EU Looks Ahead for Space Security

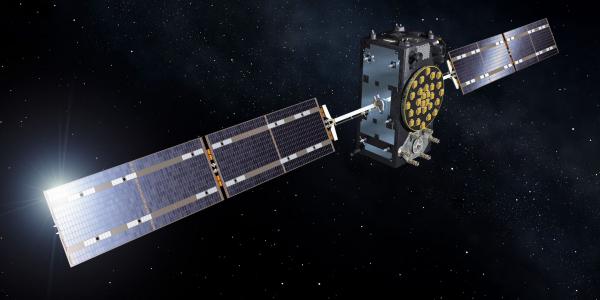

The European Union has established the basis of an organizational structure to safeguard its important satellite assets, particularly those that provide vital positioning, navigation and timing data. As its Galileo constellation has grown in size and significance, the European Union is establishing the necessary organizational infrastructure to build and coordinate a collective effort to secure space against a broad range of threats.

On December 28, 2005, during a time when many people enjoyed the quiet days between Christmas and New Year’s, Europe took a big step forward toward its strategic autonomy in the field of positioning, navigation and timing (PNT). The first of the two experimental satellites for the Galileo program, GIOVE-A, was launched by a Soyuz launcher from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. GIOVE-A transmitted the first Galileo signals in space just 15 days later, on January 12, 2006. The second experimental satellite, GIOVE-B, followed on April 27, 2008. The results of both flights were of great value to the teams preparing the next phase of the program.

With the lessons and real-life data obtained from designing, launching and operating GIOVE-A and -B, the build-up of the operational constellation could begin. In a staged approach, the initial orbit validation (IOV) satellites were launched between 2011-2012, followed by the still ongoing deployment of the full operational capability (FOC) satellites, which started in 2014.

At the same time, but probably not with the same attention by the media and the broader public, the necessary ground infrastructure was built up. Galileo is designed to provide several services for PNT, as well as support for search-and-rescue missions. While all services clearly provide a huge benefit for citizens of the European Union (EU) and worldwide, they also are of great value for government users. The Public Regulated Service (PRS) will provide greater robustness for authorized users when access to other navigation services may be degraded or subjected to malicious interference. However, the duality between civil and government use cases created an additional challenge for this European space program.

To keep the signal in space—meaning an extremely accurate navigation signal sent from the satellites to the receivers on Earth—a giant feedback loop is required between reference points on the ground infrastructure and all satellites. To provide a highly reliable service, not only do the satellites have to carry especially fail-safe and redundant systems like clocks, but also the ground infrastructure must match the robustness requirements.

Critical ground infrastructure is deployed worldwide, mostly on national territory of EU member states. Two Ground Control Centres, one in Germany and the other in Italy, are in place to operate the infrastructure on the ground, fly the satellites and control the satellites’ payload. To maintain the security of the whole system, two Galileo Security Monitoring Centres (GSMC), based in France and Spain, monitor and take action regarding security threats, security alerts and the operational status of the Galileo system. The GSMCs also are responsible for managing user access to the PRS and guaranteeing that sensitive information relating to its use is properly managed and protected. As Galileo PRS will be used in critical infrastructure, ensuring the security of the system also means ensuring the security of its users.

Security is more than just technical, however. To maintain the security for a complex environment like Galileo and to provide security-critical services such as PRS worldwide for use by EU member states, an operational approach embracing the political dimensions is required. Not all kinds of threats can be mitigated technically at system level. Obtaining an overview of what must be dealt with requires a classification. This differentiates between threats, whether they are natural or man-made, material or regulatory, or intentional or unintentional.

Natural threats summarize events such as space weather effects, which include solar flares, solar energetic particles, variations in the solar wind, coronal mass ejections, geomagnetic storms and dynamics, radiation storms and ionospheric disturbances potentially affecting the Earth and space-based infrastructures. Man-made threats include space debris such as nonfunctioning human-made objects in orbit that are no longer in active use. Examples of space debris may be derelict satellites and spent rocket stages as well as fragments from their disintegration, erosion and collisions. Or, the debris could be paint flecks, solidified liquids from spacecraft breakups and unburned particles from solid rocket motors.

Intentional threats include all deliberate interference with space systems, nonkinetic or kinetic, or reversible or irreversible, as well as temporary or permanent in their effects. Typical threat categories are cyber attacks, supply chain attacks or contaminations, electronic warfare, directed energy weapons, high-altitude nuclear explosions and chemical attacks.

The European External Action Service (EEAS) was established on January 1, 2011, to support the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and, as such, to manage the EU’s diplomatic relations with foreign countries and conduct EU foreign and security policy. The service carries out the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), including the Common Security and Defence Policy, which the Council of the European Union developed. The EEAS is in charge of the heritage from the first decision on the security of the Galileo program.

To manage possible security implications for the European Union, Council Joint Action 2004/552/CFSP “…on aspects of the operation of the European satellite radio-navigation system affecting the security of the European Union” was established in 2004, nearly 18 months prior to the launch of the first GIOVE satellite.

As a follow-up, at about the time when the deployment of the Galileo FOC satellite-constellation started in 2014, the council established Decision 2014/496/CFSP “…on aspects of the deployment, operation and use of the European Global Navigation Satellite System affecting the security of the European Union…” (CD-496). A direct result of the CD-496 was that the EEAS installed a dedicated Space Task Force (STF).

Today, Josep Borrell Fontelles, commission vice president and high representative (HR/VP) since December 2019, is in charge of coordinating the external action of the EU and exerts operational responsibilities for crisis management related to the Galileo system. The HR/VP also ensures the consistency of the EU’s external action in the space domain and collaborates with international partners on space security issues.

The special envoy for space (SES) makes the HR/VP’s involvement in space possible and coherent. The STF in turn assists the special envoy by ensuring that the HR/VP’s operational roles with regard to space are fulfilled at any time of the day and year. The force also is in charge of policy tasks and contributes to diplomatic actions.

Regarding outer space, the EU diplomatic initiative 3SOS—for Safety, Security and Sustainability in Outer Space—toward industry, think tanks and academia, space agencies and the scientific community throughout the world raises awareness on threats and builds a common understanding about 3SOS. It contributes to responsible behavior and constitutes a transparency and confidence-building measure by creating a voluntary instrument.

To implement CD-496, the SES and the STF also exert an operational role, namely the GNSS Threat Response Architecture (GTRA). With the support of member states’ experts, they prepare operational scenarios for a council decision on countering imminent threats. The GTRA collaborates with member states, the GSMC and the commission on effective and efficient procedures as well as conducts regular exercises for crisis management.

Handling cyber risks is especially challenging for two reasons. First, cyber attacks are very common today and highly probable because they are cost effective, difficult to attribute and easily deniable. Second, the attack vectors are complex, as an adversary can exploit the supply chain, remote intrusion and local intrusion in any desired combination.

As it stands today, the relevance of space in general seems to be neglected from a cyber perspective. Not a single information sharing and analysis center that the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity has cataloged even partially focuses on the space sector.

Maintaining and improving threat response capabilities requires a collective approach. This calls for increasing the awareness of space as a critical sector because it serves several other sectors, including civil and governmental users. Further, an increased level of trust between member states and EU stakeholders concerning situational awareness and information sharing must develop.

To build a culture that allows the member states to exchange and work on this sensitive topic, a community of trust needs to evolve. The EU and its members already are closely connected via the Internet; they are relying on each other with critical infrastructure such as power grids; the community has a highly interconnected banking sector and shares a common currency. In short, EU members already are sharing important aspects of their sovereignty for their common benefit. This shall translate in the acknowledgement that by establishing EU programs such as Galileo, everyone also works together to protect this infrastructure.

A possible way toward building this community of trust is to also collaborate about security and defense in space matters. Member states could establish common and agreeable points to move forward and reach compromises, if necessary. Moreover, to protect EU shared and interconnected assets, member states also will share the awareness of their vulnerabilities and act together. In an ever-increasing process, this will allow member states to collaborate further in defense and security matters.

The EU must keep pace with an increasingly complex threat landscape that will consist not only of isolated cyber campaigns but also hybrid scenarios that might seek to exploit any internal weakness. That the EU has to progress on its capabilities to defend its common values and its common infrastructure is widely recognized. Improving the EU’s capabilities with regard to security and defense is an especially important aspect when maintaining the protection of Galileo and its users.

These matters will be even more important when CD-496 is extended to the EU space program’s Copernicus, EU-SST and EU-GOVSATCOM. Broadening the scope of CD-496 makes it necessary to apply the lessons learned from the Galileo program.

Galileo is not only technically but also legally complex. On the other hand, the EU has proved its ability to solve complex questions that have arisen on the way, independently from their nature. Since December 2016, Galileo has provided its initial services to more than 1 billion users worldwide, and the European GNSS downstream market generated more than €38 billion in revenues in 2019. Services provided by space infrastructure are ubiquitous for citizens as well as for civil and military users. The EU must move forward to keep its investments protected and the services reliable for the EU and the world.

Carine Claeys is the special envoy for space, European External Action Service.

Comments