NASA's Communications Challenge

Building on the success of private industry cargo, launch and commercial crew services, NASA is betting on the commercial satellite industry to meet its future communication needs. It is turning to a service model for fixed satellite services in low-Earth orbit to support its various missions and later is planning on using mobile satellite services. What stands in the administration’s way, however, is a lengthy regulatory hurdle. NASA must obtain spectrum regulatory recognition for satellite-to-satellite operations from the world’s governing body, the World Radio Conference, which only meets every four years.

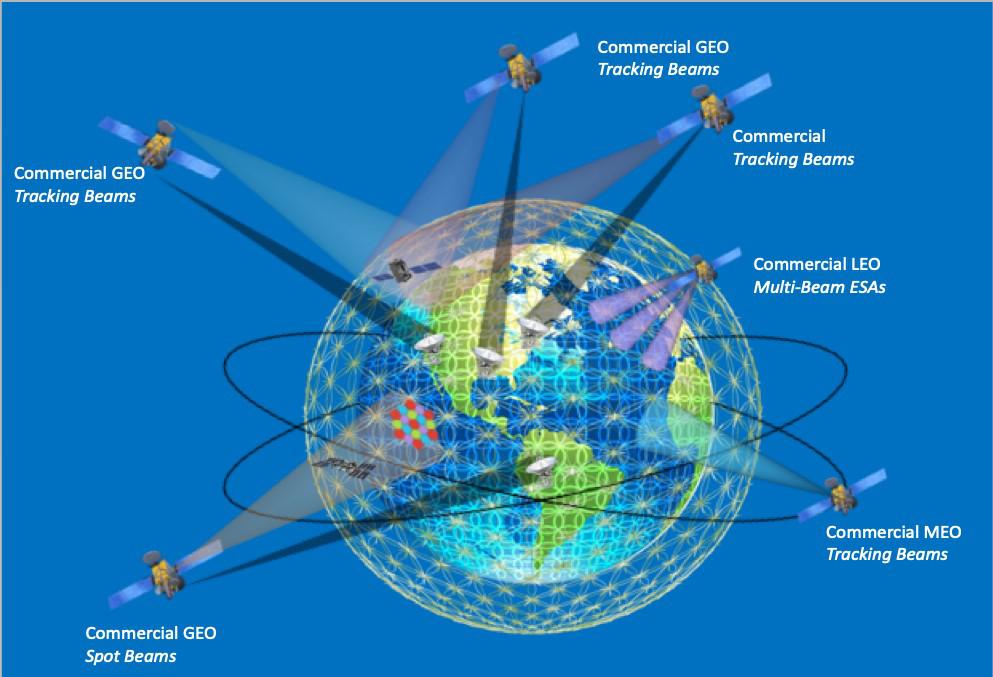

NASA hopes to be able to replace its space-to-ground Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System, known as TDRSS, which provides data relay from space stations in low-Earth orbit to TDRSS ground stations. The administration must achieve approval for a satellite-to-satellite construct from the World Radio Conference (WRC) to even be able to depend on such advanced commercial offerings. And correspondingly, companies would not have much of a business case to offer such services without this “protected status” declaration from the WRC that enables the companies to avoid having to operate on a less dependable noninterference basis.

“The big challenge for us is going to be the regulatory challenge,” says Eli Naffah, project manager, Communications Services Project (CSP), NASA. “That’s the process we have to go through because if you don’t have a treaty that says you can use it globally for that purpose on a noninterference basis, it’s not going to work because there will be interference. And of course, if you are a company in the fixed-satellite service (FSS) industry, you’re concerned that if you are doing space-to-space [relays] it could interfere with your existing business base terrestrially.”

The WRC, which is held by the United Nations International Telecommunications Union, is next conducting its treaty-level negotiations in 2023. Within the United States, the Federal Communications Commission and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration play a role in developing agenda items for the WRC negotiations, as does industry, including through the Mobile Satellite Users Association, which met in March to discuss industry input for WRC 23 and WRC 27.

For WRC 23, the United States will negotiate so-called Agenda Item 1.17 regarding fixed satellite-to-satellite operations in frequency bands 11.7-12.7 gigahertz (GHz); 18.1-18.6 GHz, 18.8-20.2 GHz and 27.5-30 GHZ to obtain a corresponding intersatellite service allocation. In 2019, the WRC decided not to discuss the related mobile-satellite service, or MSS, allocation, and instead slated it for possible consideration in 2027. Parties at the WRC 23 meeting will decide whether or not to include discussion for MSS at WRC 27 under Agenda Item 2.8 for mobile operations in frequency bands 1 525-1 544 megahertz (MHz); 1 545-1 559 MHz; 1 610-1 645.5 MHz; 1 646.5-1 660.5 MHz and 2 483.5-2 500 MHz amongst geostationary and non-geostationary satellites.

“We have an agenda item at the WRC 23 called 1.17, which deals with using fixed-satellite service spectrum for space-to-space communications,” Naffah explains. “That’s important if we want to leverage existing infrastructure that is out there for FSS. We’re working actively with partners in industry and in other nations to try to bring that to fruition so that we can get an allocation, and that would then enable the business case. For WRC 27, we are trying to get an agenda item for the mobile satellite era. We’re working those and it takes a long time. There’s the potential for some optical communications, and that will help, so we are not banking on any one solution.”

NASA is looking for industry and government sector input on WRC 27 agenda item 2.8 and points companies to participate in the FCC’s WRC-23 Advisory Committee. “NASA is seeking to partner with the U.S. Mobile-Satellite-Service industry on development of a mutually agreeable proposal,” Naffah states. “And in the long-term, NASA is seeking to partner with the industry to conduct the necessary spectrum sharing and feasibility studies toward demonstrating the feasibility of satellite-to-satellite operations in these MSS bands.”

In the meantime, NASA is conducting two CSP demonstration efforts with industry, in its hedge that the private sector can meet its primary space communications demand in the future, even though commercial satellite communications (COMSATCOM) capability falls short of NASA mission needs at present. So far, COMSATCOM capabilities have only been built for terrestrial, aeronautical and maritime use, and NASA wants to spur a market for its space operations uses, Naffah notes.

“The approach that we are taking is a little bit different than what the Defense Department has done, in that we are not trying to adapt commercial service to NASA,” the CSP project manager emphasizes. “We are trying to adapt NASA to commercial service. We want to be one of many buyers where it is truly a commercial service, and it is not provided as a unique service to NASA. That’s the goal.”

One of the CSP demonstrations is for assured data delivery capabilities that will support NASA’s launch communications and other time-critical operations. The assured data delivery effort will support the distribution of mission data; tracking, telemetry and telecommand links; navigation, ranging and timing; and networking and security. Such capabilities would mostly be at lower data rates but with very low latency, 24/7 access and bidirectional data flows, Naffah explains.

The second demonstration will examine file delivery and networking capabilities to provide for the return of science data obtained in space. The file delivery and networking demonstration will feature cloud storage and data broadcasting of telemetry and other data to a mission operations center or a remote principal investigator. “Links will typically support larger data file transmission, higher data rates, but can tolerate higher latencies, making it ideal for transport via a ‘store and forward’ or burst mode, if necessary,” Naffah says.

Both demonstrations are tied to NASA’s various mission use cases. For each CSP effort, NASA will examine COMSATCOM performance validation, operational approaches and possible acquisition constructs. “What we’re looking for is the end-to-end operational capability of being able to deliver the data between the interface at the spacecraft and the interface at the mission operations center,” he explains. “And [we need] all of the things that go in between, including the service planning as well as the service execution and service accountability. We want to get a sense of what the acquisition model would be to go out and acquire these commercial services, how much it would cost, how we would do it, what the service-level agreements are going to look like as well as the operational constructs.”

NASA released the CSP solicitations last summer and is relying on long-term, commercial-industry supportive contracting authority—similar to the Defense Department’s other transactional authority (OTA)—that is underpinned by the Space Act of 1958. “They use these contracting vehicles for building partnerships with industry,” Naffah says. “This is not a new authority. It has been a part of the Space Act for a long time. When NASA was created, they gave us pretty broad authority to enter into traditional type contracts and ways of working with industry. Of course, NASA uses the FAR, but why do they have this flexibility? We are really kind of leveraging off of the success we’ve had, and we really are targeting all the NASA mission use cases through this CSP.”

The administration plans to make multiple CSP awards under the OTA-like contracts to COMSATCOM companies this spring and start the demonstrations as soon as possible this year. [Information on NASA’s CSP awards was not available at the time of SIGNAL’s production schedule.]

“What we’re seeing back in their proposals is what the [industry] wants, what they would like to do based on their interest in our capabilities and the services they think they can sell and invest in,” Naffah stresses. “Once we’ve awarded, we’ll see specifically what we’re going to be able to cover and then if there are gaps, then we will have to address those.”

In addition, the administration is looking for secondary COMSATCOM solutions. “NASA is also interested in stimulating additional or enhanced capabilities that could be offered or demonstrated by participants, including tracking and navigational services, direct satellite-to-satellite messaging, demand access services, real-time video services for human spaceflight,” the project manager shares.

Naffah emphasizes that they will draft contracts with favorable language to encourage the COMSATCOM industry further. “The way we structured the demonstrations is that we are giving maximum intellectual property rates to industry,” the project manager stipulates. “That is on purpose to maximize investment on the industry side, make sure that they had skin in the game and an interest in getting this done and that it wasn’t going to be unique to us. The other aspect of it is that we know that they’re going to be competing against each other. That is good for us; it lowers costs. And if they’re able to retain the intellectual property that they generate as a result of these demonstrations, they’ll be in a better position to market themselves and sell their services. In the end, we don’t want to have any hardware or infrastructure. We just want to buy a service. Hopefully, then we can divest ourselves of the expense of infrastructure that we have to maintain today and focus on the things that NASA does well, the science and the exploration.”

NASA hopes to begin acquiring COMSATCOM solutions as early as 2024, and as such, is depending on the demonstrations to inform that formal acquisition process. “As we’re doing the demonstrations, we’re going to start looking at what the acquisition strategy would be and start planning the potential to go out with the acquisitions for commercial service,” Naffah suggests. “We’re not going to wait till the end of the demonstration to start planning how we would bring commercial services on to NASA missions. We’re going to start that planning as soon as we start the demonstration and start feeding that information that we are getting from the demos.”

In addition, the demonstrations are also meant to shift NASA’s culture to believe in the verity of COMSATCOM solutions. “Being able to provide reliable, robust commercial services and convincing and getting confidence built within NASA is going to be a part of it,” Naffah notes. “Part of the demonstrations is to bring that out and show the missions what they can expect.”

NASA’s demand for communications, however, is a long-term endeavor and has to address evolving technologies. “One of the issues is the longevity of the missions,” he observes. Typically, you’ll have a mission that is originally planned five years, and then it goes into an extended mission. NASA tries to get everything out of it that they can. But it is hard to build a service contract for 50 years. And when you have a robotic spacecraft in orbit, you can’t just change out the comms system. So, how do we evolve with the industry that is changing so quickly? That’s going to be a challenge.”

Comments