China’s Deep Fake Law Is Fake

In late 2022, the People’s Republic of China issued the world’s first deep fake regulation. The communist country sought to limit artificial intelligence creations, or deep synthesis, that went against government interests.

“No organization or individual may use deep synthesis to engage in activities harming national security, destroying social stability, upsetting social order, violating the lawful rights and interests of others, or other such acts prohibited by laws and regulations,” the law says.

These general principles criminalize actions that are left to wide interpretation.

“[Organizations or individuals] may not produce, reproduce, publish, or disseminate information inciting subversion of state power or harming national security and social stability; obscenity and pornography; false information; information harming other people’s reputation rights, image rights, privacy rights, intellectual property rights and other lawful rights and interests; or other such content prohibited by laws and regulations,” states the regulation.

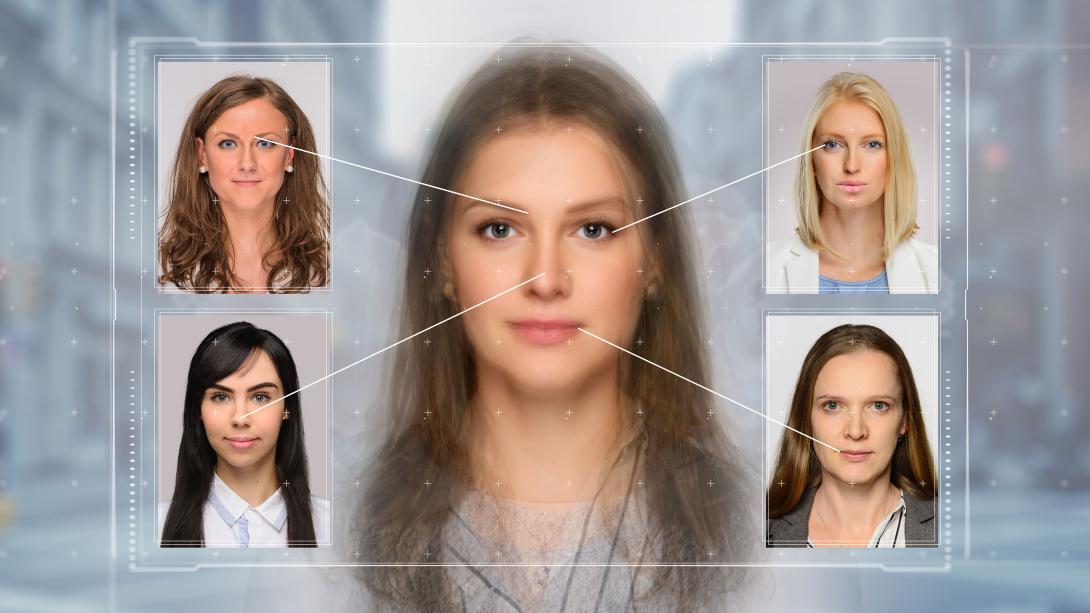

The Cyberspace Administration of China published the novel regulation, aiming to limit the use of algorithms that mimic a person’s voice and appearance and could create content in which a person does or says things they never did.

The term “deep fake” is a combination of “deep learning” and “fake” and refers to realistic-looking video or audio clips created with artificial intelligence. The proliferation of various artificial intelligence tools allows nonexperts to, for instance, use the image and voice of a government leader and program the algorithm to make this realistic avatar say things that could have adverse effects on the individual or the country.

Deep fakes have been used in disinformation campaigns with limited results. The technology is relatively easy to identify, and reputational damage has not been widespread. But at an economic level, even a little damage can be a tempting business opportunity for adversaries.

Jack Cook, an American University graduate student, offered a case where criminals used deep fakes to produce a bounty: “Businessman-turned-celebrity Elon Musk is promoting a new cryptocurrency investment, and all you need to do is transfer funds to a crypto wallet and the returns will be guaranteed; after all, you’ve heard stories from friends who have made money from Musk’s other endorsements.”

After the video circulated for many days on social media, Musk clarified it was fake. By the time he tweeted “Yikes. Def not me,” people had already “invested” in that false business opportunity. According to media reports, scammers made at least $1,700 and probably more before the content was taken down.

Given the variety of tools deep fakes provide to malicious actors, there have been other initiatives to regulate this area where innovation and free speech meet.

The European Union is evaluating possible regulatory alternatives. The first factor considered is that “deep fake technologies can be considered dual-use and should be regulated as such,” stated a policy document. This means that limitations should strike a balance between technological advancement, free speech and law enforcement.

But this same document does not find that regulatory sweet spot and places responsibilities back with the citizen. “The overall conclusion of this research is that the increased likelihood of deep fakes forces society to adopt a higher level of distrust towards all audio-graphic information,” the document says.

While the European Union has left the issue to member states and individuals, the United States has seen only three states limiting the use of these technologies.

Virginia, Texas and California have enacted laws. Virginia’s law is centered on pornographic deep fakes. California and Texas laws cover disinformation intending to influence election results. While there have been several federal initiatives, they have yet to go through Congress.

China’s regulation is the first of its kind, but its application is patchy. The limits the communist country imposed do not seem to apply abroad, and its content creators apparently have been free to attempt disinformation campaigns against the United States.

“We observed a state-aligned operation promoting video footage of [artificial intelligence]-generated fictitious people,” said Graphika, a company that studies online communities and disinformation, in a widely quoted paper.

The company pointed at attempts by Beijing to disseminate disinformation by creating a synthetic avatar posing as a news anchor and reading a story on the divisive issue of gun control in the United States.

“This is the first time we’ve seen this in the wild,” Jack Stubbs, vice president of intelligence at Graphika, was quoted as saying.

The Chinese government has not commented on the company’s accusations.

The company spotted these videos with few online impressions and little virality in late 2022. Since then, other nefarious actors have experimented with these techniques.

“In the weeks since we identified the activity described in this report, we have seen other actors move quickly to adopt the exact same tactics,” the report added.

China’s rule by law seemed far from the rule of law.

Still, the regulation demands that content creators clearly indicate on the material, with a label or watermark, that it is a computer-generated avatar.

Should this regulation be violated, those involved in creation and distribution could face fines of up to $14,500 and other “punishment according to the provisions of laws, administrative regulations, and departmental rules,” including both civil and criminal prosecution.

One anomaly in the Chinese text is absent in other regulations published thus far. The Asian country intends to put limits not only on deep fakes but also on other emerging media technologies.

“The fact that China’s proposed restrictions cover produced text, picture augmentation and virtual sceneries in addition to deep fakes shows that the country is considering the potential effects of developing technologies on the stability of its system more generally,” said Giulia Interesse, editor, China Briefing.

“So far, deep fakes have not been deployed to incite violence or disrupt an election. But the technology needed to do so is available. That means that there is a shrinking window of opportunity for countries to safeguard against the potential threats from deep fakes before they spark a catastrophe,” said Charlotte Stanton, former fellow in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Technology and International Affairs Program.

Deep fakes’ low impact could be attributed to viewers finding avatars odd and not quite credible. Among the easiest signs to spot a fake are the movements of the eyes and face.

“Telltale signs of a deep fake include abnormalities in the subject’s breathing, pulse, or blinking. A normal person, for instance, typically blinks more often when they are talking than when they are not. The subjects in authentic videos follow these patterns, whereas in deep fakes they don’t,” Stanton wrote.

Still, history would have been very different had this technology been refined.

At the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a video showing an avatar posing as Volodymyr Zelenskyy asked people in his country to stand down and not oppose the advance of the aggressors.

Moscow-friendly social media accounts promoted this false statement, and hackers distributed it further by breaking into media outlets’ web pages.

The Ukrainian president responded with another video stating, “If I can offer someone to lay down their arms, it’s the Russian military. Go home. Because we’re home. We are defending our land, our children and our families,” said Zelenskyy in early March of 2022.

At the time, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter said the fake video was removed from their platforms. Meanwhile, on Russian social media, the deceptive material was distributed and boosted, according to media reports.

The Cyberspace Administration of China published that this new regulation was enacted to “promote the core values of socialism,” without delving deeper into the specifics of which content complies with those parameters.

Comments