Mind the Cyber Gap

As China continues to threaten U.S. national security through a whole-of-society warfare strategy, a government-private sector partnership must be a fundamental component of the U.S. government’s approach to information advantage and countering China’s attacks.

Societies enjoy new prosperity but also suffer new vulnerability in an increasingly networked world. The 2020 Cyberspace Solarium Commission describes the cyber landscape’s strategic dilemma as one that “requires a level of data security, resilience and trustworthiness that neither the U.S. government nor the private sector alone is currently equipped to provide.” What has been largely missing from the public discussion, however, is how to address growing shortfalls in agility, technical expertise, and unity of effort within the U.S. government and between the public and private sectors in informational power, where no one agency or individual has primacy within the diplomatic, informational, military and economic (DIME) framework. This is a gap that adversaries—both state actors, such as China and Russia, and nonstate actors, such as the Islamic State—have exploited.

China threatens U.S. national security through coercive cyber-enabled operations in the information environment. According to the U.S. Defense Department’s 2020 report on military and security developments involving China, these operations further China’s strategic objectives by targeting cultural institutions, media organizations, business, academic and policy communities in the United States, other countries and international institutions. China’s military has stressed implementation of the “Three Warfares” concept—composed of psychological warfare, public opinion warfare and legal warfare—in its operational planning. Chinese information warfare (IW) is coordinated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) but is executed by a wide range of actors. One strength of global information networks is their openness, but this openness also makes networks vulnerable to the CCP’s IW, which targets human cognition and decision making to weaken adversaries’ resolve.

America’s top intelligence officials believe China is the nation’s number one national security threat, and John Ratcliffe, the former director of national intelligence, highlighted the need to give U.S. policymakers unvarnished insights about China’s intentions and activities, such as China’s massive influence campaign against the United States. Avril Haines, the new director, also agrees that “our approach to China has to evolve and essentially meet the reality of the particularly assertive and aggressive China that we see today.” As resourcing shifts to assess China’s threat writ large, ambiguity about who in the U.S. government leads detecting and countering Chinese cyber-enabled IW remains a challenge to winning the information battle.

The Internet’s very nature makes responding to China’s IW campaigns difficult. Renee DiResta’s “Social Network Analysis and the Disinformation Kill Chain” presentation during the 11th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (11th CyCon) explains why fighting online influence operations is complex. The Internet’s anonymity obscures threat recognition, and its multistakeholder governance model makes defending against IW challenging. The profit model for most social media incentivizes user time-on platform and disincentivizes potentially controversial content regulation. The speed at which information can be transmitted, or its potential “virality,” makes recognizing and responding to online influence operations even harder. Borders are largely ineffective in defending against cyber-enabled influence efforts, and the low cost of entry and the proliferation of cyberspace touchpoints in most people’s daily lives make countering IW at the speed of relevance daunting.

That said, emerging of methods for identifying and analyzing digital IW can improve detecting and countering China’s IW. DiResta’s methodologies include analyzing how people receive info, who people decide to follow and trust, and how and why people congregate. Shifting intelligence resources to assess the Chinese threat overall is unlikely to adequately fuel cyber-influence analysis. Thorny content-related policy challenges, such as freedom of speech considerations, can be contentious. Uncertainty about which U.S. informational power stakeholders should triage/assess, prioritize and operationalize potential responses to these threats does not help.

Cyber-enabled influence operations involve gaining access to online users and exploiting their cognitive vulnerabilities with tailored content to produce particular human behavior. Cyber-enabled influence can be supported by noncyber elements or can be conducted completely online. Herb Lin’s “Cyber Operations v. Information Operations” discussion, also during the 11th CyCon, describes how the impacts can include informing, distracting, obscuring, confusing, misleading and provoking. “Cyber influence has potential pre-conflict operations applications, such as establishing accounts for influence during conflict, ongoing participation and engagement to establish credibility as a source or party and laying the groundwork for others to do work as “influence force multipliers.” Influence operations can support deterrence efforts, complement kinetic activity and even precipitate cessation of conflict.

Lin characterizes influence operations as propaganda, chaos-production and leaks and suggests four approaches to protect against them. This is especially helpful, as the U.S. government’s nomenclature is murky and stakeholder roles and responsibilities are even murkier. Lin’s approaches include avoidance, detection through the identification of the ongoing information campaign, defense (media literacy, fact-checking or limiting disinformation) and recovery (issuing corrections or retrospective attribution). Yet, not all target audiences will want to be protected, further complicating U.S. government alignment of the “I.”

The Internet and information are also a double-edged sword for China. On the one hand, China’s booming economy and Chinese “netizens” have wielded incredible power, shaping international discourse.

According to Gabriel Fung’s article in The Diplomat, “Parsing China’s Cancel Culture,” instances of international brands accused of offending China indicates 120 such incidents since 2009, with as many as 40 in 2019 alone. China’s global market share and its online influence have enabled robust implementation of its whole-of-society “Three Warfares” concept.

On the other hand, worried the Internet presents what the 2019 Asia Pacific Regional Security Assessment by the International Institute for Strategic Studies described as “a nearly existential threat” to the CCP, China’s “comprehensive framework of laws, policies and institutions … exercise tight control over online discourse and behavior.” According to this assessment, China views itself as engaged in “an ideological confrontation in cyberspace, seeking to counter foreign ‘hostile forces’… which [contribute] … to protests that have overthrown authoritarian governments elsewhere.” It also describes the CCP’s view of state control over cyberspace as “integral to China’s national security.”

China’s IW in the ideological battlespace is, for example, operationalized by China’s 50-cent-army, Internet trolls hired by the CCP, described in the Epoch Times article, “China’s 50-cent Army Fabricates 450 Million Fake Posts a Year to Spread Lies and Hatred.” It generates an estimated 448 million messages a year. Some messages criticize the United States or play down the existence of Taiwan, while others attack social media posts critical of China on topics ranging from Hong Kong’s extradition law to the pandemic. Some believe China, despite its efforts, may not actually be winning the battle of the narrative, giving the United States a chance to improve its approach to information.

U.S. Great Power Competition, as described in the 2018 National Defense Strategy, highlights both competing with China and preparing for conflict. Optimizing informational power is a key element of both, and America must reform its informational framework now. Donald M. Bishop’s article, “DIME, not DiME: Time to Align the Instruments of U.S. Information Power,” states the U.S. government’s four instruments of information power include the White House’s and executive department’s public affairs, the State Department’s overseas public diplomacy program, the military’s information operations and the five international broadcasting networks under the U.S. Agency for Global Media. Countering China’s IW with “no one button to push” within the U.S. government is tricky when the various instruments, according to Bishop, have “different authorities, appropriation streams, boundaries, lanes, rules and doctrines.” Informational power stakeholders must refine understanding of IW threats, align and support each other’s efforts and work toward common informational objectives. Only then will the United States be able to more effectively leverage nongovernmental U.S. informational power within academia, nongovernmental organizations, the media, entertainment, advertising and other U.S. Internet content, evolving its approach in the dynamic information landscape.

Some advocates even go so far as to call for bringing back the U.S. Information Agency. Others argue synchronization of the “I” cannot be achieved by merely growing the government’s bureaucracy. There is no single path to achieving U.S. information competitiveness, but designating a position or agency with primacy over government’s “I,” if appropriately empowered with resources, authority and a respected “seat at the table” of national security decision making, is a good start. The designated information czar could appoint responsibility for particular objectives, such as funding and authorities’ advocacy within the government and seeking partnerships and collaboration with nongovernmental American and international informational stakeholders.

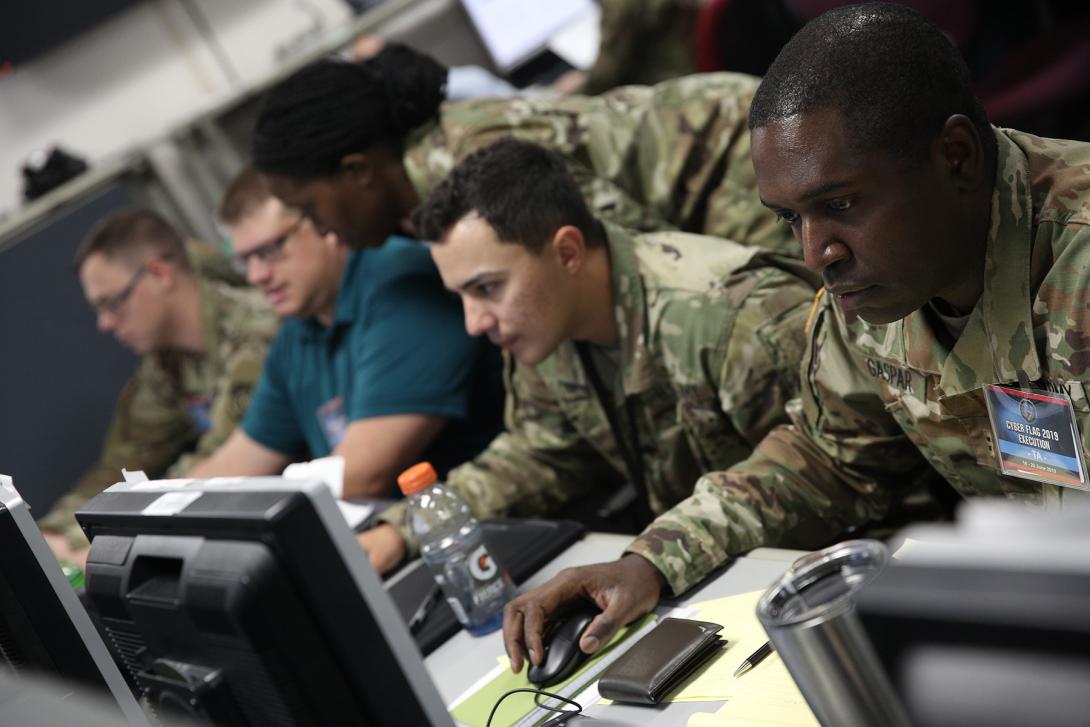

The National Defense Authorization Act (FY20 NDAA) section 1631 attempts to streamline the Defense Department influence operations by clearly articulating the role of the Defense Department in countering precisely this type of threat, authorizing operations “in response to malicious influence activities.” Authorities and resourcing are not optimized for these operations, however, and the NDAA additionally mandated designation of a principal information operations advisor (PIOA) responsible for oversight of policy, strategy, planning, resource management, operational considerations, personnel and technology development across all the elements of information operations of the department.

A report by the Government Accountability Office titled, “Information Operations: DoD Should Improve Leadership and Integration Efforts,” was published in October 2019. Last October, the Defense Department named the undersecretary of defense for policy as the PIOA to help improve its ability to integrate and supervise operations in the information environment. This is a step in the right direction, because they can guide the reform efforts of other U.S. government informational power stakeholders and enable a better transition to a unified government information strategy. But efforts to streamline the Defense Department’s “I” remain insufficient to effectively compete. Ultimately, a government-private sector partnership must be an integral part of the government’s approach to information superiority to effectively counter China’s whole-of-society “Three Warfares” strategy.

Cmdr. Erika De La Parra Gehlen, USN, J.D., is a student in the Cyber & Innovation Policy Institute Gravely program at the U.S. Naval War College. She is an active-duty judge advocate in the U.S. Navy and, most recently, the legal advisor to Special Operations Command, Pacific. Contact her on Twitter at: @erikagehlen or on LinkedIn at: linkedin.com/in/erika-gehlen-7797b61.

The views expressed in this essay do not represent the official position(s) of the Naval War College, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Comments