Retrofit or Start From Scratch? It's Not a Simple Choice

It seems like a simple choice. You need to upgrade a platform’s computing capabilities—whether on a ground vehicle, a fast-delivery ship, a signal’s intelligence airplane or in a server room—but some of the existing hardware still is salvageable. Rather than do a complete upgrade from scratch, it is possible to leverage much of the existing technology and retain existing racks, power supplies and mass storage in the retrofit. It makes perfect sense: Why throw away parts that seem to be working? But a closer inspection might reveal a different answer. Let’s peel back a few layers and see why—and when—it might make sense to throw away existing equipment and start over.

You never know what’s behind the walls

As with a home contractor, when vendors perform a retrofit, there’s always one line left open on the contract because they don’t know what they’re going to find. The contractor might find termites, faulty plumbing or other damage. In the high-performance computing industry, initial testing to determine the viability of existing equipment can be time-consuming and costly as the customer pays for design services and fixes.

Buying design or manufacturing rights might not pay off

Along those same lines, customers should be skeptical about buying a design or the manufacturing rights. Most vendors love it and almost always oblige. The reason is rarely do customers execute on it, and if they do, it costs much more than anticipated. Getting the manufacturing rights usually is just the beginning of problems because designers typically find they need much more information than initially projected.

Cost savings are rare with a retrofit, especially considering the total cost of ownership over a long period. Those adamant about a retrofit should do their best to get a fixed contract—even if they think it costs more. That way, the manufacturer is responsible for any surprises.

A real-world example: the Army’s WIN-T program

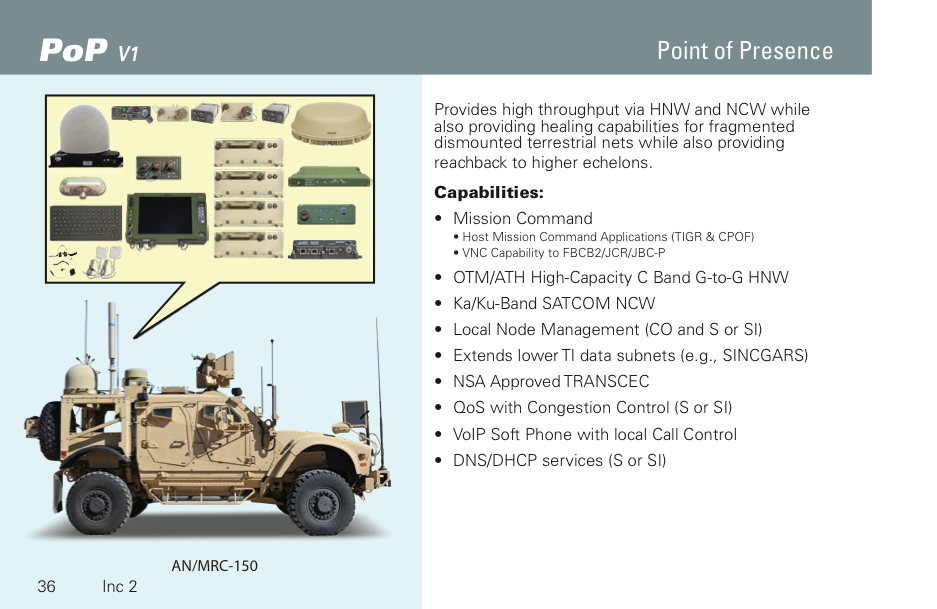

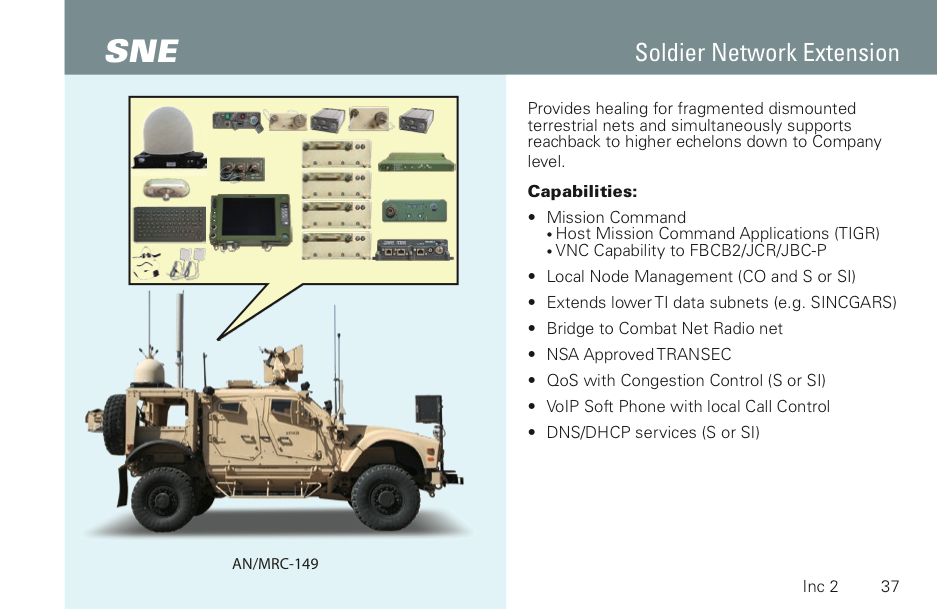

The Warfighter Information Network–Tactical (WIN-T) program initially deployed with an embedded computer based on Intel’s Core 2 Duo processor, which later was upgraded as the program’s performance needs evolved. Yet last year, we worked with the U.S. Army and General Dynamics to develop an entirely new embedded system that skipped two generations of embedded processors and converted to Intel’s latest Xeon D server class processors.

These offer up to 16 cores, or four times the number previously available, and add substantially more networking and communications features. Getting off the retrofit cycle let WIN-T significantly increase performance and lower system cost. In fact, in the Point of Presence and Soldier Network Extension components, one box now replaces up to five boxes in the local area network and wide area network. This kind of size, weight and power (SWaP) reduction took collaborative thinking and a whole new embedded computer architecture.

Since fewer components are needed in the new design for similar functionality, significant weight savings are possible. This is important for ground vehicle aircraft or other mobile platforms. In the WIN-T example, the new design reduced system weight by hundreds of pounds, freed up considerable space in the vehicles and reduced heat from those now-gone boxes—heat that often was radiated to the crew making for an uncomfortable environment.

Rule of thumb for redesign versus retrofit

If the equipment is more than three or four generations old—with a generation being defined as a new microprocessor and associated hardware—users are better off tossing it and redoing the design from scratch. Assuming a new generation arrives about every three years, a good estimate is about 10 years can pass before the contemplation between new design verses retrofit needs to take place. Technology is disposable, not something to be married to forever.

Ben Sharfi is CEO of General Micro Systems.

Comments