Europe's Data Autobahn

While American companies are working to build a laser communications infrastructure and market, Europe already has a laser communications system in operation, the SpaceDataHighway.

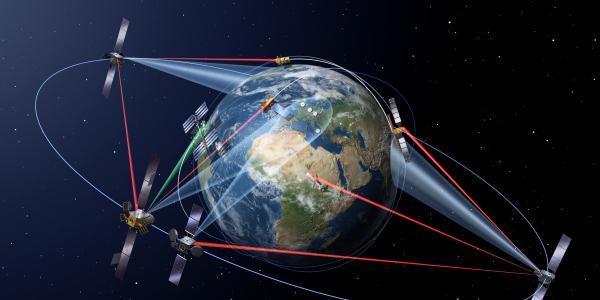

While American companies are working to build a laser communications infrastructure and market, Europe already has a laser communications system in operation, the SpaceDataHighway. The system can transfer customers’ imagery, video, voice and other data from Earth observation satellites, manned aircraft or unmanned aerial vehicles via optical communication geostationary earth orbit (GEO) relay satellites, explains Justin Luczyk, director of business development for Airbus Defense and Space Inc.

Relying on high-precision lasers, the SpaceDataHighway offers a data rate of up to 1.8 gigabytes per second over distances of up to 75,000 kilometers.

The system was built through a public-private partnership between the European Space Agency and Airbus Defense and Space. Germany’s Tesat-Spacecom, with funding from the country’s space administration, manufactured the systems’ laser terminals, Luczyk says.

The European Commission (EC) was the first customer, harnessing the system for its Copernicus program and its series of Sentinel spacecraft. “Our first customers were the Sentinel satellites, which are Earth observation satellites,” he notes. “For [the EC], the big advantage of having laser comms [communications] is twofold. One, by putting your connecting station up in space as opposed to on the ground, it gives the imagery satellites pole-to-pole coverage. And second, the LEO [low-earth-orbit] satellites can take pictures or SAR [synthetic-aperture radar] imagery and get it immediately downloaded back to Earth. They can have near real-time coverage of any images they’ve taken, and they are able to get 50 percent more data off the spacecraft. Historically, they’ve had to wait for ground station flyovers to transfer any data.”

Airbus is continuing to expand the reach of the SpaceDataHighway, Luczyk continues. The first satellite, EDRS-A, launched in January 2016, covers from the U.S. East Coast to India. The second node, EDRS-C, will be launched in July, essentially doubling the capacity of the system. To add coverage of the Asia-Pacific region, Airbus is developing a third node, EDRS-D, through an agreement signed in February with SKY Perfect JSAT, a Japanese telecommunications satellite operator. They aim to have EDRS-D and its three next-generation terminals operational over the region by 2024, Luczyk states.

“EDRS-D has quite a bit more capability than the previous generation because we’re putting three laser heads on it, and they will operate at dual wavelength,” he clarifies. “It opens the ability to serve more customers by operating at two different wavelengths. It also gives us some more flexibility to do GEO-to-GEO crosslinks. Some customers really like the idea of being able to have their data only touch the Earth basically in their home country.”

The addition also will allow aircraft to harness the SpaceDataHighway. “One of the big areas of expansion for us in conjunction with EDRS-D is enabling airborne platforms to be able to do laser communications up to space,” Luczyk notes.

In the meantime, Airbus also is working to build up its market base—to include U.S. users—and is targeting typically underserved communities in space as well as airborne platforms, Luczyk shares. He admits that sometimes customers aren’t aware that the technology exists or that this kind of connectivity is almost unfathomable. “Every customer I talk to on the aircraft side is like, ‘1.8 gigabits per second—that’s incredible,’ because they are struggling with the solutions that they have today,” he states. “But at the same time they have to figure out how to use it, because all of the sudden the data pipe is no longer the operational bottleneck. So that’s led to some really interesting conversations of what else could they do or what conops [concept of operations] that have been completely unavailable in the past are now open.”

A shift in conops could include, for example, elimination of the need for operators in the back of an aircraft. “Why have folks flying on a mission to operate systems on the plane when they could do that from a safe location, thousands of miles away,” Luczyk offers. “So part of what we’re doing is working with the user community, as they’re the ones that figure out how they’re going to use it, and we’re also working with program offices to help them build the long-term requirements around it and help them understand how users are going to rely on laser comms. It opens up the aperture of what is in the realm of the possible.”

Comments