Student Engineers Aid Injured Veterans

University engineering students across the country are plying their skills to address challenges for disabled veterans suffering from the loss of physical capabilities. Students apply mechanical solutions in a program called Quality of Life Plus to supply the missing link for a better quality of life after those who have served have been successfully treated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Even after Veterans Affairs (VA) provides prosthetic devices or other remedies, veterans may find subtle nuances that prevent them from being able to function effectively and enjoy life fully. Many of these problems are particular to individuals, although some of the solutions can be applied to others. Students in the program, which is also known as QL+, are paired with challenged veterans to develop a custom solution to whatever problem remains in their rehabilitation. The private, nonprofit program counts 13 colleges and universities as partners in its efforts to bring injured veterans along the last mile of their recovery.

Robert Wolff, executive director of QL+, relates that the organization was founded in 2008 by Jon Monett after he saw a documentary on the treatment and rehabilitation of injured service members. An engineering graduate of California Polytechnic State University—also known as Cal Poly—Monett arranged for the school to establish a program where engineering students assisted in developing adaptive technologies for injured veterans. Both Monett and Wolff are professional engineers and veterans. Monett served in the U.S. Air Force and the CIA for 26 years, and Wolff spent 26 years in the U.S. Army—nine years active duty and 17 as a reservist—along with five years as a civilian with the Air Force.

For many years, Cal Poly was the only school providing QL+ service. Then last year, the program added three more schools—the University of Dayton in Ohio, the Colorado School of Mines and Virginia Tech. Among the 13 partner institutions, many became aware of the program through individual relationships, Wolff explains, although some reached out to program officials through online postings.

Twelve of the 13 participants are engineering schools, Wolff relates. The exception is Xavier University in Cincinnati, which created a senior design course along with QL+ requirements. Among the engineering schools, mechanical engineering is the primary discipline being employed, although computer science and electrical and biomedical engineering students also play roles in these projects.

School protocols define the efforts, Wolff explains. As these are senior design projects, QL+ is simply a sponsor and an enabler. “We actually bring the project to the school; they have to accept the project, and then they create a team of students to work on the project,” Wolff says. “The actual process of designing a prototype, looking at options, constructing a prototype and working to a solution is all related to the school’s protocol.” This protocol might run either two semesters or three periods if a school parses its year into quarters, with each program concluding with the production of a prototype solution.

Wolff says the program describes its veterans as “challengers.” Eligible challengers are injured veterans—including those who were hurt after their military service—who have expressed a need, and most of them either have prosthetics or are wheelchair users. They tend to have received good care from the VA system, but they still want to extend their capabilities for everyday activities or even sports. Many need an engineering solution to help them participate in athletics, Wolff notes. “The veteran expresses a need that [he or she] feels that the students could work on a project to adapt to their need,” he says.

A veteran seeking a solution generally is selected through personal contacts, and the challenger is brought to the school to work with the students on the challenge. Most veterans are in the program for one year, although some have spent several years because of complicated challenges—usually those who are multiple amputees with various physical issues, Wolff says.

When a veteran contacts QL+, the organization asks for a short video expressing his or her need. Then someone from the organization writes a description of the need, and the QL+ director of operations, Col. Barbara Springer, USA (Ret.), selects the best school for the request. In some cases, the organization offers one project to a pair of schools or two projects to a single school, Wolff says. One aspect of school selection is whether the challenge requires a multidisciplinary approach, particularly in a mechanical versus scientific path, and whether that is suited to any specific schools.

Currently, most challengers are found through word of mouth, but the organization is looking to expand its reach. “The challenge will be to work with veterans organizations to tell them about our program and identify additional veterans,” Wolff declares. “We are doing OK this year, but for next year we do need to have a strategy to help us better identify veterans that can be in our program.”

The challenger pays nothing for the project or its solution. The program finances materials and supplies, and the students provide the labor, he explains. Student teams number between four and eight, and a faculty adviser oversees each team. A QL+ program manager is assigned to multiple projects at different schools.

Many of these schools discourage their engineering students from simply seizing the first solution to pop into their heads, Wolff notes. They want their students to explore different avenues in their search, which is more likely to generate innovative results.

Students working on these challenges are struck by the possibility that they will be helping to improve someone’s life immediately, Wolff offers. The organization tries to personalize the project by bringing together the two parties. In some cases, it has flown the veteran to the school—at the nonprofit’s expense—to meet the students at the project’s start. Videoconferencing plays a big role in the two-way communication between the challenger and the students throughout the project. And the organization covers costs when students bring their solution to the challenger’s home.

The lion’s share of challengers in the program are veterans who have served since 2001 in Southwest Asia, Wolff allows. Most Vietnam veterans are much older and less mobile, although two current projects aim to help those veterans. One project seeks a way for a retired wheelchair user to carry a suitcase, he offers, noting that a solution to this challenge could be generic.

Wolff continues that some solutions developed in the program could have far-reaching applications, and the organization is exploring how to extend that reach. He emphasizes that QL+ “is not in the business of commercializing these solutions.” The nonprofit has neither the means nor the money to commercialize technologies. Additionally, some schools maintain that their students own the intellectual property and receive any patents awarded for their developments. On the other hand, certain schools prohibit students from owning the intellectual property, and QL+ keeps it. The organization posts some of its solutions on its website, and it is looking at more active marketing of the products to increase awareness.

Wolff admits that the program doesn’t always solve a challenge, but the majority of its projects do. He cites several examples of innovations that aided veterans.

One challenger, a double amputee, had prosthetic legs that restored his original height. However, he wanted shorter legs to use for more flexibility when walking around his house. Students formed molds to create prosthetic legs they dubbed “shorties.” Today, that veteran looks much shorter, Wolff relates, but he is also much more comfortable walking around his house. An added benefit is that he can swim more easily, which he now does with his children.

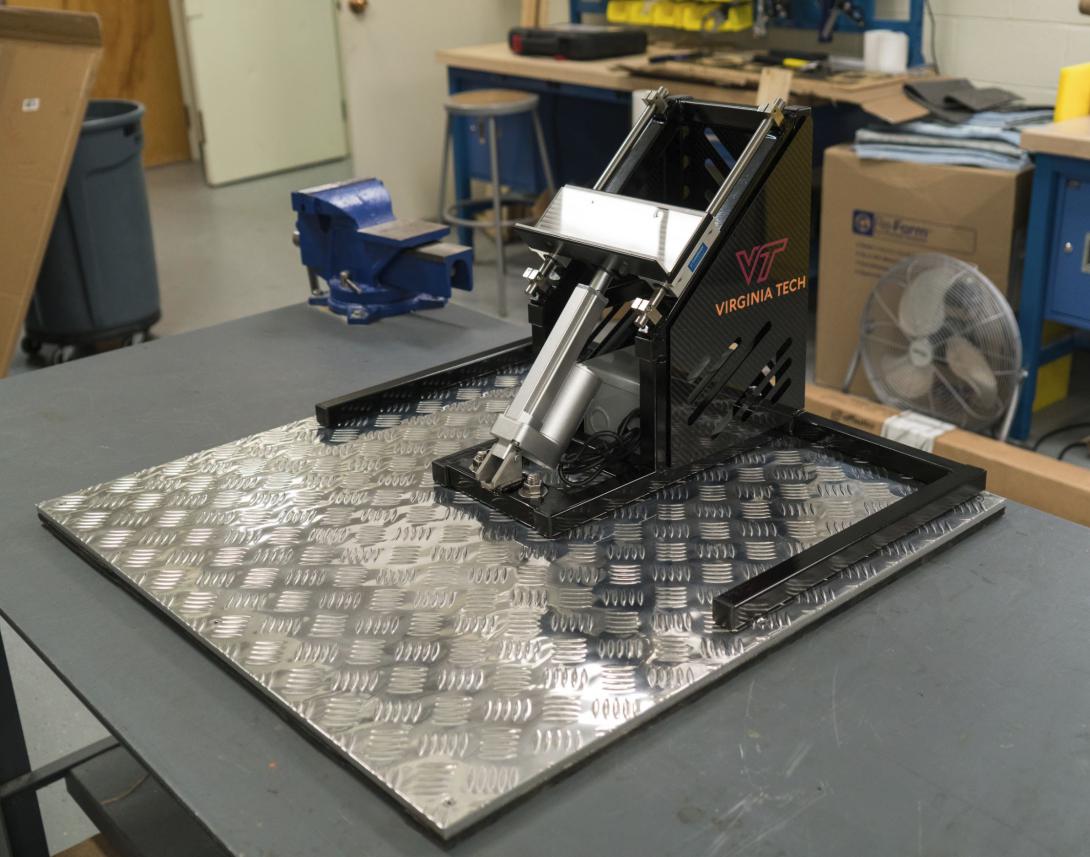

Another challenger living in Maine faced the problem of tracking in mud or other debris from her wheelchair when she entered the house amid dynamic New England weather. She wanted to be able to change the wheelchair wheels to a clean set at the door, much in the same manner her children doffed their shoes after entering. Virginia Tech students built a ramped device with a remote-controlled hydraulic lift that would elevate her wheelchair 3 inches. This allowed her to remove quick-release wheels and replace them with a clean set positioned near the door. After lowering the wheelchair, it would be ready for household use. The device allowed her to effectively remove the wheelchair’s “galoshes” upon entering her home.

An Army veteran who lost an arm and part of its shoulder to a rocket-propelled grenade in Iraq is an athlete who wanted to be able to perform push-ups. Students devised a spring-loaded apparatus on which she can place her damaged shoulder.

A recumbent bicycle used by one injured veteran posed a problem when he and his wife traveled. They struggled to lift it and attach it to the car’s rear bike rack. Students designed a hydraulic device that would lift the bike onto the rack, easing their burden. Wolff relates that the team of students traveled to the couple’s home to deliver the device, where it is now in use.

The program has served 25 veterans this year, compared with 34 total over previous years. The recent growth in the number of participating schools accounts for the substantial increase.

Wolff says future QL+ efforts will focus on finding more veterans rather than expanding the number of schools. The organization has signed a partnership agreement with the Society of American Military Engineers to spread the word through its 105 chapters in the United States and overseas. This provides a connection between veterans and engineers, which is right in the organization’s arena of operation. QL+ also is looking for mentors to advise the students, he says. And it is reaching out to nonmilitary challengers, such as first responders who have been injured in the line of duty.

One common denominator about these injured veterans that Wolff says impresses him is that “they haven’t stopped living.” They continue to find ways of making life worthwhile, he says, and this is inspiring. The QL+ program strives to help them in their quests to improve their lives.

Contact Quality of Life Plus and view a list of participating schools at https://qlplus.org.

Comments