DARPA Program Aims to Help Counselors Spot Signs of Stress, PTSD

Every day, 22 veterans commit suicide—a startling number prompting experts to probe for methods to curb the national epidemic. Officials are fielding a new program, funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which can help experts assess the psychological state of troops and veterans early on and possibly get them the help needed before it’s too late.

The Detection and Computational Analysis of Psychological Signals (DCAPS) program joins the growing inventory of measures to combat depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicides. It has tools to analyze facial expressions, body gestures and speech, both content and delivery, and inform experts on a user’s psychological state of mind or alert them to behavioral changes that could indicate problems.

“We are now beginning to bring objective assessment to hard quantifiable data to make data-driven analysis, to come up with the indicators of distress,” explains Col. Daniel “Rags” Ragsdale, USA (Ret.), Ph.D., program manager with DARPA’s Information Innovation Office. “It’s almost like the period of time before the invention of the telescope. In astronomy, there were a lot of theories, many of them subjective, because they could not be based on hard, objective data. But with the introduction of the telescope—or in our case the introduction of systems that now can sense low-level psychological signals—we can now begin to build models that are based on hard, objective data that are going to complement the hundreds of years of expertise that’s been developed by subject matter experts as they performed largely subjective assessments to diagnose patients under distress.”

DCAPS can “facilitate the early identification, the early triage of these folks as they enter the military health care system,” Ragsdale says. “We felt like we could enhance, complement, reinforce, if you will, what [medical personnel] are doing in detecting psychological signals that would help us infer something about [a patient’s] cognitive, emotional state. The system is not meant to diagnose patients but to provide indicators of potential emotional distress.”

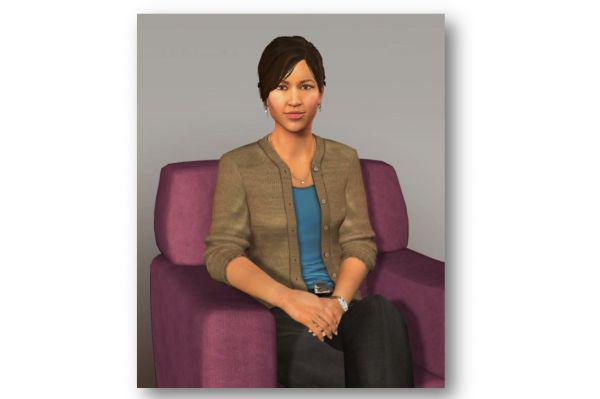

The program has several components, such as “Ellie” the avatar, a virtual human support agent to whom patients can talk. The program tracks eye movement, speech and body language. Experts learned that some PTSD sufferers “admitted they opened up more” when using Ellie, Ragsdale says. “All of us, to some degree or another, are reticent to share our shortcomings and failings and weaknesses to a ‘judging’ individual, but this is not a person. We know it’s not.

“There is no human in the loop here. They come into a setting, and they’re effectively talking to a screen, and there is a very lifelike avatar that is surprisingly realistic in its look,” he continues.

The program captures a patient’s a voice, plotting changes in speed or tone that might indicate stress. Through streaming video, the program tracks eye gaze and gestures. “All of these things are very important in trying to discern where a person is in a psychological or cognitive state.”

Another DCAPS feature is a smartphone app that tracks users’ daily habits and develops new algorithms to detect distress cues. Users opt in to have data analyzed. Experts look at data such as text and voice communications, sleep patterns, eating habits, social interactions and online behaviors to look for clue of stress, withdrawals or depression.

Users too are encouraged to keep a daily audio journal using the app. “Looking back on the day, there is a therapeutic effect that has been reported to us. In just unpacking your day and saying it, even to your smartphone, making a record of it, so even if you never go back and look at it, or a clinician never goes back and looks at it, that in and of itself, has value.”

According to report published by Cogito Corporation, a company that has smartphone-based behavior sensing systems, it surveyed DCAPS users over a 12-week period and analyzed input to 30,731 optional weekly survey questions and 1,217 participant audio check-ins, and conducted initial and follow-up clinical interviews. The research netted 51 million data points of bio-behavioral markers through mobile data collection. Among the results, researchers concluded the mobile app users are more likely than not to use the program, have low privacy concerns, and veterans are in favor of sharing the data with mental health and health professionals.

“I think it’s interesting to highlight that,” Ragsdale says. “We see the greatest benefit if they opt in, and the demographic that we’re targeting is more inclined to opt in than other demographics. This could be very useful for our high-risk populations if they seem to be going south, but for whatever reason, they’re not seeking care. This could allow them to get that care.”

The program also uses a baseball cap with wireless, noninvasive electroencephalogram to collect voltage readings from a patient’s skull surface and provide information on the possible emotional or cognitive state of an individual.

And DARPA and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) recently signed a memorandum of agreement, letting the VA launch a pilot study on the technology to assess whether it is suitable, either for patient care or as a training aide for VA counselors who can use it to assess their performance and interaction with patients.

Comments