Preventative Health Care: AI Aids Accessibility

In the United States, AI shows promise in assisting underserved communities by supporting preventative health care.

While the commercialization of AI has grown immensely in recent years, the health care industry must act differently, and for good reason. “In health, we have to look at the ethics of applying technology, and we come from a mindset where whether it’s technology, whether it’s vaccines, it should be safe and efficacious before you launch it,” shared Belinda Seto, deputy director at the Office of Data Science Strategy for the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

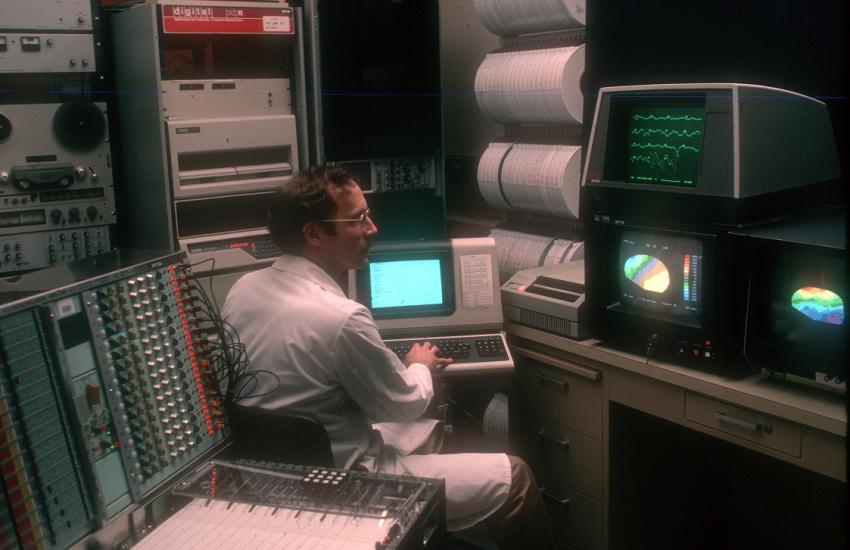

“Artificial intelligence has been used in health more prominently in medical radiology,” she stated. As a tool, machine learning has been helpful in analyzing images to gain comprehensive insight into pattern recognition. “By default, it will also inform us when there is an abnormal pattern to what the images are showing us, and therefore, it improves the detection and the diagnosis of a disease.”

For Seto, understanding and deciphering patterns has been a longtime passion. Having moved to the United States in the fifth grade, Seto’s love for science began with her enticement for Hong Kong’s local tropical flowers. In fact, the patterns and irregularities within petals and blossoms fascinated her to the point of pursuing an undergraduate degree in biology.

In graduate school, Seto earned her Ph.D. in biochemistry from Purdue University. “I delved a lot deeper into mechanistically, what are some of the processes that make our cells function? How do these individual biochemical processes come about?” she explained. “Basically, I studied protein chemistry and enzymes.”

Her journey later took her from the Stadtman Lab of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute to the Federal Drug Administration and back to the NIH. “Over the course of my career, I have taken multiple leadership positions, both in terms of policy leadership, program leadership and now in the office of data science,” Seto said. “I felt like I’m in the midst of this huge opportunity of crucible of things that are being experimented, things that one could see happening and implemented in real life situations, but wow, the whole time this technology is evolving!”

An evolving technological landscape requires a cultural shift, however. With a mission to improve the disparity in access and quality of care, Seto wishes to see further health equity in the nation. “There is not a linear path,” she went on.

“Let’s say you have the best diagnostic test. The deployment of that could very much be based on access to that technology. Secondly, there are structural barriers to access; there are cultural issues about acceptance of that technology,” Seto explained. The dissemination of health and science literacy is crucial, she stated.

The adoption of modern technologies such as AI depends on resources available for each respective clinic, hospital or institution. Additionally, it would require a change in workflow and a reengineering of operating procedures, including teaching and training that stays parallel to the constant updates of technological evolutions.

A similar approach is taken in health care data sharing. The NIH data-sharing policy, which has been in place since 2013, has evolved to require all researchers—no matter how much money they received from the NIH—to share data and management gathered.

“Data sharing was never and is not about technology ... it’s about culture,” Seto stated. The idea of generating data spanning many years of research, and only sharing it much later, is no longer acceptable, she explained. “It’s about common good; it’s about community good.”

Genomic and phenotypic data are treated especially carefully.

Before Francis Collins took the lead at the NIH, he was director of the National Human Genome Institute. “He was very keen and forward-looking,” Seto shared. Collins found that if certain individuals, based on their genomic data, are at risk of disease, they could be discriminated against in future job or housing opportunities. “You see, it’s about discrimination.”

Collins was influential in educating the U.S. Congress, which later led to President George W. Bush signing the U.S. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) into law on May 21, 2008.

As with any data, privacy presents concerns. And while the NIH believes in open access, measures and policies are still in place to protect the privacy and confidentiality of individuals.

“We ultimately really appreciate people who volunteer for clinical trials,” Seto stated. “We owe it to them to protect their privacy, so it’s ultimately about respect.”

At the NIH, data management and sharing practices must comply with findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable data principles.

For Seto, her hope is that modern technology like AI will improve preventative health promotion and access to care by lowering the structural barriers. It can also help the NIH disseminate the information gathered from research, Seto told SIGNAL Media.

Chatbots, for example, can be used to remind patients to receive regular and critical checkups.

“I think there are so many opportunities in the preventative arena to help improve health care in this nation, and we need to implement it at a community level,” Seto stated. Maternal and infant mortality rates, for example, are much too high and not what they should be in a First World economy.

AI’s help with health promotion messages can serve as a reminder for pregnant women to seek prenatal care.

A nation leading the way in health literacy and leading-edge technology implementation, however, is Singapore. “It’s a city-state that has invested in education and invested in their population’s health.”

Though the island country’s population is only a fraction of that of the United States, it can still serve as an example in the treatment of underserved communities.

“It’s a matter of priorities,” Seto concluded.

Comments