Siri, Uncle SAM Needs You

Researchers from the United States and the United Kingdom aim to identify inconsistencies between the data provided by intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance technologies and the understanding of that data by combat soldiers or other emergency personnel. The ultimate solution may be a Google- or Siri-type capability for intelligence.

The research is supported by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory (ARL) and the U.K. Ministry of Defence under the Network and Information Sciences International Technology Alliance, a 10-year agreement that lasts through 2016. The alliance brings together government, industry and academia to address the fundamental science underpinning the complex information network issues vital to future coalition military operations.

This particular project takes a unique approach to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance research (ISR), says Jonathan Bakdash, ARL research psychologist. “My collaborators in the United Kingdom are both computer scientists, but this work looks at it from a soldier perspective. Most research on ISR is really focused on it from a technical perspective, which is very important because sensors and systems have to perform technically, but ultimately it is the human, the soldier, who is using the technology,” Bakdash explains.

He emphasizes the importance of the soldier’s view. “Technology will continue to advance, and it is vital that we maintain a technological advantage, but maximizing the effectiveness of technology requires that soldiers are able to use it in an unpredictable environment,” Bakdash offers.

One of his collaborators in the United Kingdom agrees that other scientists largely have ignored the human part of the ISR equation. “I was surprised that so little work in the area of sensing technologies was looking at human factors. Lots of people were looking at middleware to make it easy to connect sensors to the network, or at information fusion from sensors, but few people were concerned with making those approaches easy for the end-user—the person who has the need for the data,” says Alun Preece, professor of intelligent systems, Cardiff University.

Preece goes on to explain the need for such research. “Advances in sensing and data processing technology mean that people in the field—including soldiers, emergency responders and police officers—have increasingly many ways to obtain information to assist their tasks. But they don’t necessarily have the expertise to know what sensors and sources can best assist them or how to go about accessing them,” he says.

Bakdash began his research in 2012. His approach featured interviewing soldiers about some of the challenges they face in working with ISR systems. Those challenges include platforms that are too noisy, continued problems sharing data with coalition partners or between echelons, and lack of a common operating picture. In many cases, soldiers will find creative solutions. “There are a variety of different issues that came up. And then [there are] some of the workarounds, like using unofficial ISR requests rather than going through the official planning process because it can be done in a more timely manner. It’s certainly not every soldier who does this, but it does happen, even infrequently,” Bakdash adds.

Soldiers sometimes will use a system’s weakness to their advantage. If an unmanned system is too noisy, for example, the soldiers will deliberately use it to announce their presence. “One of the more interesting things I heard is that some of the soldiers say, ‘Oh we just use that as the air version of a ground presence patrol. We use the fact that it is loud to draw attention to it, and that’s OK because we want people to know we’re there,’” Bakdash reports. “That’s a clever workaround on a technological limitation with some older platforms.”

The project now has reached a stage where collaborators are evaluating possible solutions. Bakdash emphasizes the research is very basic and long-term, looking 10 to 15 years into the future. “One solution is to think about the operational environment where the technology gets used. There’s a lot of unpredictability, and that includes the environment, the weather, the terrain, the time of day, the composition of the enemy, what the enemy is doing and the resources that are available to the Army,” Bakdash states. “One thing I’m working on right now is decision support systems, or systems that help inform what our capabilities are, and can help collect and sort through and fuse information.”

Automation may play a key role, but current techniques fall short. “How automation is typically conceived right now is the human supervises the system. One of my interests is making this more collaborative,” Bakdash says. That presents a major challenge because commercial systems are geared toward such things as tracking online clicks or purchases. When lives are at stake, however, humans must vet the information, limiting how much can be automated.

“In the military domain, it’s quite different. It’s safety critical and there has to be a rationale and justification for following a particular course of action,” Bakdash elaborates. “Soldiers are very cognizant of that. This is a critical consideration when building systems. It can’t just be, ‘The computer told me to do it.’”

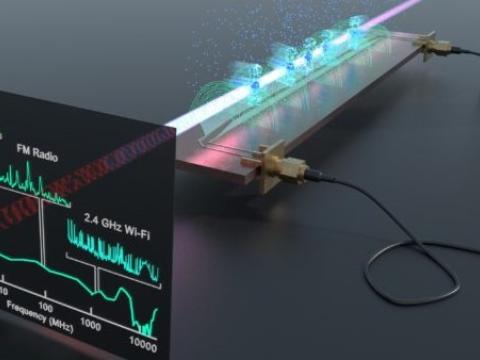

Ultimately, warfighters may end up with an intelligence system capable of carrying on a conversation either via text or voice communications. “One thing we’re talking about is looking at how conversational interfaces can be used to augment human decision making and intelligence collection,” Bakdash says, citing the Sensor Assignment to Missions (SAM) system developed at Cardiff by Preece and others. “It’s very much like Siri or Google now, but think of it in terms of intelligence functions.”

Preece describes SAM as a prototype software that allows users with limited training to state what kind of information they want and receive results. “Recently we’ve been experimenting with a conversational interface similar to Apple’s Siri we’ve developed to allow a user to ask SAM what they want,” Preece says. For example, a soldier could request information on vehicle movements in a remote valley. SAM can provide recommendations of available sensors, such as a drone, unattended camera systems or a network of seismic sensors, and then can be used to receive updates from one of those sensors. He adds that he would like to see SAM “in the hands of anyone who needs timely information from sensors to help them achieve their tasks in challenging field situations.

Bakdash says SAM and other prototypes look promising but still face hurdles, such as when people describe the same object or area in different terms that must all be represented by algorithms. One study conducted with graduate students showed they chose different words to describe a lobby area. Another study sought to determine whether a computer system could comprehend a human description of police officers on horses. Such problems can easily go undetected until the technology is placed in the hands of real users. “Humans are inherently unpredictable,” Bakdash offers.

With the cooperative agreement scheduled to end soon, it is possible the ARL and U.K. Ministry of Defence could sign a follow-on agreement. Whatever happens, Bakdash says, he hopes the research will continue. “No matter what, the sensors will get better. There will be much better data in the future. That’s pretty much a guarantee. And the challenges for soldiers will persist,” he declares.

Comments