Army Teaches Soldiers New Intelligence-Gathering Role

|

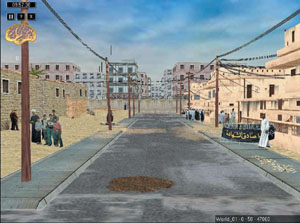

| The U.S. Army’s Every Soldier a Sensor (ES2) simulation uses computer game technology to teach soldiers how to perform as if they were sensors in an intelligence network. This screen shot shows a typical street scene in an urban environment where a soldier may have to interact with the local populace or deal with suddenly introduced situations. |

Cartoon game expertise trains individuals on how to be nodes in a network.

The U.S. Army is turning to commercial game technology to teach soldiers how to function like sensors in the network-centric battlespace. An application derived from popular computer-game software is teaching Army personnel how to think, act and respond like intelligence sensors in a network.

Part of the Army’s transformation is the creation of an all-encompassing intelligence network that relies on individuals to provide vital information on all aspects of situational awareness. But while soldiers know many items of information that must be reported to higher echelons, they are not always aware of all of the key facts and observations that should be reported to the intelligence network.

This new simulation teaches them how to operate like a sensor and how to seek additional information as a situation develops. In effect, it works as if it were an artificial intelligence teaching tool. But its targets are the human minds that make up ground forces, and its mechanism is a simulation designed to draw its students into the world of investigation and response.

“This simulation teaches more a cognitive skill,” explains Maj. Daniel P. Ray, USA, modeling and simulations officer for the Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, G-2, the Pentagon. The task of reporting intelligence information is not new, but the conditions have changed drastically, the major continues. Soldiers must be taught how to observe elements that were not part of previous intelligence-gathering criteria.

“It really is inculcating an idea—a concept in soldiers’ minds—that they have a role to play, that they are important to the architecture and that they are not just toting a rifle out in the streets,” Maj. Ray says. “There is interaction with civilians, and sometimes a civilian can give you information that is important. Then you need to pass it along—or take action.”

The Army had several reasons for choosing commercial game technology to build an intelligence trainer. To focus on the concept of every soldier a sensor, or ES2, officials wanted to present the concept in a way that not only would keep their interest but also would impel them to advance their skills through repeated use. The G-2 office wanted to develop a simulation that would be practiced eagerly by the soldiers, instead of imposing a regimen that they would accept grudgingly.

The Army tapped the Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), which is a collaborative effort among the Army, the University of Southern California and the entertainment industry. The institute had an idea for a technical proof of principle in an effort that it called Weblets. This was a Web-based downloadable training tool that would instruct users in only one or two simple tasks. The institute was aiming to build a simulation in 12 weeks for $500,000 or less. So, Army G-2 offered to provide the theme of ES2 for the proof of principle.

The institute subcontracted to Warner Bros. Online, Glendale, California, which normally designs games based on the company’s well-known cartoon characters. The result was a beta version that stayed below the funding ceiling but exceeded expectations, according to Maj. Ray. The high fidelity of this ES2 simulation, known as ES3, led to the Army’s decision to withhold placing it on a public server as the Army did for its popular America’s Army game. The ES3’s content is so realistic and useful that authorities do not want it to be accessible to Iraqi terrorists and insurgents. Engineers are working on a sanitized version that could be made available to the public.

The driver behind the development of this simulation was lessons learned in Afghanistan and Iraq. These two wars provided a broad-based introduction to networking technologies that link individual warfighters. However, this networking was not as successful as it could have been, and part of the reason was that soldiers did not know how to exploit it fully.

“We had lots of patrols going out, but very few reports coming back,” Maj. Ray relates. “And, some of their reports were not going into the system.” Collin Agee, director, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance integration at the G-2 office, notes that, out of 400,000 patrols conducted in the Iraq War, only 6,000 reports reached brigade level. The G-2 assessment was that rear-area soldiers were not trained to do reporting and were not focused on situational awareness input.

Maj. Ray concurs. “That led to a realization that the soldiers were not trained in observing techniques and in reporting standards and procedures. The soldiers just were not trained for this complex asymmetric environment,” he concludes.

Agee notes that the training audience for this simulation is every soldier in the Army. Certain elements of the Army, such as long-range reconnaissance scouts, traditionally have been good at reporting. Now, reporting is becoming a core competency for all Army personnel. For example, logistics personnel more than ever are exposed to conditions and situations that feature information that is needed up the chain of command.

This is an issue that becomes even more vital beyond technological advances. U.S. forces in Iraq are fighting an asymmetric urban war in conditions that place a greater emphasis on human intelligence (HUMINT). One source of that human intelligence is the body of U.S. soldiers who patrol the streets. These soldiers have assumed a role similar to that of police officers on the beat when it comes to situational reporting. One key element of being an effective beat police officer is to develop an experience base, especially in disciplines such as change detection. This simulation aims to help that development.

Maj. Ray points out another problem that emerged from the streets of Iraq. Often, when a soldier did not see any action taken on a report that he had filed, he would be less likely to report that same kind of activity in the future. Not only is this counterproductive for the flow of intelligence, but it also may represent an inaccurate assessment of the situation, as action may be underway but out of sight of that soldier. Part of the concept of ES2 is that the individual soldier is important, whether he realizes it or not.

One ES3 element incorporates information operation (IO) scoring. If, for example, a participant shoots a child, that would generate a bad IO score. On the other hand, buying some food from the child would generate a better IO score in that the youth might be willing to provide information to the U.S. soldier.

The skills that this simulation imparts also can help soldiers survive an urban warfare environment. One example of a very basic observation skill is to recognize a menacing scene when an area has become “too quiet,” to quote an old cliché. The local populace suddenly may have disappeared or retreated into the shadows amid reduced activity. Soldiers need to be trained to recognize these symptoms of a potential ambush, and the simulation addresses that with a level known as “an unusually quiet day.”

The simulation currently offers 10 different levels that allow soldiers to explore a range of scenarios for various types of patrols and encounters in an urban environment. In addition to the quiet-day scenario, levels include “the market revisited,” “hunting for explosives,” “terrorist café” and “tension rising,” for example.

A soldier would begin the simulation by receiving a briefing for that patrol. The briefing includes a map, a given threat level and the degree of hostility that the soldiers may face. When the patrol begins, the participant sees images of people and objects embedded in a three-dimensional (3-D) environment.

The participating soldier has the man-in-the-street perspective as he “walks” down the realistic-appearing road. Two-dimensional images of people are placed in various locations, and those images turn as the participant walks by, which creates a 3-D effect. This provides considerable savings in processing power and bandwidth, Maj. Ray notes.

The soldier can react to the presence of these people in several ways. He can ignore them; he can take a photograph of them; he can talk with them; or he can shoot them on sight, although that probably would cost him points in his IO score.

In one scenario, the soldier, on patrol to find unexploded ordnance, talks to a group of men standing on a street corner. They ask him if the Army can clean up the local soccer field, which tells the soldier that they are looking to set up a local soccer club. The soldier walks to the soccer field and discovers that it has unexploded ordnance sitting in it. The soldier reports this discovery and receives both IO points in his score and plaudits from the simulation’s commanding officer in a typical Army manner: “Good job, soldier—you don’t have to make your bed for a week.”

After the participating soldier has played a level, he then undergoes a patrol debrief as he would in a real post-patrol situation. The simulation provides a critique that includes how the soldier might have missed some vital points of information or objectives. The soldier accesses an after-action report for a full assessment of the success of the mission.

The iterative process allows soldiers to go back into the simulation to try to improve their scores. As they qualify for certain levels, they can advance to higher levels. This can motivate soldiers to stick with the game and improve their proficiency.

The ES3 approach is different from typical game playing, Maj. Ray points out. “In the gaming world, I get my score and I’m done. In the training world, you have to know and understand what you did wrong,” he explains. “Without a review or feedback, it’s not training. It’s just a waste of time.”

Unlike America’s Army, ES3 is offered for download from a dedicated Web site limited to Army personnel. Its distributed nature translates to a file size of only 43 megabytes, which allows a user to download it virtually anywhere. Hosted on a secure server, it also has an upload capability for future modifications. Registered users can post their scores on a bulletin board for comparison, which allows others to monitor the progress of individuals or units. Maj. Ray allows that the beta version of the simulation already has generated considerable feedback.

“This is truly spiral development,” he says. “Every two weeks, I would get a new version with new levels.” Beta testers include personnel at battle simulation centers and at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

The biggest challenge in bringing this system to reality was the Army bureaucracy, Maj. Ray declares. “It took six months from the time its white paper was written to the time that someone agreed [to go ahead],” he says. This compares to less than three months to develop the simulation. “There is a huge cultural philosophical issue with using commercial game technology to build a simulation or training tool—‘games are entertainment; they can’t be training,’” he recites.

Once they had the funding, Army officials worked with the ICT on defining the game. Experts from the institute joined them in meetings with HUMINT and doctrine officials at Fort Huachuca, and then they interviewed veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq operations at Fort Benning, Georgia. The experiential vignettes from Fort Benning soldiers were the critical pieces of the simulation, Maj. Ray offers.

All of these elements were combined with the 3-D environment from ICT’s combat game Full Spectrum Warrior program to produce ES3. The software that constitutes the game engine comes from a French company, which created some accreditation problems. But it was the “best of breed” for what the Army was trying to accomplish, Maj. Ray relates, so it was adopted for the system.

Agee allows that he would define the simulation’s success by soldiers’ wanting to download it voluntarily just because they enjoy using it. G-2 officials hope that Army units incorporate it into the program of instruction or collective training. A future iteration may incorporate terrain data from a specific location to allow personnel operating in that area to immerse themselves into a situationally realistic simulation.

The G-2 office has had discussions with the U.S. Military Academy at West Point for hosting ES3 in its post-beta form. The simulation currently is hosted on a secure server at Warner Bros. Online. The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), Fort Monroe, Virginia, is the lead for ES2 training. By the turn of the fiscal year in September, TRADOC will decide whether to accept it or discard it.

Web Resources

U.S. Army G-2: www.dami.army.pentagon.mil

ICT ES3 Project: www.ict.usc.edu/disp.php?bd=proj_games_slim_es3

ES3 Access Information E-Mail: Daniel.Ray@us.army.mil

Comments