NGA Turns The Clock Forward on Innovation

Geospatial intelligence technology rapidly is advancing and in some ways leaving behind the U.S. Defense Department and intelligence community. Looking to stay on the cutting edge, the nation’s premier geospatial intelligence agency is reorganizing its research and development arm to focus more on long-term research and developing closer ties to other agencies, the private sector and academia.

In July, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) officially cut the ribbon on NGA Research, which intends to take more of a strategic approach to research than the organization it replaces: InnoVision, which was largely centered on shorter-term applied development. NGA Research focuses on seven essential topics or pods, including automation, anticipatory analytics, geophysics, geospatial cyber, radar, spectral and environment and culture.

Among other benefits, the switch reduces redundancy. “There’s organization change and also change in foci and change in operation going from the old NGA InnoVision to NGA Research,” says Peter Highnam, the NGA’s new research director. “There was a perception certainly that they were doing more in terms of applied development working with nearer-term projects than you would expect a research and development organization to do. There are a number of organizations around NGA that do advanced development.”

But the change is designed primarily to keep the NGA at the forefront of geospatial intelligence technology. “The environment in which we all exist in the intelligence community and the Defense Department has been changing rapidly, especially in the areas related to geospatial intelligence, or GEOINT,” Highnam observes. “Our job is to get science under control.”

He compares the NGA to a stick on a stream or a river. The water represents the commercial and academic worlds. “If you’re that stick, you’re a technical organization without a functioning research organization. You can go no faster than the stream around you and frequently a little bit slower. You end up being a follower,” Highnam says. “That was the urgency of stepping up the longer-range strategic research and development within NGA.”

He intends for NGA Research to cultivate closer ties to the two organizations he refers to collectively as the ARPAs, meaning the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), as well as other research and development laboratories, such as the Office of Naval Research. “We’re moving away from trying to invent things in-house, which leads you back toward advanced development. We’re saying DARPA’s there with $2.8 billion or $2.9 billion a year of research and development money, working on behalf of national security. IARPA’s there too, directly working advanced research for the intelligence community,” Highnam notes. “We know what they’re doing and where they’re pushing the state of the art.”

The reorganization in part is intended to ensure that research serves a purpose. Highnam says the agency will be “taking ownership of transitioning technology and science results into practice, not just tossing it over the transom.”

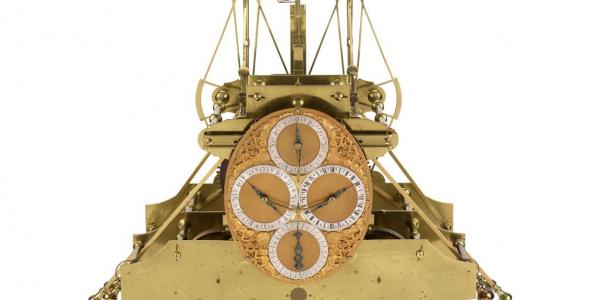

He cites the historical example of the “Harrison clock” to illustrate the newfound purpose for NGA Research. John Harrison, a clockmaker, invented the marine chronometer in response to a British naval disaster in 1707. The British government held a competition to find a solution for calculating longitude. Most experts thought an astronomy-based device would be the answer, but Harrison’s timing device proved superior. And, of course, today’s Global Positioning System (GPS) still uses time-based navigation, Highnam points out.

“It was a clock, something made completely independently of the stars, that was used to make navigation possible. So, a national security disaster drove a full and open competition that was won by a technology from left field,” Highnam adds. “That’s what we do.”

He continues that NGA Research has key differences from other research and development organizations. The ARPAs, for example, bring in new program managers every few years, while the NGA employs a more permanent staff. He sees value, however, in having his staff spend time in those temporary positions at the other agencies. “There’s a natural partnership there. If we can get folks over to the ARPAs to do those limited tours, they see a much broader technology base and customer base than just NGA, and ... they’ll come back and help to make NGA better for it,” Highnam says.

He praises another major change designed to keep the agency on the front end of innovation: the eNGAge program. The effort allows NGA employees to spend time within industry or academia and vice versa. Highnam counts himself an honorary participant in the eNGAge program because he was brought in by “limited-term hiring authority” from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. “I’m a big believer in what that program can bring to us in terms of bringing talent or expertise in for a limited term to help us bootstrap an area quickly,” he states. “What I am most intrigued by is having our people do tours the other way.” No one has come forward to do that yet, he adds, but he is open to the idea.

The eNGAge program essentially consolidates all the existing efforts that allow employee exchanges. Those efforts have been neither well-promoted nor well-used, report Michael Geggus, NGA’s industry innovation advocate, and Elizabeth Hoag, eNGAge program manager. “What we were noticing was that we have a number of vehicles that allow us to have these [personnel] exchanges, but there wasn’t a lot of awareness of them or of how they could be utilized,” Hoag says. “ENGAge takes the vehicles that allow us to send people out and to bring people in and centers them all in one place.”

In previous years, Geggus says, employees may have wanted to participate in an exchange but found the process too cumbersome and confusing. “We’ve always left our key components or offices or portfolio managers on their own. Sometimes the process of navigating your way through intergovernmental personnel action and contracting and agreements is a tremendous amount of work, and it takes heroic acts to make that happen,” he asserts. “I like to say it’s going from heroics to habits.”

Geggus explains that as the agency’s industry advocate, he has two goals: to create a stronger government-industry relationship that feeds innovation and to help government “recognize and understand that industry is quickly outpacing us in innovation as part of the rapid, global changes going on” in information technology.

“The thinking that’s happening within the government really hasn’t kept up to pace with that. We recognize that we need to get some of our folks exposed out into industry, create this collective learning experience where we can in a more rapid way get that understanding of how some in industry are reinventing our business or scaling it or extending it in some ways that aren’t from our traditional point of view,” he says.

Private industry, for example, has moved beyond the traditional mapping process. “One of the ways we’ve always created maps was using satellite imagery and control points and a multitude of other more laborious activities,” Geggus points out, cautioning that he is no technical expert on the matter. “Today, maps are being made by hired mappers using drone data from amateur and professional drone operators. Mapbox is using cellphones to create high-precision maps.”

Ideally, the eNGAge program will allow the NGA to develop partnerships with both traditional and nontraditional businesses. “When we talk about traditional and nontraditional partners, we’re really talking about what’s typically known as the military-industrial base in this area and the Silicon Valley new startups,” Geggus explains, noting that the nontraditional companies are outpacing traditional ones.

Hoag adds that the eNGAge program allows the agency to create more partnership opportunities. “It’s allowing us to move beyond the one-off, happen-to-know-an-individual relationship that develops one individual exchange. There may be businesses out there that aren’t geospatial intelligence right now, but the method, model or technology can easily be converted to something that we need,” she offers.

But technology is not the only area of innovation drawing the NGA’s attention. Officials say it also includes business processes and operations. Highnam suggests that might be eliminating a particular spreadsheet or work process to save time and money. Geggus touts lessons learned from “the lean startup movement,” which offers methodologies new to the government arena.

The agency is moving forward with other innovation-oriented activities, including the creation of a Silicon Valley office known as the NGA Outpost Valley. The NGA also has established the In-Q-Tel Interface Center, which partners with In-Q-Tel to identify, adapt and deliver innovative technology solutions from the commercial sector, especially small startups. In addition, the GEOINT Pathfinder 2 project provides unclassified geospatial data through mobile devices to support intelligence operations.

Lastly, officials have announced a joint effort with the National Reconnaissance Office to better leverage emerging commercial geospatial intelligence. The Commercial GEOINT Activity “allows both agencies to assess current capabilities and develop strategies to ensure the timely and successful integration of commercial innovations,” according to a written announcement.

Both the eNGAge program and NGA Research were announced earlier this year. Although NGA Research is fully up and running, it will take time before it truly acts as a new organization rather than one in transition, Highnam says. Geggus and Hoag, meanwhile, report that the response to the eNGAge announcement so far has been strong.

The agency published a list of areas of interest for the eNGAge program. It includes enterprise cloud solutions, computer-based modeling and simulation, business analytics and 3-D surface generation and editing. But Hoag says entrepreneurs should not feel limited by the list. “If you have an idea, call us. Don’t just sit on your idea because we didn’t specifically ask for it,” she urges.

Comment

Add new comment | SIGNAL Magazine

Stunning story there. What occurred after? Thanks!

Comments