Air Force Wants Its Innovation Gap Back

The race is on for one U.S. Air Force directorate to restore the technological edge the service has had over other nations’ militaries. It is funding research into propulsion, power and air vehicles that could produce next-generation scramjet engines, alternative fuels and hypersonic vehicles, to name a few.

High on the priority list at the Air Force Research Laboratory’s (AFRL’s) Aerospace Systems Directorate is the Hydrocarbon Boost Technology Demonstrator, or HBTD, a national program to improve rocket booster technology for the U.S. Defense Department and reduce dependence on foreign high-lift booster systems—in particular, Russian technology. “The Air Force has made it clear that recapitalization and maintaining readiness of our nuclear deterrence force is our No. 1 priority, and HBTD can aid in that requirement, so it’s a very high priority program,” says Col. Joel Luker, USAF, the directorate’s acting director.

“Back in the mid-1990s, when the relationship between the United States and Russia was looking a lot better than it is now, we made the strategic decision … to start using their booster systems for some of our high-lift requirements to get things into space,” Col. Luker adds. “As the relationship between the United States and Russia has become a little bit more filled with tension recently, we want to make sure that we have an organic capability and that we’re not completely dependent upon the Russian booster systems.”

Under the direction of the AFRL, Aerojet Rocketdyne is designing, developing and testing the HBTD engine. It is expected to generate 250,000 pounds of thrust using liquid oxygen and liquid kerosene. Additionally, engineers have designed it as a reusable engine system, able to power up to 100 flights. Officials are looking to finish the program by early 2020, Col. Luker says.

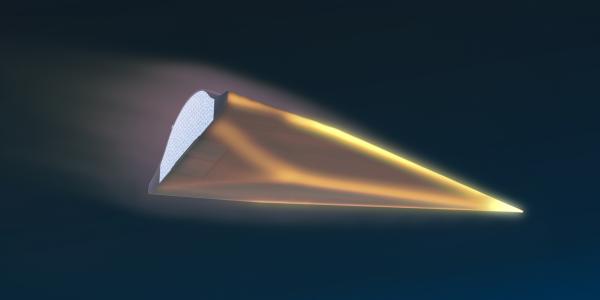

For some of its projects, the AFRL has teamed with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop air-to-ground munitions. One project is the Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC), which would allow the military to carry out operations faster and from longer ranges. The HAWC program would bring to the U.S. military’s arsenal an air-launched hypersonic cruise missile and address three critical technology challenges: air vehicle feasibility, effectiveness and affordability, according to DARPA. The program also could produce reusable hypersonic air platforms for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions and space access.

A second AFRL-DARPA partnership involves work on the Tactical Boost Glide (TBG) program to develop technologies for future air-launched, tactical-range hypersonic boost glide systems. In a boost glide system, a rocket accelerates its payload at high speeds, then detaches from the payload, which then just glides to its target.

Improvements in the hypersonic area by other nations spurred creation of the high-speed munitions programs, Col. Luker says. “In general, I’ll say threat systems are becoming more advanced. The overall strategy from some of our potential competitors is to push us further offshore or away from the targets we want to get to. They’re also developing systems that are more mobile, which makes [them] more difficult to target,” he says.

Development of hypersonic systems, which would travel greater than five times the speed of sound, would allow the United States to operate from farther distances—outside of known kill zones—and still deliver munitions in time to counter mobile targets.

Col. Luker’s use of the term “potential competitor” is a calculated one: “I’m being very careful about my choice of words there. Right now, we don’t have any near-peer adversaries.” Pundits often cite Russia and China as nations posing some of the greatest threats against the United States. “We’re not at war with them,” he continues. “We have an existing relationship and world order that’s been in place since World War II … that has been very effective. I wouldn’t call them adversaries. In fact, there are a lot of areas where we cooperate and do things together. That’s why I use the term ‘potential competitor’.”

In addition to hypersonics, the directorate’s portfolio includes what officials call Low-Cost Attritable Aircraft Technology (LCAAT); an Air Force Life Cycle Management Center prototype system developed from major turbine engine research; and a demonstration of an autonomous aircraft teamed with a manned fighter, Col. Luker lists.

An extensive portfolio ensures that similar AFRL programs are developed in synchronization with each other to address the narrowing U.S. technological gap. “There are a lot of potential near-peer competitors who are catching up technologically,” states Col. Luker, who will lead the Air Force directorate until a civilian executive is selected in the spring. “The technological edge that the Air Force has had over our potential competitors is shrinking. Technology is starting to move faster.

“Some of our potential competitors seem to be able to get things to field a lot quicker than we can,” he continues. “Can we really adapt and transform our acquisition processes so that we can keep up with the way technology is going and maintain [our] lead?”

In addition to speedier development and acquisition of next-generation technologies, the sciences need more students graduating from science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, Col. Luker says. The AFRL has outreach programs to tap elementary, middle and high school students, knowing that waiting until college is too late to lure them to STEM studies. The fields have witnessed gradual drops in student interest, he offers. “Part of it is due to the fact that our economy has shifted away from [manufacturing], and we’re more of a service-based and information-based economy now,” he shares, offering a personal opinion rather than voicing a stance as an Air Force officer. “To get an engineering degree is not an easy path to take. There are more areas in our economy where I can basically make a decent living without having to go through the work that it takes to get a STEM degree.”

Hoping to turn the tide, officials are appealing to students’ desire for innovation. They say a unifying national mission akin to the space race decades ago is needed. “We had this national imperative, and everybody was onboard with this kind of vision, this kind of goal of where we needed to go as a country,” Col. Luker says. “To some extent, right now, we don’t have that same sort of driver. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the United States hasn’t had that strategic near-peer competitor that really gets everyone to rally around the same sort of vision or goal of where we’re going for the country.”

Funding presents itself as another big challenge for the research lab, Col. Luker says. “Budgets are declining, and there’s no indicator they will start to recover anytime soon. At the same time, aerospace system costs have continued to escalate at an exponential rate. A big focus of the LCAAT program … is to break that cost growth curve, taking advantage of both [unmanned aerial vehicle] capabilities and new manufacturing technologies to ... make the systems more affordable.”

Relying on industry alone to foot research and development projects is not the answer. “Industry always funds areas of research that they feel they need to do to maintain a competitive advantage,” Col. Luker says. “I don’t think it’s been a lack of funding by industry [causing the technology gap].” A practice that has given the United States its historical advantage is government-funded research labs and military laboratory systems, he says. “This is one of the areas where I feel that our system that we’ve set up actually is one of the things that keeps us ahead of some of our foreign competitors. We are able to take more risk than I would be able to take if I was just in a company where I’m worried about the bottom line, and I’ve got to produce results in the near term. Our system allows us to take a little more risk and focus more on long-term investments.”

It was government-funded research that introduced the world to the Internet and the Global Positioning System, Col. Luker offers, and federal investment in the B-2 bomber program spawned technology in structural composite that transitioned to products such as golf clubs and other sports gear. “There is a natural transition of technologies that we developed for the [Defense Department] that helps push the U.S. economy,” he says

Throwing more money at research and development is as much of a solution as finding ways to reduce the time to take technology from concept to field. It can take up to 12 years to go from an idea to a fielded system. “The Air Force has been looking at ways to reduce that portion of the acquisition cycle as well,” says Col. Luker, who will remain at the directorate as deputy director until summer 2018. “We also need, within the lab track, to try to develop the technologies quicker.”

Personnel issues weigh as heavily on leaders as technology and financial ones. After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the Defense Department experienced a major drawdown, and for several years the Air Force imposed a civilian hiring freeze. “This created a ‘bathtub’ in our overall civilian demographics,” Col. Luker explains, using a common business term to illustrate an organization that has many seasoned employees and new hires but a dwindling middle management corps. If illustrated, the effect would look like a bathtub. “We’re approaching the leading edge of that bathtub, where we’ve got a large percentage of our population currently eligible for retirement within the next five to 10 years. That’s a lot of experience about to walk out the door, and we need to transfer as much of their knowledge as possible to the rest of our work force before they leave.”

Comment

Air force jobs

good news and it will create thousands jobs in Air force.

Comments