DHS Testing Shows Masks Complicate Racial Picture on Facial Recognition

The best facial recognition systems work very well but showed increased racial disparities in performance when the volunteer subjects wore face masks.

The best facial recognition systems work very well matching people of all races to their file photographs when tested in a real-world scenario, but when the volunteer subjects were wearing face masks, even the better performing systems showed increased racial disparities in performance, Department of Homeland Security officials told AFCEA’s 2021 Federal Identity Forum and Expo Tuesday.

Of the 60 systems tested at last year’s third annual DHS Science and Technology Directorate biometric technology rally, 22, more than a third, met the minimum performance standard—a success rate in acquiring and matching facial images of 95 percent—for maskless volunteer subjects who self-identified as Black or African American. Thirty-two, more than a half, met that standard for self-identified white volunteers without masks, according to Yevgeniy Sirotin, the technical director of the SAIC-managed Maryland Test Facility where the DHS biometric technology rallies have been staged since 2018.

DHS officials say the biometric rallies provide them with comprehensive performance metrics for the tested technologies—including things like transaction times, image acquisition and matching success rates and user satisfaction.

The test facility, which is in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, typically engages a very racially diverse set of volunteers and 2020 was no different, Sirotin said, “Overall, you could see that there are many systems that worked well for volunteers independent of their race.” The test systems were set up to duplicate self-service kiosks used at an airport by departing passengers—they have to both acquire an image of the volunteer and match it to one already on file. The best performers had a 100 percent success rate across all self-identified racial groups.

But when volunteers tried to use the systems wearing face masks, even the top-performing systems failed to reach a 95 percent success rate for those identifying as Black or African American—although they managed to for whites and other racial groups.

The results matter, because, owing to the inequitable global distribution of vaccines and the emergence of new COVID-19 variants, “One year later, we’re all still wearing masks,” said Sirotin, and they’re likely to be a feature of the international travel scene for a while.

“With masks … errors did not increase equally,” he noted, “When people wore their personal face masks, performance declined for some (racial) groups more than for others.”

Importantly, the increased error rate didn’t just result from poorer facial image matching. There was also an increase in failures that resulted from no picture being acquired—and again that disproportionately impacted volunteers who self-identified as Black or African American.

To take the picture, the software controlling the camera has to recognize that the image it is looking at is a face.

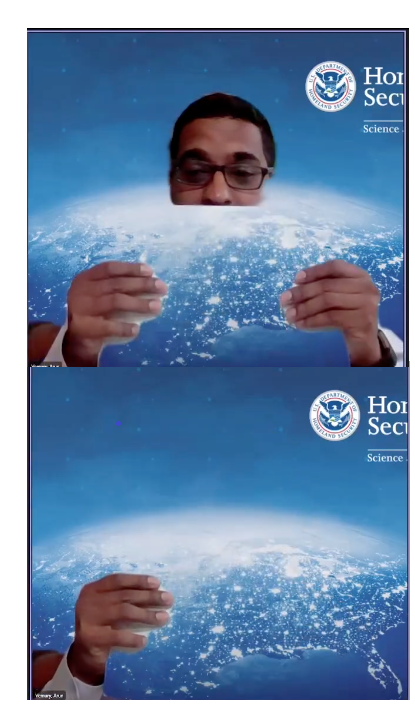

Arun Vemury, the director of the Biometric and Identity Technology Center, part of the DHS Science and Technology Directorate, demonstrated how this might be a problem using a piece of paper. The software in his video conferencing app is programmed to replace anything that's not a face with the preselected background, "But at a certain point," as he covers his face, Vemury noted, "The camera has difficulty realizing that's even my face anymore" and blanks out everything. (See image at right.)

Arun Vemury, the director of the Biometric and Identity Technology Center, part of the DHS Science and Technology Directorate, demonstrated how this might be a problem using a piece of paper. The software in his video conferencing app is programmed to replace anything that's not a face with the preselected background, "But at a certain point," as he covers his face, Vemury noted, "The camera has difficulty realizing that's even my face anymore" and blanks out everything. (See image at right.)

“There needs to be additional focus on the actual acquisition component of the biometric system,” said Sirotin, “including the quality of the cameras and things like contrast. When you put on a face mask, it really disrupts the local contrasts around the face ... especially when you have a contrast of a very bright white mask against maybe a darker skin tone.”

The rallies are scenario tests, not technology tests. Technology tests, like the ones that the National Institute of Standards and Technology runs on facial recognition algorithms, measure a single aspect of performance: “Think racing cars along the Bonneville Salt Flats to see which is faster,” said Sirotin.

Scenario tests, on the other hand, look at various measures of performance for an entire system in a particular use case— think about figuring out which vehicle might be best for delivering packages in town versus in a rural area. “Different cars may perform better in different scenarios,” Sirotin observed.

To help ensure that facial recognition and other biometric identity systems can be measured to consistent standards when it comes to accuracy across racial groups, DHS is supporting the development of international standards “around how to measure and report demographic performance differentials,” Sirotin said.

Comments