment

Great article!

Great article!

Comments