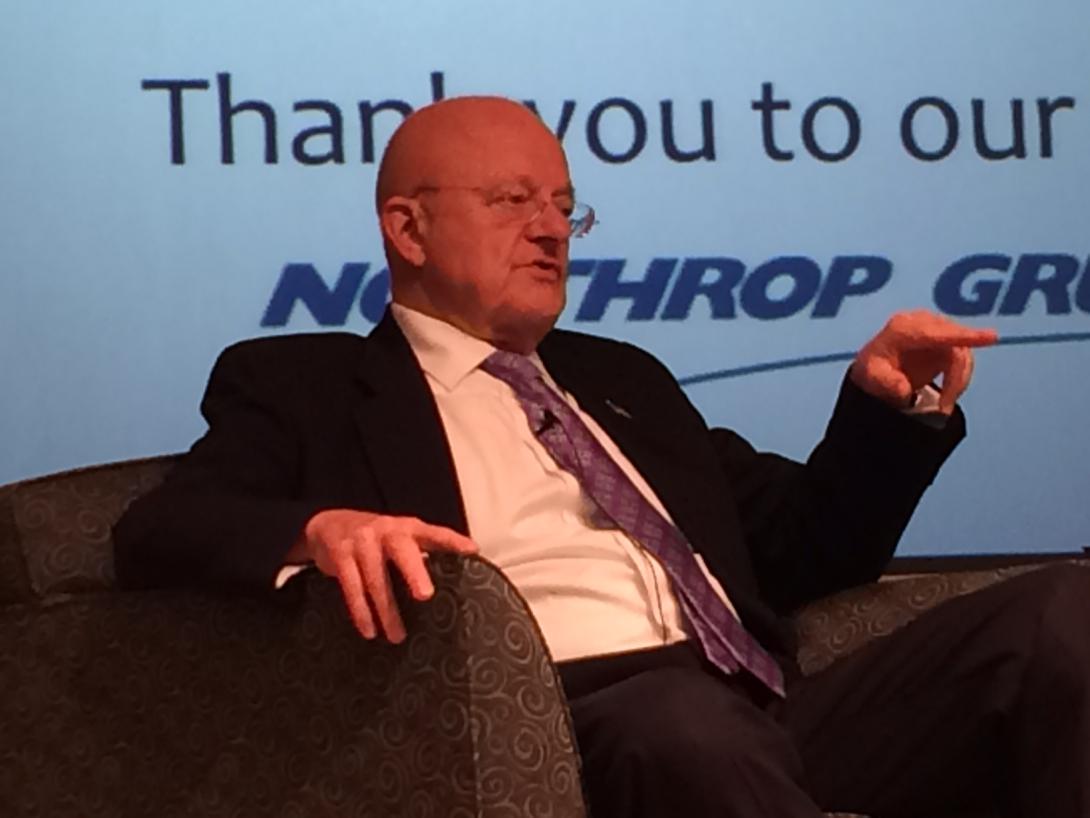

DNI James Clapper Talks Pre-election Uncertainty and Global Instability at EPIC Event

The next 17 days leading up to the presidential election pose a rather vulnerable time for the United States—more so than usual during a transition of power, says Director of National Intelligence James Clapper. “This year, for lots of reasons, people are nervous, particularly for an election cycle that has been sportier than normal,” Clapper shared during at presentation Thursday at AFCEA’s Emerging Professionals in Intelligence Committee (EPIC) speaker series.

The next 17 days leading up to the presidential election pose a rather vulnerable time for the United States—more so than usual during a transition of power, says Director of National Intelligence James Clapper.

“This year, for lots of reasons, people are nervous, particularly for an election cycle that has been sportier than normal,” Clapper shared during at presentation Thursday at AFCEA’s Emerging Professionals in Intelligence Committee (EPIC) speaker series.

Despite the worry, Clapper said, everything will be OK. “We do have a legacy of transition of power going back to George Washington, when he retired in 1797 and turned the presidency over to John Adams. I remember it well,” Clapper quipped during his presentation.

The biting partisan campaigns aside, this election is marked by threats of reported foreign nation-state cyber attacks aimed at influencing the U.S. politics. In a joint statement released this month from Clapper and Department of Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, the U.S. formally accused the Russian government of hacking the Democratic National Committee and other institutions and stealing and emails. “We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities,” the statement said.

The Russian hack is not unlike the North Korean cyber attack on Sony Pictures in 2014, Clapper pointed out. And while the instinct might be to launch a similar retaliatory counterattack, “Well, it’s complicated.” Clapper said Thursday. “In the case of the North Korea attack, when we considered a cyber response or cyber reaction, well then you have the complication that the infrastructure that was used by the North Koreans is in China. That poses legal restrictions about attacking through another country.

“We ended up … sanctioning a bunch of North Korean generals. So they can’t use their credit cards.”

A retaliatory cyber attack on Russia jeopardizes the "perishable and fragile" access to those networks that could help let "us know what they’re doing against us,” he added. “That’s the trade-off. Without divulging what the final decision will be, probably the best options for us are economic sanctions against Russia.”

Beyond the election woes, global instability has strained the intelligence community and has been a major concern for the current administration—and will continue to be so for the next one no matter who becomes president, Clapper said. Two-thirds of the word’s nations face some risk of instability in the next few years. In addition to the current concerns that continue to center on traditional adversaries of the United States, such as Russia, China, Iran and North Korea, the country’s leaders will be in a “perpetual state of suppression” against militant groups beyond the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, or ISIL, he said.

“After ISIL is gone, we can expect some other terrorist entity to arise and be spawned. We’ll have a cycle of extremism which will continue to confront us for quite a while.”

Adding to the list of worries for the coming decades, an underlying catalyst of unpredictable instability will be climate change. “Major population centers will compete for ever-diminishing food and water resources. We’re already seeing evidence of that in several places around the world. This has big-time national security implications,” said Clapper, who might have started his intelligence career at age 12. That summer, he discovered he could tap into radio traffic by the Philadelphia emergency dispatch center by positioning his grandparents’ television knob between channel four and five—perhaps a first “hacking” case, he joked. He spent the summer plotting on a map locations where police responded and created a card file of police code, radio chatter and investigator call signs—or what today’s digital natives might refer to as metadata.

But that passion illustrates what it takes to do intelligence work, Clapper said to the room full of young professionals. It takes research, persistence, continuity and the ability to draw inferences from incomplete data.

The intelligence profession over the past several years has had an extraordinarily public conversation about how it conducts its work, particularly in the aftermath of the Snowden revelations, he said, referring to former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden, who leaked information on the government’s surveillance efforts to news media.

But the talk has not centered on the why, Clapper said. “At the basic level, we conduct intelligence to reduce uncertainties for decision makers. It would be great if we could eliminate them … but that rarely happens.”

Comments