From Pigeons to ESP

To say Leonard Rokaw has witnessed the communication revolution would be an understatement. When he first joined the Signal Corps in 1942, he relied on semaphore flags and homing pigeons to communicate.

The WWII veteran is incredibly well-spoken and has a lot to say about the changes he’s witnessed in his 97 and a half years of life.

Though he only served three years in uniform, he spent his career as a civilian working at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Home of the Signal Corps Laboratories and later the Signal Corps Center, Fort Monmouth has had its hand in every bit of communication technology we use today, says Rokaw.

Every piece of communication from radars, batteries, satellites and automation was pioneered or supported at the Army’s installation, he adds.

“I feel proud having been a part of some of the pioneering efforts and breakthroughs they made over the years,” beams Rokaw.

In 1928, the first radio-equipped meteorological balloon was released from Fort Monmouth into the atmosphere, a forerunner of a weather sounding technique universally used today. In 1938, the first U.S. aircraft detection radar was developed there.

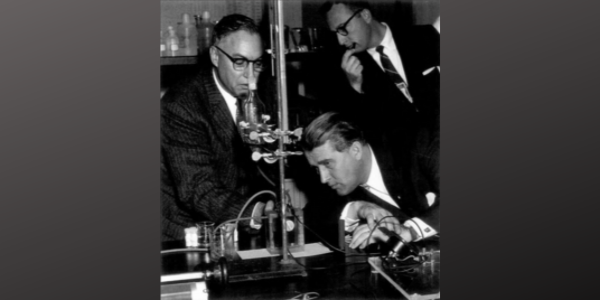

Rokaw played a role in Project Diana when he started at the Army’s post. In 1946, space communication proved feasible when the Signal Corps used the Diana Radar to bounce electronic signals off the moon. This opened the possibility of radio communications beyond the Earth for space probes and human explorers.

The Army’s homing pigeon service was also headquartered at Fort Monmouth. It was discontinued in 1957 due to advances in communication systems. Many courier pigeons were sold at auction, while “hero” pigeons with distinguished service records were donated to zoos.

Perhaps Rokaw’s most prized contribution was his work on Operation Paperclip between 1945 and 1959. The purpose of the secret program, in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers and technicians were sent to America for government employment, was U.S. military advantage in the Cold War and Space Race.

While working on this program, Rokaw crossed paths with Wernher von Braun, a pioneer of rocket technology and space science. Braun is credited with developing the rockets that launched the United States’ first space satellite, Explorer 1. He was also the chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle, the key instrument in getting man to the moon.

Rokaw was a charter member of AFCEA’s Fort Monmouth Chapter (now called Greater Monmouth) and was vital to its creation. Back in 1947, AFCEA was simply AFCA, the Armed Forces Communication Association. The name would change in 1954.

He recalls several interactions with Sparky Baird, former general manager of AFCEA and editor of SIGNAL Magazine. Col. W.J. Baird, USA (Ret.), became editor in 1956 and held the position for 18 years. He assumed the additional duty of AFCEA general manager in 1959.

“He [Baird] was the backbone of the organization, and it’s amazing it’s still alive and well today,” says Rokaw.

Rokaw rose to the top at Fort Monmouth and served as its director of public affairs from 1964 until his retirement in 1977. He oversaw the transition of six different commanders during that time.

He strongly believes communication supports the warfighter, not the other way around. “There’s no way they could function without it,” he states. “No matter what you look at today, batteries, radar, night vision … everything we do depends on communication electronics.”

Rokaw doesn’t think we’ve reached the end of the line yet in terms of communication. Though he admits the idea is still “kind of science fiction,” he wonders if some day we won’t depend on physical devices and will install some sort of extrasensory perception (ESP) in each soldier.

“We are still making improvements. You can see it happening in the devices everyone takes for granted. Hardly a person is walking around who doesn’t have a device in their hand or in their pocket that can do practically anything,” Rokaw says.

Comments