Eyeing Next-Generation Biometrics

The FBI is on schedule to finish implementing next-generation biometric capabilities, including palm, iris and face recognition, in the summer of next year. New technology processes data more rapidly, provides more accurate information and improves criminal identification and crime-solving abilities.

The Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS), which was launched in 1999, is the largest biometric database in the world, housing the fingerprints and criminal histories for more than 70 million subjects in the criminal master file, according to the FBI website. The database includes the fingerprints from 73,000 known and suspected terrorists processed by the United States or international law enforcement agencies that share information with the FBI. The average response time for an electronic criminal fingerprint submission is about 27 minutes, while civil submissions can take 72 minutes.

The FBI has been incrementally replacing the system with Next Generation Identification (NGI) technology and will officially close IAFIS next year. NGI is a $1.2 billion program run by the agency’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division, Clarksburg, West Virginia. “The plan is that as we go along, we’re replacing pieces of IAFIS. In the summer of 2014, IAFIS will be decommissioned, and NGI will take all of the capabilities,” says Kevin Reid, NGI program manager, CJIS.

NGI includes seven increments. The first step—increment zero—simply replaced older computer systems with new, high-definition workstations that make it easier for fingerprint examiners to do their jobs more quickly and accurately. Increment one introduced new fingerprint matching algorithms that are scalable, meaning officials can more easily increase the number of searches. “Increment one has been up and running for two years, and we’re finding it is more accurate. It increased the overall accuracy substantially, and in doing that, it was able to replace fingerprint examiners,” reports Bill McKinsey, NGI section chief, CJIS.

Reid adds that when the new algorithms were implemented, the FBI compared them to the previous process. “We did a side-by-side operational analysis for the first five days, and we actually found that the new system identified 910 candidates that would not have been identified on the old system. The majority of those were violent crimes,” Reid reveals. “We’ve already processed 185 million transactions, so it’s working pretty well.”

Increment one also enhanced the ability to handle a surge in searches. “On the fingerprint system, the problem is always that all at once someone wants to do an extraordinarily large application in a short period of time,” McKinsey asserts. He cites one example in which users wanted to handle three times the number of transactions for an entire week.

To solve the problem, developers used a matrix. “We’ve designed a matrix, so if you want to handle large numbers of increases in the total number of fingerprints each day, you can add more strings. You can visualize that as the columns of the matrix. You can just add two or three of those, and you’ve increased your volume very, very quickly,” McKinsey explains. “If you want it to go faster, you add more rows to each one of those in the matrix arrangement. It gives us more flexibility.”

The NGI also includes mobile fingerprint scanners. “We’re finding that the mobile fingerprint scanners are extraordinarily popular with law enforcement. If they had the money, every officer would have a fingerprint examiner in the car by the close of business today,” McKinsey suggests. “The big challenge is just getting the scanners into everybody’s hands. There are cases where some law enforcement agencies are having to decide whether they’re going to be able to pay their uniformed officers. That makes it very difficult to get new fingerprint scanners into operation,” he says.

State, local and tribal agencies must purchase the scanners themselves. Still, they are being fielded relatively quickly. The scanners are used in 14 states so far, which is ahead of schedule. “They’re doing it even faster than many of them predicted they could, but not as fast as many of them would like to,” McKinsey adds.

The mobile scanning device is part of the Repository of Individuals of Special Concern. The system allows searches in less than 7 seconds for wanted persons, registered sex offenders, known or suspected terrorists and other persons of special interest. Officials in the field use the device to scan a person’s fingerprints and receive either a red, yellow or green status, indicating a highly probable match, possible match or no match at all.

“We’ve done almost 900,000 transactions on that system today. Every day’s a new success story,” Reid says. If officials first search their state database without a hit, they can then search the nationwide database, allowing law enforcement agencies in Georgia, for example, to identify a suspect wanted in Florida, he explains.

Increment three, which includes latent fingerprint and palm print identification capabilities, was introduced earlier this year. Latent fingerprints are those extracted from crime scenes. While the FBI has been identifying such prints for a number of years, the NGI makes the process faster and more accurate. Reid cites a case in which officials in Florida used the new system to run prints that had come up empty under the old system. “With the new system, there was actually a hit associated with an individual from Texas and the crime associated with that was a murder. It’s still an active investigation, but they believe they’ve identified the murder suspect who has now been arrested in Texas. They found the location of that individual where they wouldn’t have before. That’s an example of the latent capability that has three times the accuracy of the old system. So there will be a significant amount of cold cases solved,” Reid predicts.

Palm print identification is a new capability that is not yet widespread. “A relatively small number of states and cities have palm print systems. It’s operating, but it is running against a relatively small database, so we’re working with the states and cities to move palm print data in here to our database. We won’t realize the full benefit of that palm print system, even though it’s fully operational, until such time as we grow that database quite a bit,” McKinsey reveals. Still, he says palm print identification will likely prove indispensable because research shows that, “An enormously high percentage of the prints left at crime scenes are palm prints.”

Increments zero through three have been implemented. Increment four provides a number of new capabilities, including facial recognition. NGI program officials must coordinate closely with law enforcement agencies across the country on everything they do, but that is especially true for facial recognition. “If we make a change, law enforcement has to make a corresponding change. In the case of facial recognition, lots of states are already doing it, and we have to make sure that we all have the same set of policies in place and that we’re all operating it the same way,” McKinsey offers.

Increment four also provides a capability officials call rap back, a reference to rap sheets. The new capability, which is in final development and was being beta tested in June, allows organizations to monitor people in sensitive positions—police officers, school teachers or medical personnel, for example. Previously, organizations were limited to doing a background check, including fingerprints, for new employees. “When they hire them now, they will have the opportunity to enroll those people for continuous scrutiny in the fingerprint system. When their fingerprint comes through for the background check, it will be added to the file here, and everything that comes in here in the way of a criminal transaction will be run past those prints. In the event there’s a hit, the organization that has subscribed to that service will be notified of the hit,” McKinsey explains.

To illustrate the point, McKinsey offers a hypothetical example in which a new school teacher in Texas is enrolled in the system by the school. That teacher spends some time in Las Vegas, engages in some questionable behavior and is fingerprinted by law enforcement. In the past, only officials in Las Vegas would be aware that anything had happened. But now, the teacher’s employer could receive a note.

Additionally, increment four includes up-close photographs of tattoos, scars or other identifying markings. Currently, IAFIS can accept mug shots. The Interstate Photo System will allow users to add other photographs to previously submitted arrest data and to submit photographs in bulk formats. The system also will allow for easier retrieval of photographs.

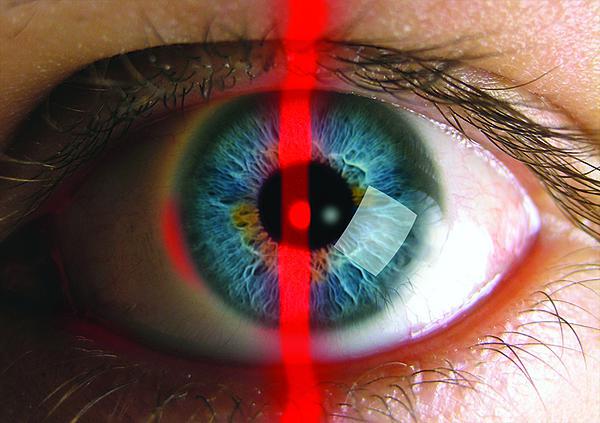

Increment five is a pilot project for using iris recognition. Program officials are evaluating the business case for expanding iris recognition to the national level. It is not yet clear how useful iris recognition will be in criminal investigations. As Reid points out, “There aren’t a lot of irises left at a crime scene.” There are, however, a lot of photographs taken at crime scenes, which could include pictures of eyes that could potentially be matched against the iris recognition system. “The iris pilot started about a year ago in concert with our partner, the National Institute of Standards and Technology. We’re working with several different agencies to bring in their iris data,” Reid discloses. He adds that the two biggest users will likely be the Defense Department and the prison and jail systems, which use iris data for keeping track of prisoners.

The NGI program is more than 80 percent developed and more than 70 percent implemented. It will be fully implemented next year. The final increment will be a technical refresh, which will go on as long as necessary. “The program is on-scope, on-schedule and on-cost. Those are three of my favorite words,” McKinsey quips.

Comment

Largest biometric database?

Calling any system the "largest biometric database" is fraught with complications. Does it contain the largest number of subjects, individual images, on-line vs. off-line, or criminal vs. non-criminal? By most standards the "worlds largest" biometric database is the Indian Aadhaar system which has enrolled around 400 million individuals with finger, iris, and face biometrics. The US DHS Ident system contains approximately 130 million subjects. While the FBI may have the world's largest criminal biometric data base, it would be hard to make the claim it's the worlds largest.

Comments