CIA Aims for Speed of Modernization for Infrastructure

New technology-based capabilities such as artificial intelligence/machine learning, automation, zero-trust security and satellite communications are on the menu for the Central Intelligence Agency as it modernizes its infrastructure with great alacrity.

The agency is facing the increasing challenge of more capable adversaries adopting widely available commercial technologies that change the threat rapidly. Meeting this challenge must be paired with a dynamic threat picture that is shifting the agency’s mission as it modernizes.

Effectively, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) must hit a moving target while also on the move itself. And the actions must take place at high speed. These infrastructure modernization changes must be incorporated over the next two to three years, says an agency official.

“The time frame is really now,” says Rodney L. Alto, former director of the Global Infrastructure Office within the Directorate of Digital Innovation at the CIA. Alto, who recently retired, made his comments in a SIGNAL interview while he was still director.

Alto notes that a crisis always is occurring somewhere on the globe, which constitutes a burden in balancing mission needs on infrastructure. In turn, infrastructure organization traditionally needs downtime to modernize.

One advantage Alto cites is that his organization includes many Type-A personalities who are at their best when confronted with “insurmountable infrastructure challenges,” and this capability becomes an incubator of innovation. “We really have exceptional government engineers, telecommunications professionals, program managers and software developers who, with our industry partners, deliver exceptional innovation globally in support of CIA missions every single day,” he declares.

Alto describes three key areas of modernization. Atop the list is automation, which he calls one of the agency’s most important investments. “In the infrastructure world, we need to automate everything we do,” he states. This includes functions such as zero-trust provisioning, operational support systems and business support systems. People must be removed from the middle of infrastructure change, he emphasizes.

“Automation is the foundational bedrock so that we can drive to higher-level services,” Alto says. It will enable greater use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in the agency’s information technology infrastructure.

The second area of modernization is information technology analytics. Over the past several years, the agency has focused on these analytics driving business decisions, Alto relates. He offers that this will continue to be a major growth area as the agency moves away from reactive processes to proactive technology engagement. It will require leveraging all information technology data for decision making, and this in turn mandates the use of AI to manage complex information technology ecosystems.

The third focus area is cyber. As the agency modernizes its infrastructure, cyber defense becomes paramount, particularly as older systems become more vulnerable to newer threats. Alto notes that some of the CIA’s older cyber systems actually lack vendor support, and the absence of even patches increases cyber threat vectors. Not only will modernizing CIA cyber provide new technology capabilities, but it also will eliminate many of these vulnerabilities while enhancing automation and telemetry.

For cybersecurity, zero trust looms, and Alto says it represents two major challenges. One is technology: industry partners are working to develop zero-trust solutions, but the transition to full zero-trust security in a government agency will take at least five to 10 years, he predicts. “This is a marathon; this is not a sprint,” he says. “Although there are a lot of people out there talking about rapid migration, it really is a marathon.”

The good news is that many technologies today already are embedded with aspects of zero trust that simply need to be activated to align with an organizational zero-trust architectural road map, he offers. Also, traditional industry networking, security and cloud companies already are offering mature zero-trust capabilities. Still, the transition at the CIA will be an involved process that must be aligned to the architectural road map, he emphasizes.

The second challenge for zero trust involves a familiar technology innovation challenge: culture. The concept of “trust nothing, validate everything all the time” that will dominate network security will present more challenges than the required technology changes that accompany zero trust, Alto offers.

The CIA, like many elements of government, has cloud service providers and cloud-first companies that are rapidly maturing zero-trust offerings, he adds. Still, a true, classified, multicloud, on-premise, zero-trust environment will be complex and needs to be orchestrated on a mature organizational architecture. This is particularly true of a hybrid- or multicloud environment. While the agency will continue to leverage industry zero-trust innovations, the agency must be able to adopt zero trust to an inside classified environment, which adds a layer of complexity with unique challenges, Alto says. He adds that he is confident that agency personnel with their analytic capability will be able to address them.

Cloud computing is only a part of the modernization that will be supported by industry. “Overall, commercial technology is the cornerstone of all that we do in enterprise information technology at the CIA,” Alto says. The agency is counting on commercial innovation to help it reach its technology goals, but it faces a challenge in innovation acquisition processes. These should be adapted to permit the agency to incorporate innovation at the speed of industry, he adds.

“As much as we talk about infrastructure modernization, acquisition modernization is equally important,” Alto warrants. “How we acquire services from our commercial industry partners … really needs a modern approach to transactions between government and industry.” Commercial business-to-business transactions have developed a process for rapid leveraging of new capabilities, he notes. “Stabilizing the budgetary investments in the infrastructure modernization, coupled with acquisition modernization, are going to be critically important over the next five to 10 years if we’re going to do this at the speed it needs to be done.”

The government budgetary cycle remains a big challenge. Alto states that CIA leadership is very supportive of the modernization effort, but the government five-year budgetary cycle often is disrupted by world events or rapidly evolving new priorities. The CIA’s new chief technology officer position and the chief information officer will play important roles in the infrastructure modernization, especially with regard to industry, Alto offers.

Another challenge entails having large information technology integrators leverage innovation from small businesses and startup firms, whether based in the United States or from elsewhere in the world. Many of these startups are the font of new capabilities the CIA needs, he notes.

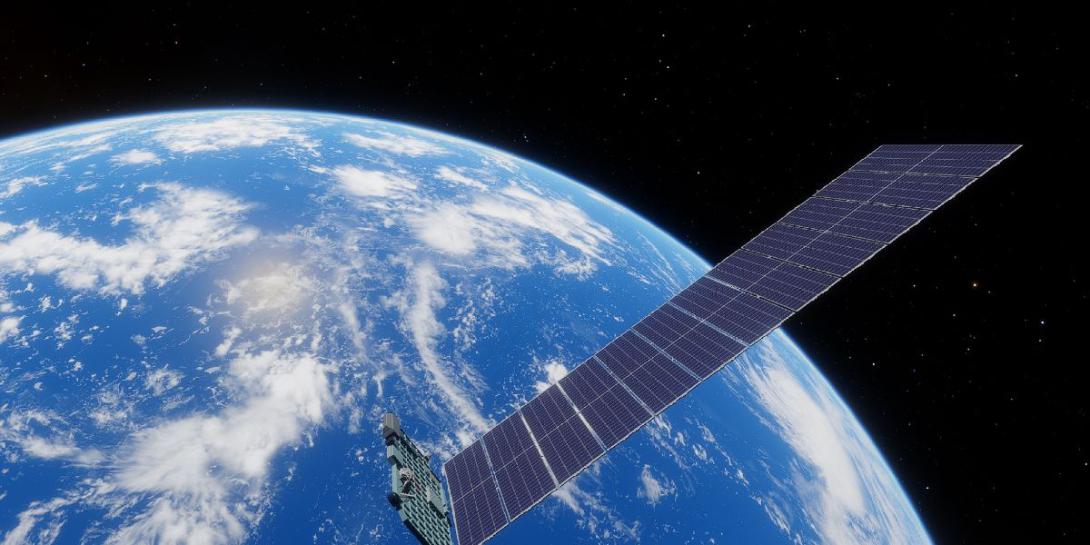

One such capability is defining the satellite industry. Alto notes that the development and deployment of new satellites and constellations in low, medium and geosynchronous Earth orbits (LEO, MEO and GEO) represents a generational disruption. These will redefine how government and society use satellite services globally, he states.

In LEO, Starlink is leading the way in delivering global satellite services with high capacity, low latency and low cost of entry compared to traditional satellite services, Alto continues. He offers that the biggest change will be in reduced costs of operation and maintenance and sustainment along with exponentially more capacity. “As we look at space, the future will be defined by continued rapid innovation and, quite frankly, the need for integration of LEO, MEO and GEO satellite services,” he predicts. The result will be robust global network capacity across the globe, and the CIA will look to leverage this generational change in satellite technology.

“This is a tipping point for the U.S. government as a whole,” he continues. “We will see great capability moved into space in a rapid period of time, unlike anything we’ve seen in the last 50 years.”

Satellite technology is part of an overall ecosystem to drive the breadth of cloud service capabilities to the edge worldwide. These new robust satellite services will give the agency greater resiliency in its network connectivity, Alto states, and it will have a data rate and speed not achievable over previous satellite constellations. He foresees ubiquitous connectivity by the 2025-26 timeframe.

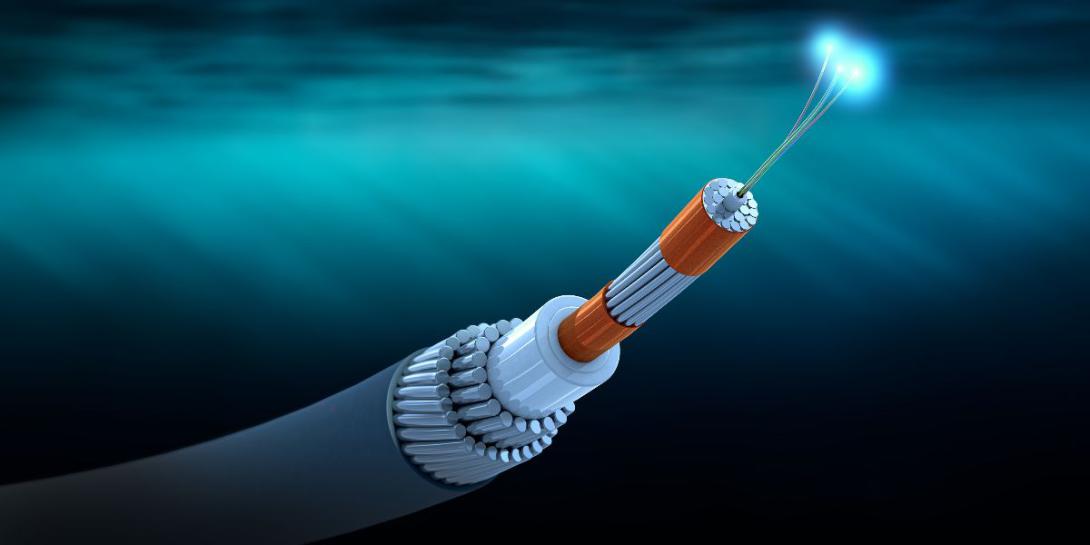

This connectivity will be backstopped by undersea cabling advances. Alto notes that the sheer capacity of the undersea cable network is essential for all government operations globally, but the industry must focus on resiliency to enhance reliability. Connectivity also must avoid persistent trouble spots such as the South China Sea, and resiliency must enable continued networking when natural disasters such as the recent Tonga volcanic eruption disrupt cabling. That eruption destroyed more than 50 miles of cabling connecting Tonga to the global Internet, Alto reports.

He notes that today’s global undersea cabling connectivity tends to be defined by point-to-point communication. Instead, planners need to rethink how to deliver the next generation of undersea cable infrastructure, which is likely to be defined as a more robust multipoint cable infrastructure. It will employ the latest technology along with greater resiliency. “It’s not a lack of capacity,” Alto allows, noting that new cables can carry more than 300 terabytes of data. “What we really need is global undersea resiliency.” It would be augmented by robust land-based terrestrial communications coupled with new satellite services, he adds.

This undersea infrastructure would be the purview of the commercial sector aided and abetted by large content and cloud providers such as Facebook, Microsoft, Google and Amazon, Alto notes. Those firms are driving the growth in undersea cable capacity to move their content worldwide. Government, on the other hand, while not the driver of that connectivity, stands to be the major beneficiary of that commercial sector investment.

Overall, most information technology modernization will come from industry. However, some niche capabilities will come from government engineers, Alto offers.

“The agency looks to fully leverage all technology to meet its mission needs,” he says. “Whatever that technology is, if it gives the CIA a decisive advantage in how we conduct our mission, the CIA will look to leverage and employ that capability, and quite often in partnership with industry where appropriate. If we think we have the capability and the capacity to do certain things ourselves that are unique, we will do that.”

For industry to provide the enhanced collaboration necessary for the CIA’s infrastructure modernization, it must have a deep functional understanding of the agency’s mission coupled with innovative contracts, Alto states. This is a two-way street, he emphasizes, as government managers must understand that continuous industry engagement is critical to the success of the modernization effort. This engagement must range from small startups to large government integrators, and it can’t be stymied by legacy processes, he says.

“The old model of putting out [requests for information] and waiting for things must evolve into a partnership and deep understanding by both industry and government that it is essential to our future,” Alto states. “That being the case, how we evolve our acquisition strategy to allow that innovation to happen will be critical.”

Among the capabilities the CIA will need for its infrastructure modernization are streamlined automation services across the entire infrastructure. This will serve as the key enabler for the agency to move into AI/ML capabilities. “The ability to collect and dissect the vast volumes of information technology telemetry that fully leverages AI and ML is going to be one of the inflection points where transformation of government technology becomes self-evident,” he points out. “People will see that we have much of the information in our information technology spaces today to make really better decisions, but the vast quantity of that really is going to require advanced AI and ML capabilities.”

This will help move the agency toward an environment comprising self-healing networks that offer the fast identification of anomalous behavior and a rapid response that is not necessarily predicated on large staff, he continues. Technology would be actively identifying and remediating those problems based on a historical and current analytic environment while applying AI capabilities.

He notes that commercial firms are putting AI and ML into nearly every new product, in many cases for anticipating human behavior. The methodologies spawned by those advances need to be employed in complex enterprises today, he states. Information technology telemetry has become too vast for people to grasp anymore, so AI and ML are needed as a predictive element for managing that information technology realm.

Comments