Defending Industrial Control Systems From Cyber Attacks

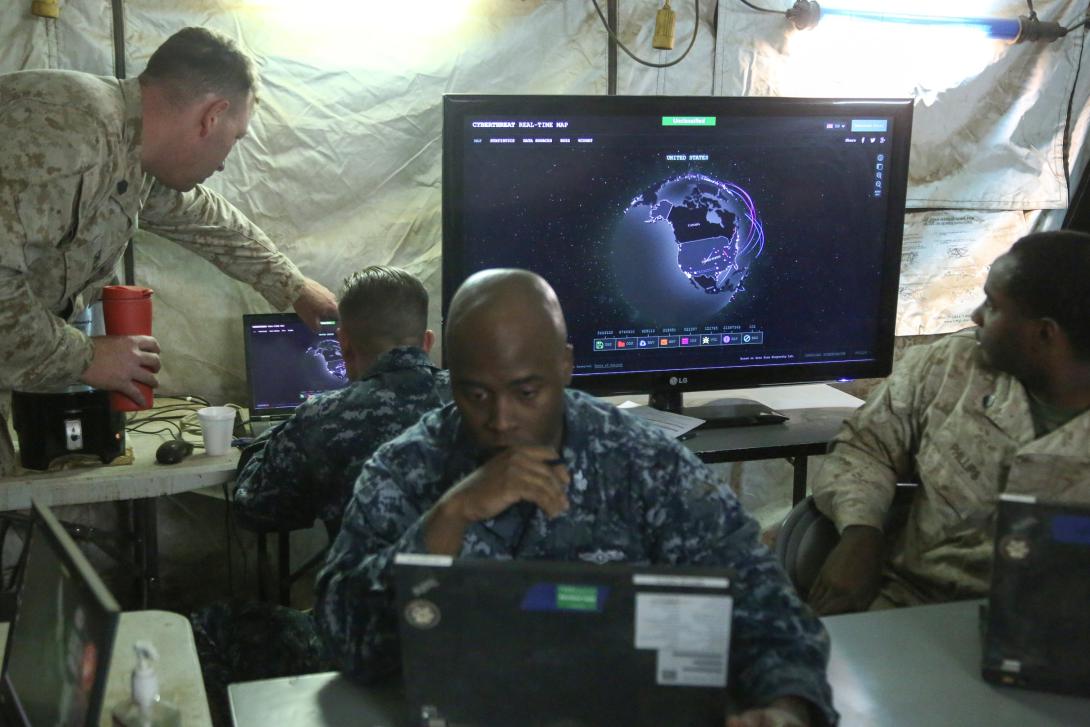

Cyber capabilities have dramatically transformed the battlefield and how conflicts are resolved. Traditionally, battles were fought in conventional domains—land, air, sea, space—using kinetic, psychological and economic means to defeat opponents. In the cyber realm, anything goes. There are no rules. And adversaries are developing advanced cyber capabilities just as quickly as the United States, threatening critical infrastructure and other systems. So-called cyber-to-physical attacks, when hackers target physical buildings, networks and sites, demonstrate the potentially catastrophic results of a successful campaign against power, water and transportation services.

Securing the cyber-to-physical realm is one of the most important issues facing the defense community today. Many of the nation’s critical infrastructure control systems are outdated and go unmonitored for attacks. Gaining better visibility into these systems will be paramount because an attack could cripple the physical world.

How are today’s hackers attacking control systems? How are attacks leveraged on the battlefield, and more importantly, can the U.S. military defend against targeted cyber attacks?

Cyber attacks reach far beyond warriors on a traditional battlefield. They also affect civilians and cause second-, third- and even fourth-order effects—ripple effects that might disable well beyond an attacker’s primary military target.

Targeting control systems via cyber methods makes sense for many reasons, but ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu, in The Art of War, might have said it best: “In the practical art of war, the best thing of all is to take the enemy’s country whole and intact; to shatter and destroy it is not so good.” Why destroy a city with kinetic prowess when a well-targeted cyber attack will do?

The psychological aspects of cyber attacks that criminals can leverage are dramatic. The ability to plunge bustling cities into pitch darkness sends a powerful message that can strike fear into modern civilizations.

Meanwhile, many types of interconnected systems, from fuel to power, water and even air conditioning, have been caught in hackers’ crosshairs and will continue to be targeted. Interconnected control systems let authorities manage and monitor the battlefield and the resources required to operate the infrastructure. These systems contain many components, including servers that run proprietary and often highly vulnerable software, programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and embedded devices and sensors. Each component has its own attack surface, presents its own risks and can be found everywhere from power grids to battleships.

Defending control systems from cyber attacks requires a thorough understanding of all the components adversaries might target. Placing control system components into general categories lets users better understand and appreciate the challenges of securing them. For instance, engineers responsible for operations use many supporting systems to develop, monitor and maintain control-system environments. These include human machine interfaces (HMIs), control servers, data historians and engineering workstations. Most supporting systems run on a server and have proprietary software packages installed. Engineering workstations often are overlooked as part of the control system, but they should be included in security discussions.

Logic controllers also must be secured. Typically, the PLCs or microcontrollers are programmed with the logic to control a process and accept feedback throughout the process to control actions or raise alarms. For example, a PLC would be wired to the pumps and sensors used in a fuel system to read fuel levels and control the movement of fuel. Devices such as pumps and valves change state according to the PLC’s directions. Intelligent electronic devices, on the other hand, can make decisions on their own or raise threat alarms. Sensors, which can be part of many devices or stand alone, allow for monitoring and are part of the feedback loop to the PLC. Sensors measure anything from revolutions per minute to temperature and are critical components of the control system.

Cyber-to-physical attacks leverage an array of vulnerabilities in any component of the control system to achieve their objectives. For example, an attack on the Ukrainian power grid in 2015 targeted embedded devices as well as the operating systems and software used on supporting systems.

HMIs and other control servers let attackers modify settings on downstream components and disguise what operations personnel see. Even small process changes over time can cause damage if they are not identified and fixed.

The HMI is one of many examples where traditional information technology and operation technology converge. Many HMIs run on traditional computing hardware and operating systems but use proprietary software that is often outdated, unpatched and highly vulnerable to attack. Cyber criminals target HMIs because they provide access to a visual representation of the very process they are attacking, making it easier to understand. What was designed as a tool to monitor operations has become a favorite attack starting point.

The vulnerabilities of logic controllers are serious and widely publicized. Because the PLCs and microcontrollers provide the logic and control of the process, if attackers gain access, they can modify the process. PLCs have been around for a long time, including during a period when security was not a major concern. They typically run on an embedded operating system, which means they lack many of the security functions of traditional operating systems. PLCs rarely are patched or upgraded because this requires stopping the process to do so.

Typically, control systems are designed to have 15- to 30-year life spans, a duration that leaves most environments with a mix of old and new technologies. Unfortunately, there are no foolproof ways to patch system vulnerabilities. The answer once was to create “secure enclaves” where these systems lived and avoided exposure to less secure networks.

In most cases, these enclaves cause additional security risks by making it harder to update systems and devices. Often, managers end up with an environment far less secure and riddled with hidden routes added by engineers and operators to facilitate their jobs. Skilled attackers readily identify how personnel access these enclaves and can piggyback onto workarounds to access networks via other trusted systems or by leveraging media such as USB flash drives.

As the surface of attack continues to grow, it is critical to look at cyber as its own battle landscape and put the necessary resources behind it. Today, the cyber battle extends beyond computers into the physical realm and can have devastating effects if officials fail to prepare.

Kevin Davis joined Splunk in October 2014 and is now vice president of the company’s public sector business. The views expressed here are his alone.

Comments