Project Pushes Water Into Advancements for Biosensors

The latest results in graphene research show promise for improving electronics and biological or chemical sensors by pushing or pulling liquid droplets across the surface. By placing long chemical gradients onto the graphene, scientists can control the substances’ flow.

The latest advancement in graphene research shows promise for improving electronics and biological or chemical sensors by pushing or pulling liquid droplets across the surface. By placing long chemical gradients onto the graphene, scientists can control the substances’ flow. Through this capability, scientists can create larger puddles, making it easier to detect dangers such as nerve agents or bacteria in water.

Researchers at the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) performed the experiments testing the theory, and they published their work in the journal ACS Nano earlier this year. Scott Walton, one of the co-authors of the report, explains that building gradients onto other materials will enable many applications such as a combination of different graphene-based sensors. The graphene could integrate with other materials to enhance devices. Sandra Hernández, another co-author, says on a larger scale, the surface chemistry will enable bottom-up approaches to systems as well as development of hybrid or smart materials. These properties can advance substances for better use in electronics.

Graphene has interesting electronic, chemical and mechanical properties, and it can be transferred to arbitrary substrates. But because graphene is so thin—only an atom thick—it is delicate. The addition of the chemical gradient retains some of the properties, while also allowing the liquid droplets to move across the surface smoothly. The challenge is to create large area gradients without any “breaks” spots, which could cause the droplet to stop. These features facilitated the project’s success.

“The key is to have a gradient that increases in one direction (in the direction of motion) but remains largely uniform in the direction perpendicular to the direction of motion,” Walton explains. A basic analogy is a sliding board. It has to tilt down and be wide enough to accommodate riders.

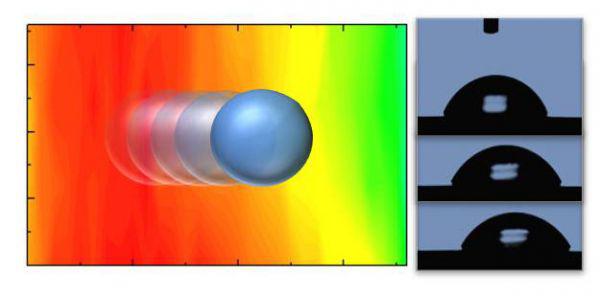

The project boils down to controlling surface interactions of materials of interest. Team members created two chemical gradients then tested water and dimethyl methylphosphonate on them. The later is a nerve-agent simulant. A gradient of oxygen functional groups pulled the liquids toward higher concentrations of oxygen while a fluorine gradient pushed the droplets toward decreasing concentrations of fluorine. The behaviors can lead to more sensitive sensors or ones that can distinguish among catalysts.

With the paper published, the scientists will look for additional funding to further research. But according to Paul Sheehan, a third co-author, the ideas are ready for more practical implementation. “We would love people to pick it up for application,” he explains. Biosensors could benefit from the concepts, with either the collection system or the sensor itself placed on the flexible substrates. The material also could gather nerve agents that land on its surface and send a catalyst that would degrade the danger. Military personnel could build that into uniforms to enhance troop safety.

The scientific community focuses large volumes of its research on graphene because of the unique advantages it offers. However, much of that centers on enhancing electronic properties. The NRL’s approach is different because it shows interesting physical effects. Authors compare what they did to the easily visible effect of water pooling on a leaf or petal in nature. The drops tend to slide toward the end. Similarly, scientists pushed the liquids to specific locations. In the future, they may manipulate smaller volumes or even single molecules.

Comments