Enemy Above the Gates

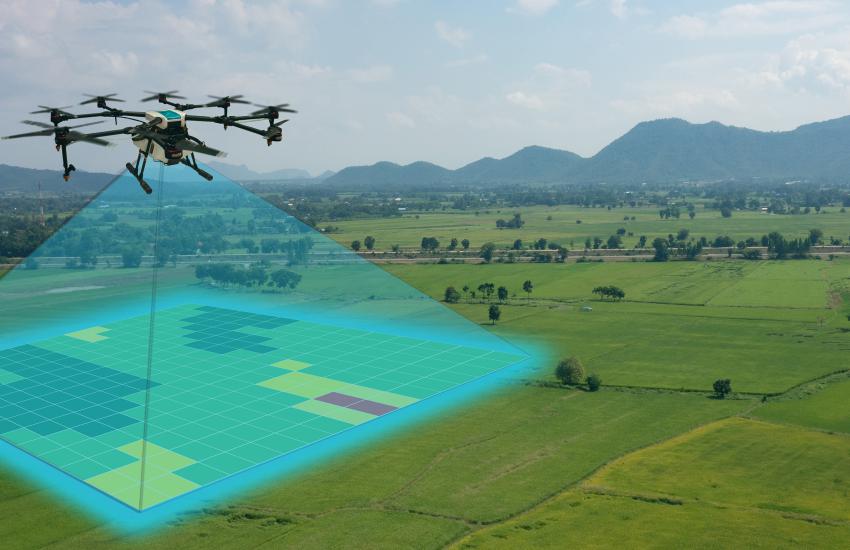

Anyone can fly a low-altitude commercial drone, albeit with some limitations. Nevertheless, currently, there are few restrictions on these flights as a lack of regulations makes them almost impossible to enforce.

“Given the rapid technology advancement and proliferation of unmanned aircraft systems, the public safety and homeland security communities addresses that drones can be used nefariously or maliciously to hurt people, disrupt activities and damage infrastructure,” said Shawn McDonald, Science and Technology program manager at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems office.

Events in the recent past have shown how significant the threats may be to the air travel industry.

In January 2019, Newark airport in New Jersey was closed for 90 minutes as a drone was illegally operating in the area. The cost of this disruption amounted to $90 million. In South Carolina, in 2018, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) caused a helicopter crash, making this the first accident of its kind ever recorded, according to a report by Athens University of Economics and Business.

An industry group identified drone intrusion in the vicinity of airports as a growing concern. “The penetration by an unauthorized aircraft into a portion of controlled airspace without prior permission from the air traffic services provider may result in multiple safety, efficiency, environmental and security risk concerns,” the International Civil Aviation Organization said in a working paper.

But for the DHS, risks go beyond airports.

“[Customs and Border Patrol] agents find drones that may have been used to smuggle drugs or people across the southern border. These drones usually carry narcotics and surveillance cameras, but they could carry other threats or hazards,” said Saadat Laiq, DHS Science and Technology program manager, in an email to SIGNAL Magazine.

In many cases, despite flagrant violations, little can be done.

“Current statute makes it illegal for state and local law enforcement to intercept communications or access a computer without authorization,” Rep. Peter Meijer (R-MI) said at a hearing in March 2022. “The existing restrictions on local law enforcement make it nearly impossible to track down the operator of a drone.”

A drone uses technologies, like remote controls, that, according to federal law, are considered private communications, therefore, can only be tapped following judicial procedure. Given the fluid nature of drone use, it’s impossible in practice to complete formalities on time.

Whereas border areas or airports could have several legal arguments to protect their airspaces from prying eyes, critical facilities may have fewer safeguards, and activity detected by law enforcement agencies is less clear.

Repeated flights over refineries, power plants or other infrastructure facilities around the country are regularly detected. Nevertheless, those who operate locations of critical interest can restrict unmanned flights, according to the widely cited section 2209 (49 USC 40101), which states applicants can petition the Federal Aviation Administration to effectively prohibit or restrict drones above or close to fixed facilities. And more regulation is expected.

The White House released The Domestic Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Systems National Action Plan in April 2022. This document lays out many of the benefits and potential risks in the field and outlines policy recommendations to be enacted by Congress.

“It assigns drone airspace, monitoring responsibility to local, state, municipal entities, which is appropriate, I think, because those are the organizations and entities responsible for monitoring events, for monitoring landmarks,” said Jon Schmid, political scientist at the RAND Corporation, a think tank.

As states and counties meet demands around these issues, some businesses are proposing technology to help mitigate the problem.

Money Flies

“We offer air defense that detects, tracks and classifies drones and the people flying them,” said Linda Ziemba, founder and CEO at AeroDefense, in an interview.

AeroDefense complies with the privacy limits set by law while giving those in critical sites the ability to follow activities.

The technology can spot a signal and pinpoint its location despite its crowded electromagnetic spectrum and resulting cacophony.

“The transmitters and other systems emit signals physically. This is similar to drug detection, and we’ve got very sophisticated algorithms that say, ‘Oh! there’s a drone,’” Ziemba said. Her business supplies fixed and mobile equipment to pinpoint the location of the drone operator. Of course, the equipment can’t know the intentions of the individual.

“We can identify that there is a drone and there is a pilot. We can’t tell you who it is until the law is changed,” Ziemba explained. Most users aren’t registered; their details are unknown to authorities.

While different product configurations may affect prices, a basic mobile monitoring station would cost $150,000 to $200,000 to set up and a $45,000 to $50,000 yearly payment, Ziemba offered.

Elevated to a national level, these budgets could be running too high too soon.

“We have to keep in mind how does the existence and the availability and the price point of a drone change that cost-benefit calculus,” said Katharina Best, associate director and drone researcher at the RAND Corporation.

While legal restrictions make enforcement difficult, these frameworks may be outdated by the time the legislative process is completed: the industry will develop new products and adversarial actors may use them with nefarious intentions, in a cycle teaming the human mind with constantly cheaper capabilities.

While it seems like authorities are fighting with one hand tied behind their backs, other aspects must be considered.

From a technological point of view, computer science can jump and leap, but physics is an inevitable science.

“If someone is doing something truly nefarious, they’re going to change [GPS] information, they’re going to set their location to be far away from where they [actually] are, and they’re going to spoof their GPS coordinates,” Ziemba explained. “So even if the law changed, and we were extracting [GPS] information, we would never stop what we’re doing because when you see the physical signal, you know it’s there.”

Depending on the location of the operator, whether they are on the move or not, a part of the detection process relies on physics and technology.

The DHS is also developing abilities for keeping airports safe and collaborating with U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials to prevent malign drones from becoming a physical threat to law enforcement officers.

“We are working collaboratively with Transportation Security Administration on their counter unmanned aircraft systems testbed in Miami International Airport. It will be used to test and evaluate best-of-breed drone detection, tracking and identification,” McDonald told SIGNAL Magazine in an email.

“Using the Safe Handling and Collection of Electronics—SHAKE—app, field personnel can determine a device’s make, model and unauthorized payload,” Laiq told SIGNAL Magazine. This mobile application can inform an agent if a UAV carries a payload or has been modified and to take due precaution before handling it.

According to Ziemba, as for the AeroDefense equipment, New Jersey State Police have deployed it in seven counties, including Jersey City. Also, it has been used at 50 federal correctional facilities around the country. AeroDefense, born in 2015, initially developed solutions for military use, but domestic operations also include a challenge in terms of what to do once the vehicle has been identified.

Signal jamming is among the many problems authorities face when neutralizing a drone. Signal jamming may disturb many activities, and some of these disturbances could be potentially hazardous to inhabitants’ health. This threat is part of the DHS testing in Miami. Interfering with the communications of an unauthorized device can’t pose risks to flight operations.

Kinetic solutions are also limited, as falling debris from a downed drone could harm people in the area.

The challenge of controlling UAVs is starting to be addressed as these machines evolve, and the future technological and legal frameworks should be flexible enough to allow law enforcement to keep up with the imagination of wrongdoers.

Comments