If You Build the Tools, Superconducting Electronics Will Come

Researchers for the U.S. intelligence community intend to build software applications that will make it easier to design and develop superconducting networks to power future supercomputers capable of much faster processing with lower energy requirements. The tools will reduce the time and cost to design superconductor-based circuits, potentially revolutionizing the computer and electronics industry.

Scientists across the planet are investigating superconducting materials that could transform electronics in much the same way silicon-based semiconductors did. Superconducting materials offer less resistance than semiconductors, so currents flow much faster. Niobium, for example, offers zero resistance at supercold, cryogenic temperatures, beginning somewhere around minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit.

Superconductors are touted as one of the great discoveries of quantum physics. They already are being used for the magnets in MRI machines and a few other applications. Superconductors may one day fuel superfast computers that will, of course, benefit intelligence agencies, which must process and analyze vast quantities of data. Superconducting technologies also may pave the way for superior electrical grids and even magnetic levitation trains.

However, semiconductors have a decades long head start and dominate the electronics industry. To advance the science of superconducting, researchers at the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) have begun to build electronic design automation and technology computer-aided design (TCAD) tools that will make it simpler to blueprint circuits based on superconducting materials.

“For a long time, people have talked about whether superconductors would be a viable alternative to semiconductors for advanced computing technologies. There are some potential advantages. They’re lower power. In principle, they’re faster. They’re radiation-hardened,” points out Mark Heiligman, who manages IARPA’s SuperTools program. “The semiconductor industry has been so remarkably successful over the past 60 years that any competitor has to catch up with this galloping behemoth, and it’s hard to do.”

The program’s short-term goal is to significantly reduce design time and increase the reliability of designs for complex circuits made of superconducting materials. The longer-term goal is to achieve a full, integrated design automation chain for digital-analog hybrid circuits. By making it faster and easier to design such circuits, IARPA researchers intend to spur the widespread adoption of superconductor technologies. Ultimately, the availability of design tools may foster “very large-scale integration design” of superconducting electronics, which can include “millions or even hundreds of millions of components on a single chip,” Heiligman offers.

While the intelligence community and others will benefit from faster computer-processing speeds, the rest of the nation could see a significant benefit from the reduced power consumption of electronics. Heiligman has coined the term “power budget” to describe all the electrical power generated for the country’s needs, whether from fossil fuels or nuclear, geothermal, hydroelectric or other sources. Much of that electricity—possibly as much as 15 percent, he suggests—is used for processing data.

“It’s hard to track exactly what the number is, but that’s a lot of power that we’re spending of our national electric production toward information processing. So, if you have a technology that will lead to lower-power computing with the same performance or perhaps better performance, that’s a very attractive thing to go after,” Heiligman asserts.

The program manager describes current computers as “power hogs,” adding that advances in processing speed are not as fast-paced as they once were. “You can build more of them and run more of them in parallel, but the actual raw speeds are not getting a whole lot faster, and that’s just due to the limitations in the underlying physics of the semiconductors,” he says.

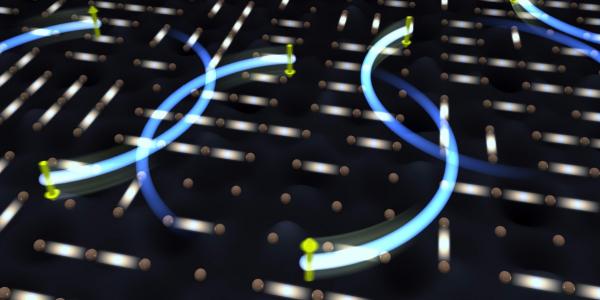

The lack of advances in conventional computers heightens awareness of the need for alternative technologies. However, designing circuits with superconducting materials such as niobium can be a tricky business. Achieving cryogenic temperatures is only part of the challenge. Traditional resistors behave differently in extreme cold, so superconducting circuits use Josephson junctions—which sandwich a thin layer of nonsuperconducting material between two layers of a superconductor—in their place.

In addition, with traditional computers, voltage levels determine whether digits are 1s and 0s, with 1s requiring more volts. But voltage is not a factor with superconductors. “There is no voltage. What you do have are little pulses of energy. The presence or absence of this pulse is a 1 or a 0. So now, all of your logical components produce your logical functions based on the presence or absence of these pulses,” Heiligman states.

Those researching superconducting materials often build the software tools they need for their specific scientific efforts without necessarily sharing the information with others. “If you build a complicated computer today, you don’t do it by hand. If it’s got millions of transistors in it ... you can’t wire them up to figure out how they’ll all work together. You can’t do it by hand. You have to do it by computer. Current computers design future computers,” Heiligman offers. “So, this whole program is really about trying to develop the software tools that will allow complex superconducting circuits to be built, designed, simulated and so forth. It’s about developing design tools.”

The SuperTools program focuses on four technology areas: logic design and synthesis; analog design; physical design and TCAD; and the SuperTools library. These are tools and terminologies used for conventional electronics that are being adapted for superconducting systems. The first three essentially help developers along each step of the circuit design process, including determining the intended function, implementing the functionality with digital logic and then turning that logic into actual electronic components.

“I don’t care whether it’s your cellphone or your thermostat or the electronics in your car. There’s a lot of complicated design that has to go on,” Heiligman observes.

He elaborates using made-up words he says are common among electrical engineers. “Engineers talk about ‘gozintas’ and ‘gozoutas.’ Think of a box. You’ve got a wire that goes into the box and a wire that goes outta the box. You’ve got a bunch of boxes, so the gozintas from one box go to the gozoutas of another box,” he jests.

The fourth focus area of the SuperTools program creates a library of software tools and solutions that can be reused to build similar circuits. “When you design something, you don’t build everything from scratch. You build on what you already know how to build. When we know how to build a particular kind of a logical component ... you solve that problem once and put the solution in a library,” Heiligman states.

SuperTools is a three-phase program, and he describes the phases as “big, bigger and even more bigger.” Researchers plan to design circuits, with 10,000 logical components in the first phase, 100,000 in the second and 1 million in the third. IARPA released a solicitation this summer, with proposals due in August. The SuperTools team will assess proposals through June 2017. Heiligman declined to estimate when a contract will be awarded, indicating that contract negotiations can take a long time, but he added, “We’re not going to drag our feet.”

Heiligman credits the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in part for the success of semiconductors. Historically, the same people researching the solid-state physics of electrical components such as transistors, capacitors, resistors and wires also were engaged in logic design, he recalls. In the 1970s and 1980s, however, DARPA began separating the two. “That split that occurred is one of the things that really enabled the semiconductor industry to take off. That allowed the people doing the logic design to build vastly more complicated circuits without being particularly worried about how they work at the underlying physics level,” Heiligman says.

Ideally, he says, the SuperTools program will do the same for superconductors. “If we succeed, we will have done a little bit to spur on a whole new technology industry,” he concludes.

Comments