GeoMI Creates New 'Art' for Image Mosaicking with Software Solution

Imagery captured from UAVs can be up to 10 times less expensive than from manned aircraft or satellites, prompting government agencies and private farmers alike to investigate using the economical method. But piecing the puzzle hasn't always produced a workable solution.

Imagery captured from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can be up to 10 times less expensive than from manned aircraft or satellites, prompting government agencies and private farmers alike to investigate using the economical method to scan miles and miles, from power lines for infrastructure maintenance to railroads for servicing or acres of farmland for precision agriculture.

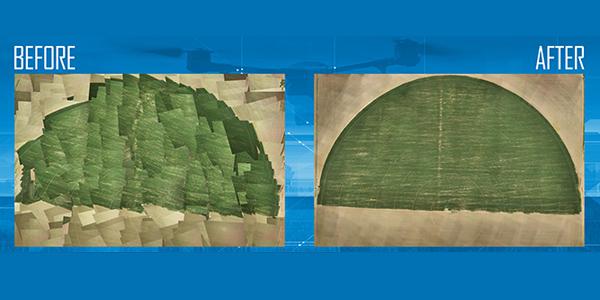

But compiling adjacent snapshots to form one large, usable image—a process called image mosaicking—has proven difficult as photo seams do not always properly line up, resulting in a skewed and faulty image. Using an algorithm that links images from low-flying UAVs, Lockheed Martin engineers devised a method to assemble numerous images to create a high-resolution mosaic—and shortened the time it takes to produce from days to hours.

“It’s a mathematical technique, and what it does is it first takes the images in pairs and registers them together,” explains Mark Pritt, systems engineer for Lockheed Martin. “When it does that, you have a set of what are called tie points that tie the two images together. But in order to do this for a large set of images, you also have to know what the coordinates of those points are on the ground. For example, you may have a feature in one image, say it’s a corner of a street, and it lines up with the same street corner in a second image. But you really need to know what the coordinates of that street corner are on the ground for this process to work.”

The bundle adjustment solution automatically makes an initial guess at the ground coordinates and on the position and the orientation of the camera for each of the images—accounting for variables such as wind and the position of the airborne UAV. “Using all of this information, it puts it into a massive set of equations and then seeks to minimize all of the contradictory information, or the errors, that’s within the system,” Pritt says.

The newly developed program could be ideal for processing images from satellites to UAVs and applicable to mapping forests, especially on a country-level, or surveying railroads, pipelines, farms and urban sprawl, and it can have military applications.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) restrictions prohibit small UAVs from flying higher than 400 feet, which can hamper the capturing of data over a large swath of land. For that, users had resorted to the image mosaicking process to create a large photograph for study.

“The value for this particular algorithm for the mosaicking really starts to become important as the volume of data increases,” explains Lee Hall, director of exploitation and visualization solutions at Lockheed Martin. “As the FAA opens the air space a little bit more for the use of UAVs, and you’re able to gather more data at a higher fidelity, the importance of being able to manage all of that data in a cost-effective way and process it at speeds, especially in tactical applications such as disaster response and the like, makes this type of algorithm application very attractive.”

Using conventional algorithms, when coupled with Lockheed Martin's automated georegistration software called GeoMI, thousands of images can be mosaicked, both more precisely and at a quicker pace, Pritt says. “We ran 5,000 images through the software, and it finished in 18 hours. That may sound like a long time, but we were very pleased with that. We could not process 5,000 images before—it was just too big of a problem for bundle adjustment to handle. When we run 1,000 images through, it takes about four hours to complete.”

Final product resolutions depend on the sensors and cameras taking the images. “What’s interesting about the small UAVs today, other than the fact that they’re very cheap, they fly very close to the ground and because of that, they get very good resolution. A lot of the imagery I’ve worked with has a resolution of 1 inch or better, meaning each pixel in the image corresponds to 1 square inch on the ground. That also makes it very suitable for farming applications when you need that kind of resolution in order to monitor your crop development.”

Comments