Building Geodata Block by Block

Researchers are preparing to release technology designed to overcome the challenges of coping with large amounts of geospatial data. The Web-based system makes it easier to layer blocks of information, allowing a wide variety of users to quickly understand and share complex data sets.

The National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Geospatial Building Blocks (GABBs) project is creating a system for hosting, processing, analyzing and sharing geospatial information. The system is built on HUBzero, an open source platform developed at Purdue University that lets individuals build feature-rich websites to advance research and education.

GABBs offers the ability to layer different kinds of geospatial data and see how they interact. Such data can include maps, aerial photos, satellite imagery, sensor output and virtually anything able to be georeferenced or located on a map. The data used can range from field-level crop yields and local population densities to regional weather, the flow of trade across national borders or the kinds of crimes perpetrated in particular areas.

Program officials say the geospatial data building blocks will lead to the development of a variety of Internet-based tools for sharing, probing and presenting geodata in ways that can help address pressing issues in the United States and around the globe. The effort is supported by a $4.5 million, four-year grant from the NSF’s Data Infrastructure Building Blocks (DIBBs) program, which aims to improve data science by supporting the development of tools, technologies and community knowledge. Projects supported by DIBBs involve collaborations between computer scientists and researchers in other fields.

“We’re putting out tools that make dealing with complex data—for example, remote-sensing data or satellite data—very easy. People don’t have to download any software. They just go into a Web portal and start using it,” says Carol X. Song, a senior research scientist at Purdue and the GABBs principal investigator.

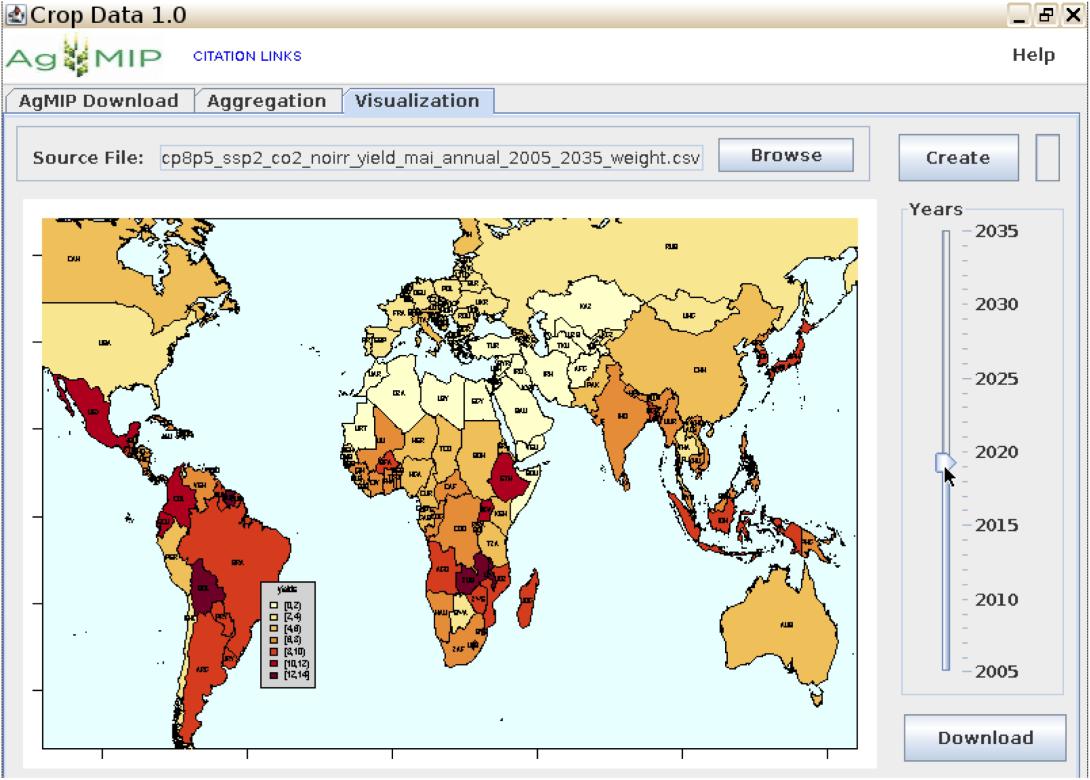

The project offers quick and easy access to the data needed for research. For example, one major endeavor involved scientists studying climate data. Most were modelers with different ways of using variable data to drive their models. “They were comparing and then running scenarios for different crops, different agricultural practices, like irrigation, and then they produced this big data archive. The archive is open, but it turns out it is not trivial to use it,” Song explains. “First of all, the data is only available through a very specific protocol, so you need to know the tools in order to access the data.”

Song’s team helped the scientists create an online tool to access the information by selecting well-defined parameters of interest—specific crops, for example—and then using a particular model to receive only the data of interest. “That helps them retrieve the data and, using their own aggregation maps, to aggregate the data for certain regions without doing all the processing themselves,” Song elaborates. “It’s all done on a remote server, a powerful computing cluster, and they just get the results back.”

Without DIBBs, dealing with the complexities of geospatial data can slow scientific research significantly. “It’s a major hurdle for a scientist to deal with the spatial data,” Song says. “Researchers have to spend six months to a year to straighten out these data sets before they can do anything. We’re helping them by using our building block software to make the data conversion, data import and export much easier to use.”

The GABBs project has involved scientists from a variety of fields. They include social scientists, economists and hydrologists, who study the flow and quality of water. GABBs likely will benefit scientists studying Southeast Asia’s Mekong River, reveals Robert Chadduck, who holds multiple titles at the NSF, including program director, data and cyber infrastructure. “There actually are efforts underway, including with the State Department, to make the tools available in Vietnam, effectively at no cost. They can use it for doing things with the Mekong River, where the tools, the visualization, the software can be a commodity resource for geospatial work broadly,” Chadduck says.

The technology also helped researchers learn some facts about Chicago. “The city of Chicago puts out a lot of data sets for public consumption, like spreadsheet data, crime data and traffic accidents. We were working with some of those data sets to see how we can help places like that,” Song reports, indicating that it was an informal effort. “With our tools, we showed that we can take in their data sets, show the data sets on a map, and then people can start querying the data. They can see in the last year the severe crimes—bank-related crimes, for example—and people can easily filter those just like they filter in a spreadsheet program, with those spots showing up on the map.”

Teachers and students also may find the technology useful. “We’re hoping to build on this and do more in the educational domain, especially the high schools. The tools we have are unique, and this would expose the high school students to very high-end computing facilities without the barriers. They can use it and get a sense of what these resources can do and then eventually, perhaps, build their own,” Song says.

The research team touts the technology’s flexibility, and Song says the team is eager to work with a variety of users, potentially including the Homeland Security Department and the Defense Department. “In terms of homeland security or others, if they have the need to quickly disseminate data ... and make it easier to understand, those are areas we can help. I would love to have some connections to people who have those data sets,” Song says.

Chadduck notes that making the technology available to a wide array of users is part of the point for the GABBs project. “The development, the software, the visualization tool, the data management tools are purposely built to be repurposable,” he says. “As building blocks, the GABBs products are intended to be detachable. If you’re interested in the data visualization piece, if that fits well in your environment—potentially in a national defense, national security environment—there’s no constraint on it being used. If you see the advantages of the data management architecture, that also could be detached from some of the other pieces because each is a building block.”

The building block concept is the project’s central feature. “The term building blocks is purposeful in the sense that the developed pieces are intended to have other building blocks around them, on top of them, underneath them,” Chadduck states.

The plan is to release an initial capability in October, the project’s three-year anniversary. That will be followed by a second release about a year later.

Song’s team has developed a website, mygeohub.org, where the open source software can be released. “People can download and set up their own site, but they can also come to [the site] to start using it right away,” Song points out.

The first release will include a set of basic support tools. Users can study their data without having to do any programming first. “They can input their data into the tool and then see the data in a geospatial context and start manipulating and creating specific views to share with other people. They can also create their own modeling tools that use geospatial data and have the tools hosted on My Geo Hub,” Song explains.

The team still has work to do before the second release. “People know that with websites, when you upload, you can’t really go very large. If you go to 10 gigabytes, that takes a while, and some sites just break,” Song offers. “We are dealing with data of 100 gigabytes at least, and it’s definitely going to be larger as time goes. Very few people want to analyze online a terabyte of data. That’s an issue.”

But she already has possible solutions in mind. “Depending on the processing requirements, we could connect to large computing clusters. There are ways to subset the data and select only the data users are interested in so we don’t have to jam all that data into the Web server,” she suggests.

She also intends to ensure the GABBs software is interoperable with other NSF-developed technologies. The GABBs team recently started working with HydroShare, which aims to provide new ways to create and apply hydrologic knowledge. The team also collaborates with the integrated Rule-Oriented Data System, also known as iRODS, another initiative supporting distributed data repository technologies.

Chadduck describes GABBs as a “stellar project in the context of the National Science Foundation’s cyber infrastructure development efforts.” The opportunity that GABBs presents is to “significantly leverage the infrastructure and the previous developments and the architectures emerging in the HUBzero environment” and to “specifically apply them to the challenges and the opportunities of the geospatial data community,” he says.

Comments