Exploring the Frontiers of Quantum Knowledge

If all goes well with its most recent five-year review, the Joint Quantum Institute will receive a renewal of research dollars next month to continue exploring quantum mechanics and quantum phenomena. The fundamental science could one day lead to revolutionary sensors, electronic devices and computers.

“We’re really pushing the edge of what you can do with technologies,” says Gretchen Campbell, who in April was appointed co-director of the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI). “At the theoretical level, of course, there’s the need to push the frontiers of knowledge.”

The research organization, which marks its 10th anniversary in September, is a joint venture between the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Maryland. “It brings together people studying quantum phenomena across different disciplines in physics. It combines atomic physicists, optical physicists, condensed-matter people and quantum information science,” Campbell explains. “The goal of all of this is to study quantum mechanics and quantum phenomena to see how we can … create new types of devices and sensors and then hopefully … new types of quantum computing and processing.”

Campbell touts the work of her colleague Christopher Monroe, a University of Maryland physics professor who was recently elected to the National Academy of Sciences. “[His] experiments are probably the ones where we will most likely see the direct application—having quantum computers,” she says.

For many researchers as well as the defense, national security and intelligence communities, quantum computing is the holy grail of quantum research. Theoretically, quantum encryption will be impossible to crack. “For quantum computers, one of the main benefits would be encryption and factoring of large numbers, but it would also have other benefits. Say you had this very large database that you wanted to sort through and find important pieces of information: A quantum computer could potentially be much better at that,” Campbell offers.

Quantum computing is tricky in part because a qubit—the quantum version of a computer bit—can be the equivalent of a one, a zero or both simultaneously. Furthermore, qubits can become entangled so that whatever happens to one happens to the other, regardless of how far apart they are. A quantum computing device must create and maintain these quantum connections to have speed and storage advantages over any conventional computer. But so far, harnessing entanglement for computation only works when the qubits are almost completely isolated from the outside world. Isolation and control become much more difficult as more and more qubits are added. As the JQI website explains, “As quantum systems are made bigger, they generally lose their quantum-ness.”

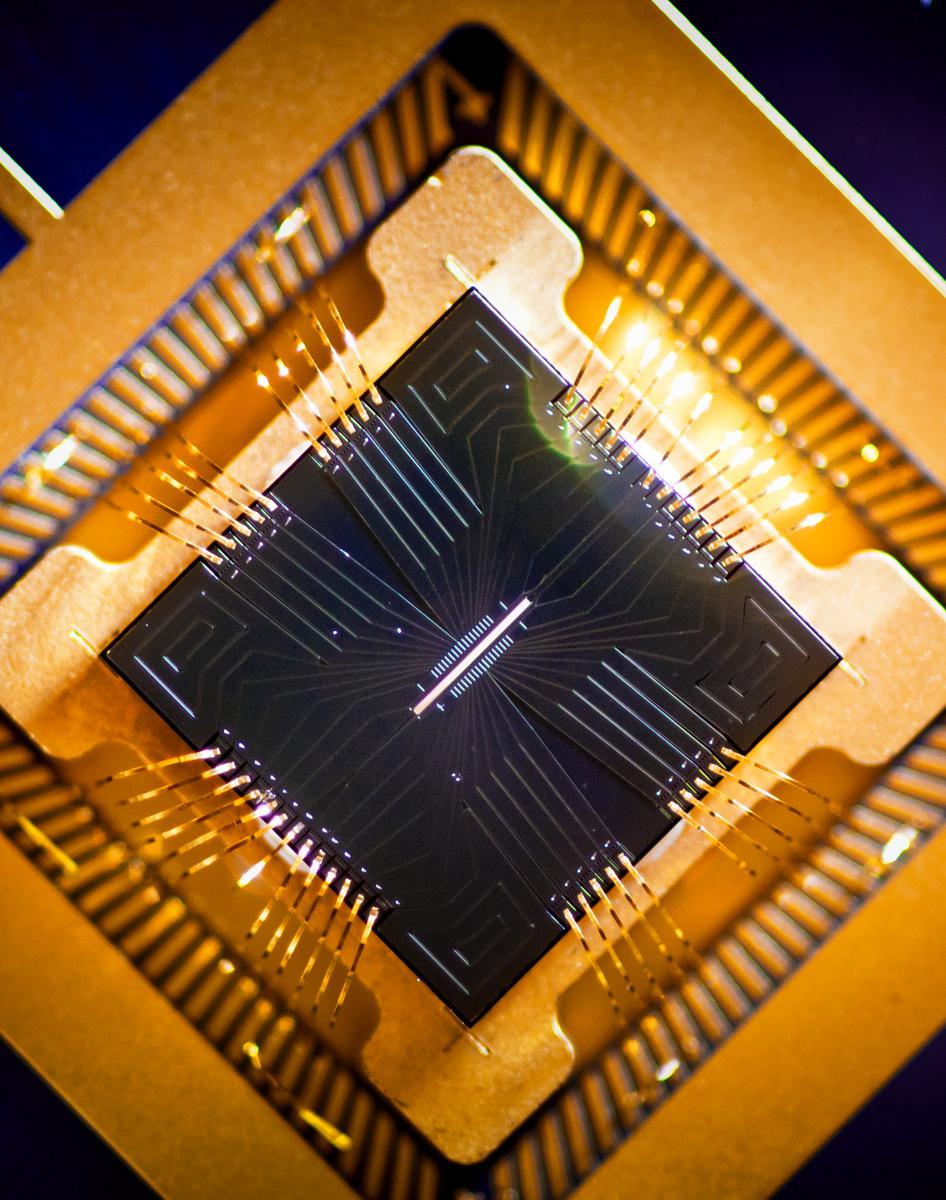

Keeping the qubits isolated and under control requires an ion trap. The goal is to capture as many ions as possible to increase computing power. “[Monroe] has these very exciting experiments where he has trapped ions, and he is showing how you can do qubit operations with these trapped ions with the hopes of building a scalable quantum computer,” Campbell offers. “Right now, he has these chains of trapped ions. He has only a few ions. In order to do quantum information processing, you would need many more qubits than that. The hope is that he can … scale it up to thousands and thousands.”

In addition to quantum computers, the JQI researchers are working on other kinds of quantum sensors and devices, which could be important for various capabilities such as secure communications, optical sensors and improved navigation. Particularly, the development of quantum sensors and communication could be significant for national security and defense. “There are many types of quantum sensors,” Campbell offers, citing optical sensors that measure light at the individual photon level. “The hope is that they can be much more precise. By taking advantage of quantum mechanics, you can take measurements that are less susceptible to noise.”

One example of a quantum sensor already in use is the superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID). “It’s this fantastic magnetic-field sensor that’s taking advantage of the quantum mechanical properties of these superconductors,” Campbell elaborates. SQUIDs measure magnetization of materials and magnetic fields with astonishing degrees of accuracy. They are used to produce MRIs and to detect oil and minerals.

In a similar vein, Campbell’s own research includes experimenting with ultracold atoms. In this case, ultracold is somewhere in the vicinity of minus 459 degrees Fahrenheit. The mind-blowingly frigid atoms form a superfluid, which behaves like fluid with no viscosity or resistance. In a 2014 Nature article, Campbell and her team described using a superfluid made of 400,000 sodium atoms cooled to the point of condensation so that they formed a quantum matter known as a Bose-Einstein condensate.

The atoms of the condensate reside in a doughnut-shaped trap that is slightly bigger than a human red blood cell. A focused laser beam intersects the ring trap and is used to stir the quantum fluid around the ring, creating a current. Because the superfluid is not affected by friction, it does not continuously speed up. Instead, when the stirring reaches a critical rate, the fluid jumps from having no rotation to rotating at a fixed velocity. “We would be taking advantage of the quantum properties to create a sensor that was more precise than a conventional or classic sensor. We’re trying to create circuits that actually behave in ways analogous to SQUIDs. In our system, the analogous circuit to a SQUID would be a rotational sensor,” Campbell offers.

She also is conducting an experiment with strontium atoms for quantum simulation. Conventional computers simply do not have the processing power to replicate certain quantum phenomena. Therefore, scientists use a controllable quantum system to study more complex quantum phenomena and gain insight into the behaviors of elaborate material. With just 30 or so qubits, researchers can study ordering and dynamics of a so-called many-body system, which involves lots of ions. “In the future, make that a few hundred qubits, and there’s simply not enough room in the universe for all the memory required to do the calculation,” says Monroe in a JQI article.

“The idea with these experiments is to understand complicated condensed-matter materials. As it turns out, using these ultracold atoms, you can create systems that can simulate the behavior of more complicated materials,” Campbell reports.

In the future, she adds, the research could lead to new kinds of synthetic materials. “For example, some people are trying to come up with high-temperature superconductors. Room-temperature superconductors could allow you to have improved efficiency in the electrical grid and things like that. That’s very far down the road,” Campbell cautions.

All fellows at the institute, about 30, conduct experiments. About half the fellows come from NIST and the rest from the university. Campbell co-chairs the JQI with fellow Steve Rolston. Because she is new to the position, they still are ironing out their co-chair duties. “I’m learning the ropes. We tend to do things in a collaborative manner and make decisions together,” Campbell says.

The JQI has an annual budget of about $7 million, which has not grown much over the past 10 years. Its first-year budget was $6 million. Recently, the organization has been focused on its five-year review process, which should be complete next month. University personnel had finished the grant-writing process just before Campbell was appointed. “I was lucky,” she quips.

Campbell began her association with NIST during a summer program when she was an undergraduate at Wellesley College. For her first project, she was paired with researchers studying laser cooling and trapping, a group in which she is now a permanent staff member. Her work involved an optical tweezer, which uses a focused beam of light to create small, micron-size particles. Optical tweezers are useful for biological applications. “People have done experiments where they attach little beads to DNA and then use these optical tweezers to stretch out the DNA or measure them,” she reveals.

During her second summer at NIST, she worked on ultracold atoms. “I came down, did the research, loved the environment, loved the science and decided that was what I wanted to do,” Campbell recalls.

Comment

love & respect of quantum

love & respect of quantum knowledge- research

Comments