Destructive Cyber Attacks Increase in Frequency, Sophistication

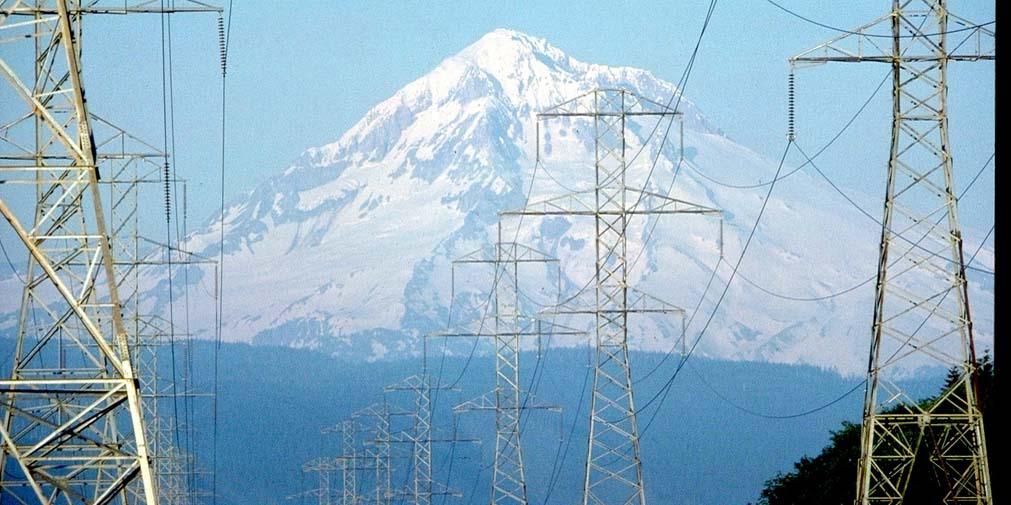

A more diverse group of players is generating a growing threat toward all elements of the critical infrastructure through cyberspace. New capabilities have stocked the arsenals of cybermarauders, who now are displaying a greater variety of motives and desired effects as they target governments, power plants, financial services and other vulnerable sites.

But concerns come from not just evolving and future threats. Malware already in place throughout critical infrastructure elements around the world might be the vanguard of massive and physically destructive cyber attacks launched on the say-so of a single leader of a nation-state. Physical damage already has been wrought upon advanced Western industrial targets.

Adversaries are changing their tactics and techniques on a daily basis, says Shawn Henry, president of CrowdStrike Services, and their sophistication level has risen substantially. They also are aiming at a much broader target set.

The biggest concern is the critical infrastructure, particularly supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, he offers. Experts have found remote access tools, or RATs, in SCADA systems over the years. These RATs would provide outsiders with the ability to control the infrastructure devices. “There are back doors that people don’t know about in many, many systems all the time,” Henry states. “Hundreds or thousands of industrial control systems have been infiltrated by malicious code.”

While most awareness of cyberthreats focuses on data theft, data destruction is a major menace. Adversaries who can steal data can destroy data as well, Henry points out. They also can damage the computers on which the data reside. These destructive attacks have increased in number over the past few years, he says. “Computers themselves—whole parts of networks—have been destroyed,” he declares. “[This is] physical destruction—malicious code actually is used to physically damage hardware, and that is of grave concern.”

Several examples exist in which industrial systems have been damaged physically by malicious code, Henry continues. Late last year, a steel company in Germany suffered severe damage to its blast furnace when SCADA-embedded malware prevented the furnace from being shut down properly. And the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT) warns that a variant of the BlackEnergy malware has compromised many industrial control systems through their human-machine interfaces since 2011. Experts have traced this malware back to the Russian government, Henry reports.

Henry is a former executive assistant director of the FBI who started working in cybersecurity at the bureau in 1999. He offers that the cyberthreat has been growing steadily over the past 15 years, but only over the past two years has the general public started to learn more about it. The U.S. government now is talking about the threat from specific nation-states—China, Russia and Iran, for example—in ways it never did previously, when that type of information always was classified.

The recent U.S. government announcement of Chinese hacking into the personnel records of 4 million current and former federal workers, according to the Office of Personnel Management, does not surprise Henry. “It’s not a new revelation—it has been going on a long time,” he says. “It’s not indicative of something new—it’s business as usual. It’s what I see every single day across companies and government institutions.”

Henry describes this penetration of federal employee records as an espionage collection program: “It’s about gathering dossiers on those who have access to sensitive information [and] are employed in certain locations. It’s a way to target people when they travel to China.

“For a thousand years, espionage has worked by targeting human beings who have access to information and then approaching them to gain their cooperation,” he continues. China’s espionage efforts in the United States have been ongoing for some time, he adds, and they range from Chinese students working on behalf of the government to cyber hackers who collect government, commercial and intellectual property information. These efforts are part of a 20-year plan to supplant the United States on the world stage.

Henry points out that China once declared to the U.S. government that it does not hack, and it demanded proof of what it described as spurious allegations. In turn, the U.S. government indicted five Chinese nationals for specific illegal acts of cyber hacking, and it provided strong conviction-level evidence backing those indictments. When this was presented to Chinese officials discussing cyber issues at a negotiating table, the Chinese officials walked away. “A government that repeatedly says, ‘We don’t do this,’ is full of nonsense,” Henry says. He adds that his company has direct attribution back to the Chinese government. “Time and time again, every single day, U.S. companies are being breached and losing intellectual property.

“People need to know that just because they haven’t seen it doesn’t mean it’s not there,” Henry contends. “It’s almost like a germ—you still have to wash your hands before you eat.”

For the near future, the critical infrastructure offers the greatest potential for a devastating attack, Henry suggests. But another likely target is the financial services sector. He relates that two years ago, Iran targeted financial services for denial-of-service attacks for several months. “One of the United States’ most critical infrastructures was targeted successfully by a rogue nation-state that caused impact,” Henry describes. It was not a devastating attack because the financial services sector is, relatively speaking, “up to speed” in cybersecurity and was better prepared for this type of incident.

Energy is another part of the critical infrastructure that is a tempting target to rogue states and terrorists. These groups specifically have taken aim at the energy sector along with financial services, Henry relates.

Early cybercriminals tended to consist of nation-states and young hackers. The young criminals targeted retailers, while nation-states focused on the defense industrial base. However, over the past few years, every single element of the infrastructure has become a target, Henry says. “There is not a company connected to the Internet that somebody isn’t interested in because everybody has some information of value,” he states. “It’s not just personally identifiable information such as credit card and Social Security numbers, … it really is much deeper and broader than that. It’s about intellectual property, research and development, corporate strategies and information related to mergers and acquisitions.

“The very DNA of every company is exposed, and it’s being exploited,” he emphasizes.

Traditionally, nation-states and loosely knit groups of organized criminals have been the majority of players targeting networks, Henry says. But looking ahead, the threat is likely to evolve into a more asymmetric form comprising rogue nation-states and individuals. This includes multinational terrorist groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Five years ago, the fear among security experts was these groups obtaining weapons of mass destruction such as nuclear, radiological, chemical and biological weapons. Now, these groups are striving for malicious code they could use to disrupt the critical infrastructure, Henry warns.

A large nation-state that has seeded widespread SCADA systems with RATs might have a lot to lose if it were to launch an attack on a country’s critical infrastructure, Henry points out. However, he notes, “during certain types of negotiations,” the nation-state may benefit by having the capability to take action if necessary. Rogue nations and terrorist groups have less to lose and would be more likely to launch an asymmetric cyber attack. And they have an interest in affecting society in a devastating way.

These rogue states and terrorists have changed the cyber landscape. Traditionally, adversaries tended to be a clearly defined set of foes. Now the threat is increasing exponentially, Henry says, and other parts of the world are beginning to connect with the Internet. Some of those newly networked individuals will join the adversarial ranks for profit or power. “As more people get connected, the pool of bad guys increases,” he points out.

Cyber intrusions for profit tend to aim for data that would have broad applications in the online criminal market. On the other hand, industrial espionage tends to be targeted. Information related to how a product, or even a substance such as an alloy, is manufactured would have a narrow market in the cyberthreat community. Stealing this type of secret likely would involve a targeted approach on behalf of a specific client or organization, Henry offers, as is done with fine art thefts. “You wouldn’t steal a Picasso and just put it on the open market,” he analogizes. However, other types of broadly used information are bought and sold in cyber markets.

The Internet of Things (IoT) offers a new set of challenges. Henry believes those working to develop the IoT probably are not paying enough attention to cybersecurity. Instead, they are focusing on increased connectivity, which augments vulnerabilities. However, the IoT poses a threat to individual targets, such as homes, rather than the broad infrastructure as a whole. “The Internet of Things is important. Companies are rushing to market. It’s a hot new area—there is a lot of money to be made. Security is, in my experience, rarely a primary focus in a product [such as this],” he says.

With the broad nature of these threats, responsibility for cybersecurity must be shared between government and the private sector, Henry says. Any government’s fundamental responsibility is to protect its citizens, he warrants, but today’s policies and authorities do not enable government to protect the people from malicious code. Companies must take responsibility to fill that capability gap and protect themselves—not because it is the way it should be, but because it is the reality facing everyone in today’s framework.

While the term information sharing has been “bandied about frequently without a lot of context,” Henry believes that sharing tactical intelligence is more appropriate. Issues to be determined include who is going to use this intelligence, how they are going to use it and what it will be used for. “If the private sector is sharing intelligence, then what kind of intelligence does the government want? What type does it need? What will the government do with it when it gets it, and what can the private sector expect back?” he queries. That framework has not been defined clearly, nor has its infrastructure been developed effectively, he adds.

Companies need not share proprietary information, Henry continues. All the government needs is threat information—the type of malicious code observed and the types of vulnerabilities that were exploited, for example. This can be done anonymously, with companies sharing that information in a way that is of high value to the government without threatening any individual company, he states.

This sharing must be narrowly focused, Henry adds. “If everyone shared what they had, the government doesn’t even have the capacity to take in all of it—it’s just too much,” he warns. “It must be done in a way that enables the government to take mitigating action against specific adversaries.”

No measure, not even defense in depth, will prevent adversaries from getting on the network, Henry continues. “You need to work on detecting the attack so that you’ll be in a much stronger position, once you detect it, to mitigate it,” he says. “If you detect threats early enough, you will have a much better opportunity to ensure that you won’t have substantial damage in your environment.”

For nation-states, the U.S. government must take additional steps. Citing China’s hack of U.S. federal employee records, Henry states that the United States must offer a new type of response. “The change in [hacker] activity is not really new; but the change in the U.S. response has to be new. This has been going on for 15 years, and we cannot just allow it to happen.

“This is a breach of not just information, it is a breach of also our privacy and our network integrity,” Henry declares. “It’s an affront not only to U.S. government employees, but also to the entire citizenry of the United States.” Henry adds that as a former executive assistant director of the FBI, he is someone whose personal data probably is now in the hands of the Chinese espionage officials.

Henry calls for the U.S. government to draw definitive lines with a clear demarcation of what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior, along with consequences. Then, when a nation-state crosses the unacceptable line, it would do so understanding what will happen to it. The response could take place at the diplomatic level or in the economic realm.

“Actions should be taken that have an impact—we need to show them there is a cost for their hacking actions,” he says.

Comments