Reworking the Working Capital Fund Can Save Cyber

The Defense Department must break from the Working Capital Fund model and make a strategic investment to build up new capabilities at cyber research and development commands. Failure to overcome the barriers generated by that model to improve the efficiency of these organizations would surely hand the technical advantage to adversaries who can innovate faster.

The United States’ prosperity and security is currently being challenged in the cyber domain. The Defense Department relies heavily on U.S. Cyber Command to conduct operations yet lags in developing a capability development workforce. Traditionally, research and development commands would be responsible for capability development. However, these commands use the Defense Working Capital Fund model to improve efficiency. While efficient, the Working Capital Fund (WCF) model creates barriers to rapid growth in new areas like cyberspace.

Some organizations within the U.S. Defense Department have a large cyber development capability, but the department as a whole has not built up the workforce and infrastructure necessary for persistent cyber operations. Currently, the majority of cyberspace capability development is contracted out to private companies at great expense to the department. To tackle previous research and engineering challenges, research and development (R&D) commands, such as the Naval Information Warfare Centers and Air Force Research Lab, were created. Prior to the 2000s, these commands were responsible for great engineering successes, including submarine launched ballistic missiles, stealth aircraft and even the Internet.

These commands are places that logically and positionally should be leading research and development of cutting-edge cyberspace operations capabilities. They have large staffs of highly educated civilians who are not required to rotate jobs every few years like uniformed personnel. Their mission is largely to conduct research and develop new capabilities for the operational warfighter. However, over time, scientists within the research and development commands often begin to prioritize academic work over projects that directly benefit the warfighter. This evolved into one of the driving issues behind creating the WCF—allowing operational customers to fund development centers that directly benefited them. In 1992, the Defense Working Capital Fund was established as a way to make research and development organizations operate more like a business.

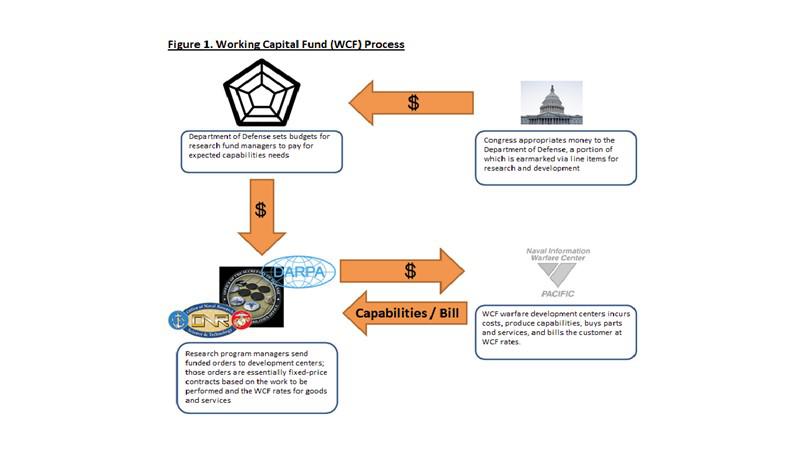

In a nutshell, Congress provides a direct appropriation to an R&D fund. This fund is then dispersed to the armed services by the Defense Department. The services then appropriate portions of the budget to the relevant arms. Organizations throughout the chain of command that retain R&D budget then determine their requirements and contract these requirements to WCF organizations, which then execute the project. These projects may entail research or capabilities development from warfare development centers or other forms of acquisition. In this way, the WCF commands act similarly to a contractor with other Defense Department organizations as their customer. They are reliant on project funds coming in to pay for their work, as the funds are not directly appropriated.

Each service has its own WCF with slight variations on the policies governing its use. This forces it to operate more efficiently and focus on what the warfighter needs versus conducting research for research’s sake. Working capital creates an environment of competition as WCF organizations must now compete with defense contractors.

However, WCF organizations increasingly cannot adapt to the changing global environment to meet warfighter needs. This is particularly true for cyberspace operations where the domain evolves rapidly.

Cyber is unlike anything many of these organizations have worked with before, and their workforces lack the skills and experience to conduct the cutting-edge work that is the mission of such research and capability development centers.

One key point is that the Defense Working Capital Fund requires research and development organizations to maintain a zero-sum budget and spend every dollar of the budget on line items directly related to the assigned contract. Therefore, no research and development command can save or reallocate money toward training individuals or researching other topics of interest on the horizon. In the case of cyber development, this leaves working capital funds in a chicken-and-egg scenario, especially for those without existing cyber contracts. They cannot get funding to train individuals for cyber projects without customers that already pay for cyber projects, yet they cannot bring in projects in new areas without the expertise training affords.

In addition to the WCF’s contract limitations, it is not a project sponsor’s responsibility to fund workforce training in lieu of developing capabilities that meet their requirements. The sponsor has many other options to choose from within the WCF process; therefore, there is no reason to fund development center training. Further, reaching out to sponsors requesting funding—either specifically or out of other, existing project funds—to establish a cyber training pipeline would counter any motive for the sponsor to provide funding on future cyber capabilities projects due to lack of confidence in the organization’s workforce. They would simply seek services from other more capable development organizations because it saves money. This is one of the reasons the U.S. Cyber Command maintains its development capabilities rather than handing that responsibility over to the system commands and warfare centers that traditionally would lead those efforts.

While hiring talent would normally be an option, top talent is dissatisfied with the incredibly slow growth and the lack of projects that utilize their expertise. This forces top talent to be underemployed for long periods of time while waiting or compels their departure from the organization. In this way, working capital funds hinder rapid growth, and these organizations now require a strategic level investment to overcome obstacles and meet the challenges of cyber capability research and development.

Additionally, the WCF creates significant inflexibility problems for the rapidly changing cyberspace domain. Cyber operations forces cannot withstand the normal Defense Department acquisition cycle with which the WCF has grown. Projects spanning years and utilizing waterfall development methodologies will be obsolete before they’re ever deployed. With the WCF closely tied to fiscal year spending requirements that are sometimes planned for years in advance, it is an unacceptably slow and rigid funding process. And, it often results in projects that continue to be worked on for years after they have been determined obsolete.

As a case study for the glacial pace at which the WCF moves, some WCF-funded organizations announced in 2013 that they had set a goal of developing cyber capabilities. Yet, as of this writing, they have not developed a workforce capable of producing cyberspace operations capabilities, and they struggle to retain personnel qualified for even basic exploitation development. In the years since the initiation of this goal, the private sector has introduced many sophisticated defensive measures, such as Microsoft’s Control Flow Guard. If these organizations are to catch up to their private-sector counterparts and reclaim their place in the Defense Department as centers for cutting-edge research and capability development, they cannot continue the slow growth that the WCF forces.

For these reasons, many of the commands and entire services that used to rely on a WCF have largely abandoned use of the construct. Even the Navy, the most ardent supporter of the WCF, in its own report found the construct incredibly wasteful. And the one thing a WCF is supposed to provide is financial efficiency, even at the cost of mission impact and effectiveness.

To overcome these challenges, strategic-level investments must be made in the WCF commands expected to develop cyberspace capabilities. Project funds cannot and should not be used to develop the workforce required. Their cost-savings goals and inflexible schedules cannot support cyberspace capabilities development, except where a highly talented workforce is already established and has consistent project flow. In addition, these strategic investments in the WCF must encompass enough funds in a short amount of time to properly equip and train their employees. While alternate funding mechanisms exist for WCF commands—such as the Naval Innovative Science and Engineering (NISE) fund—these organizations have strict guidelines that prevent investments large enough for such an effort. The overwhelming amount of training and equipment required to build a workforce in a totally new domain cannot be done piecemeal and spread out over the years.

Once training and equipment have been purchased, WCF organizations that handle cyber projects should move away from the WCF-style contracts with billable hours only to a specific project to a mission-funded model. Because no hours are charged to specific projects, employees can shift their efforts to whatever tasks must be accomplished to push the mission forward. This is especially critical within the cyber domain, where the rapidly changing environment can render certain projects useless in a matter of months. Under the mission-funding process, direct appropriations authorize the Defense Department to incur obligations for such designated purposes as proper training or modifications. This added flexibility will greatly benefit WCF organizations striving to be on the cutting edge of cyber projects.

Empowering the workforce to contract additional training or equipment and to modify development project requirements as needed will, in the long run, be more effective and more efficient than working capital funds. This separation from established WCF processes also facilitates experimentation from the new workforce. Freedom from tight project funding allows them to form and reform teams and try different industry methodologies and best practices. This experimentation is best served in a safe environment without worrying about running out of project funds.

The Defense Department needs all of its components operating at maximum effectiveness to succeed in the cyber domain. With strategic investment, WCF organizations can overcome their glacial pace and create an environment for exponential growth. Without it, the organizations cannot hope to develop new expertise in a timely manner to assist in this mission without severe effects on other projects.

Breaking into a completely new field is difficult enough. Reworking WCF processes is the only clear way for the Defense Department to develop an expert R&D workforce capable of tackling rapidly changing environments such as the cyberspace domain.

Lt. Cmdr. Derek S. Bernsen, USNR, is a cyber warfare engineer officer who recently transferred to the U.S. Navy Reserve. He has a master’s degree in computer science from Georgia Tech and is a graduate of The Citadel. The views expressed are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Defense Department or the U.S. government. Contact him on Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/zibzntyd/

Comments