The Internet Of Things Takes Shape

U.S. Defense Department researchers are meeting some goals ahead of schedule in their work on a program that may help make the Internet of Things a reality for the military and the rest of the world.

A fully functioning, futuristic Internet of Things (IoT) will require electronics that need not be plugged in or continually recharged, unlike today’s technologies. The IoT will need to be untethered. The Near Zero Power RF and Sensor Operations (N-ZERO) program, in which the RF stands for radio frequency, may do just that. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) effort seeks to overcome the power limitations of persistent sensing by allowing sensors to remain dormant—effectively asleep yet aware—until an event of interest awakens them.

The N-ZERO webpage explains that today’s state-of-the-art military sensors rely on active electronics to detect vibration, light, sound or other signals. That means they constantly consume power, primarily to process data, much of which turns out to be irrelevant. And even with state-of-the-art batteries, they last only a few weeks or months. The required power consumption has slowed the development of new sensor technologies and capabilities. Furthermore, the chronic need to redeploy sensors is costly, time-consuming and often dangerous for warfighters.

Through N-ZERO, researchers plan to dramatically improve the power efficiency of sensors at rest. Specifically, N-ZERO seeks to extend unattended sensor lifetime from weeks to years, cut maintenance costs and reduce the need for redeployments. Alternatively, N-ZERO also could reduce battery size for a typical ground-based sensor by a factor of 20 or more but preserve its operational lifetime.

Achieving the program’s goals could foster a true IoT, says Troy Olsson, DARPA’s N-ZERO program manager. “What we can do today really doesn’t fulfill the vision of the Internet of Things. We can either connect devices that have power already, like your refrigerator, or devices that you can recharge every day or every couple of days, like a cellular phone. You can connect and interconnect those, and some people call that the Internet of Things,” he offers. “When I think about the Internet of Things, I think about sensors everywhere that are untethered from either a power supply or from having to recharge the batteries all the time.”

The Defense Department has been researching and developing so-called persistent sensing technologies for years. Persistent sensing is used, for example, to protect troops at forward operating bases in combat theaters. “We would like, for a long time, to stick out a sensor network to detect incursions or dangerous chemicals or other things that might be present around our forward operating bases,” Olsson explains. “We can go out and change batteries every week or so, but that puts our soldiers in danger, and it requires a lot of manpower to support the maintenance of the sensor field.”

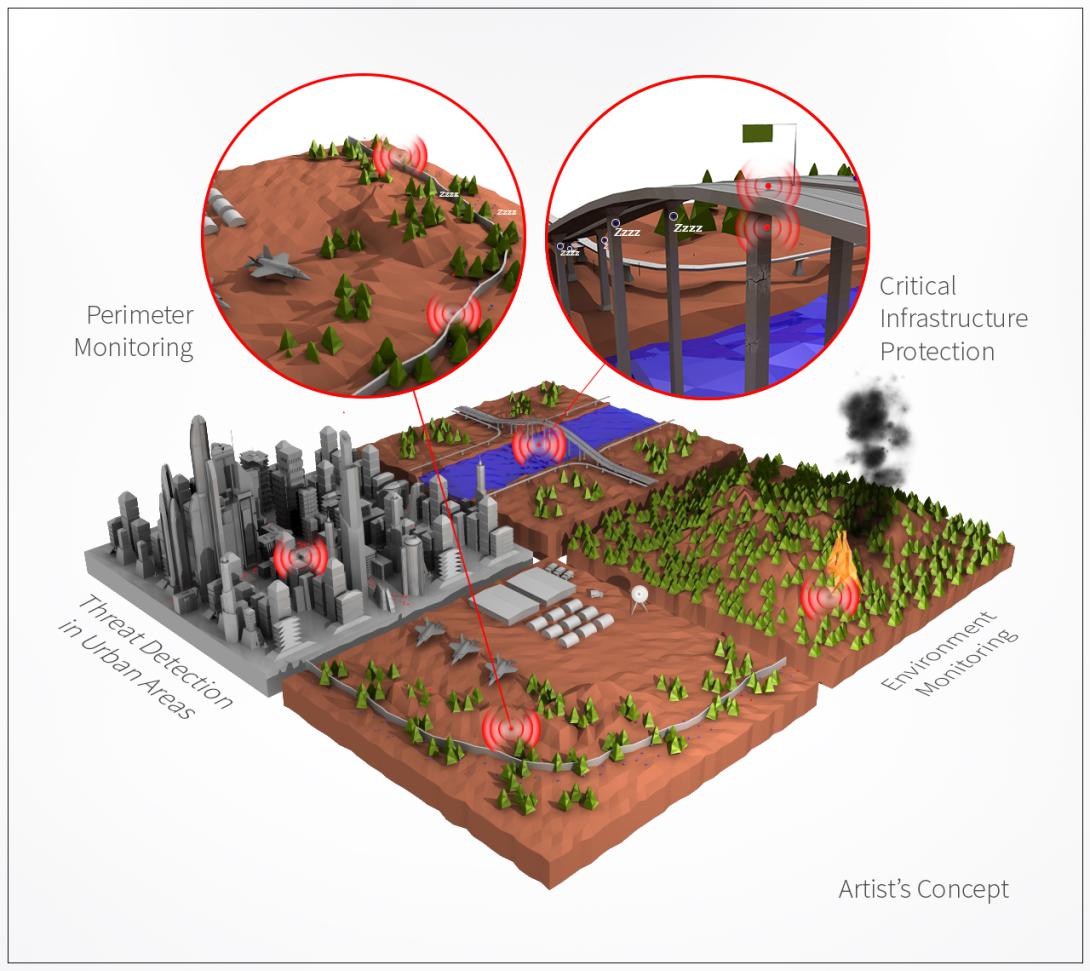

Meanwhile, the commercial world also is looking for a host of IoT sensors to perform a variety of roles, including detecting damage to critical infrastructure, such as bridges and buildings. Sensors are proliferating and already are found in mobile devices, automobiles, industrial control systems, medical devices and climate monitoring systems, to name a few.

However, Olsson cautions, N-ZERO technology will help only for infrequent events, such as forest fires, area intrusions, decaying infrastructure or worn machinery. “I want to be a little bit careful in qualifying how N-ZERO can help the Internet of Things. If you’re constantly sensing data and communicating it back to a network, N-ZERO is not going to help you because that communication, if it’s ongoing all the time, is going to suck down your battery life,” he says.

The program focuses on two broad areas: asleep-yet-aware sensors that awaken when needed and RF receiver technology that continuously seeks transmissions from those sensors yet consumes virtually no power when transmissions are not present. The sensors and the receiver both need to use less than 10 nanowatts during the asleep-yet-aware phase. Ten nanowatts are roughly equivalent to the amount of power discharged from a watch battery as it sits in storage, which is at least 1,000 times less than state-of-the-art sensors.

Because the battery will lose 10 nanowatts anyway, attempting to go below that threshold would offer diminishing returns. “We’re trying to enable sensor nodes that can operate for years off of cheap primary cell batteries. If the battery is going to self-discharge, consuming power that is well below that doesn’t add any value,” Olsson says.

The N-ZERO program is divided into three phases. The first, which wrapped up in December, took 15 months. Phases two and three will each take one year. Some research teams achieved goals in the program’s first phase that they were expected to reach much later.

For the receiver, the goals are to detect 60 decibel-milliwatt (dBm) RF signals in the first phase, -80 in phase two and -100 in phase three. “We’ve developed zero-power receivers that consume less than battery leakage—less than 10 nanowatts of power—that can sense RF signal power of lower than -70 decibel-milliwatts at real RF frequency, so in excess of 100 megahertz,” Olsson reports. Before the program started, he adds, the state of the art for receivers consuming less than 10 nanowatts was to detect signal power of only 35 dBm.

The receiver works by being tuned to a short, specialized code known as a preamble. Olsson compares it to the code division multiple access capability, which is essential to mobile phones because it allows users to share the same frequency without interference. “We’re looking for a coded preamble that has very low energy, so it doesn’t require the transmitter in the network to disadvantage itself,” he states.

An additional goal for the sensors in the first phase was to detect a generator less than 1 meter (3 feet) away in a rural background with an accuracy of 95 percent and only one false alarm per hour. Olsson explains why the false alarm rate is important. “We did some analysis of real systems, and we concluded that if we were waking them up unnecessarily once per hour and then putting them back to sleep, we could still get a couple of orders of magnitude gains in the lifetime of the overall system,” he states. “The other key piece is that you don’t want the total received energy to be very high because you don’t want to make the transmitter sit there and broadcast a low power for a long period of time and run out the transmitter’s battery.”

In the program’s current phase, those sensors need to distinguish between cars, trucks and generators in an urban environment at a close range. In the final phase, they will be required to classify those same targets from 10 meters (33 feet).

Some of the program’s competitors are exceeding expectations on that score. “The ability to sense and classify cars, trucks and generators in ... both rural and urban backgrounds from a distance of a little over 5 meters away and being able to do that with almost 10 nanowatts of power consumption is a big accomplishment in phase one of the program,” Olsson reveals.

Alternative solutions are possible. For example, the transmitter and receiver could be programmed to sleep most of the time and wake up at regular intervals. However, that approach easily could miss some events, such as enemy forces moving into sensitive territory. Furthermore, DARPA officials tout the asleep-yet-aware approach as the most efficient. “The least efficient thing you’re going to do in an unattended sensor is to transmit. You cannot transmit when nothing is awake to hear you. And the clocks it would take to synchronize two nodes so that they could sleep and wake up, sleep and wake up actually take more power than a traditional radio receiver,” Olsson elaborates. “As a result, receivers are left on all the time, and they are actually the dominant source of power draw in wireless sensor nodes.”

Olsson does not expect the N-ZERO program to result in a product ready for fielding. “I suspect what we’ll have are significant field demonstrations, but someone else will need to come in and productize what we’re doing and operationalize it either for the Department of Defense or the commercial IoT,” he says. “And I fully expect applications in both.”

Comment

IOT

I believe once the test phases are complete, the application for this are enormous both for DoD and commercially. You can set these sensors with UAVs and have them auto-launch for ISR/engagement. You can put them in houses and they can detect wear & tear hence tell the owner about needed repairs.If the sensors could also detect people approaching by body heat or movement it would greatly reduce patrols.

Connect US

Connect KMG Official Cabinet in US

Embassy in DRC.

Comments