Putting Innovation Into Practice

Companies or government agencies that strive for innovation have to keep development at the forefront, experts say. And the action of providing impactful ideas that turn into effective products is always “far more complicated in reality,” according to Jennifer Yates, assistant vice president, AT&T Labs.

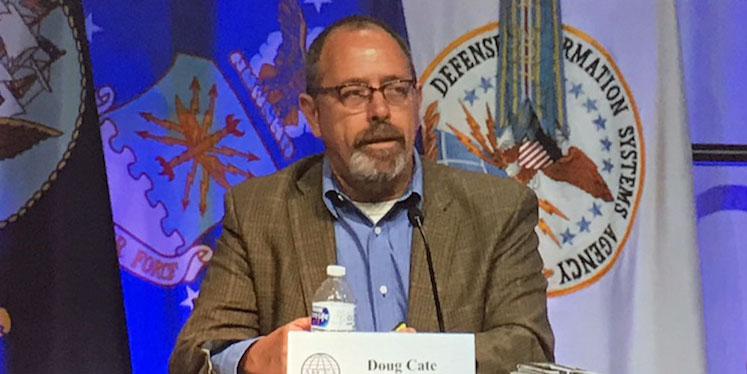

Yates and other seasoned innovators shared their experiences at the AFCEA Defensive Cyber Operations Symposium (DCOS) in Baltimore on May 15. Stephen Wallace, chief technology director, Development and Business Center, Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) moderated the panel of innovators, which also included Doug Cate, acting chief technology officer, Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA); Jeremy Corey, chief, Cyber Innovations and Assured Identity, DISA; Keith Johnson, chief technology officer and chief engineer, Leidos Defense and Intelligence Group; and Michael Chung, head of solutions, government, Bugcrowd.

Wallace stressed that the collaboration between industry and the government has been a key aspect of innovation throughout history. And while innovation may be more of a challenge in government, senior leaders providing “top cover” for more junior workers to develop emerging technologies is one key to innovation in the federal sector. Another aspect is consistent funding, he said, which the government does not always have.

Cate said the DIA uses a “Shark Tank”-like process in considering innovative ideas, looking at the desirability of the product, its viability, its strategic alignment with the department mission and whether or not there is leadership support. They first consider whether to invest in an “eight to 12-week sprint” to get a minimally viable product, then decide whether to fund more development. “We look at security and the design standards to get it to the next level,” he said. “[We consider] how do we drive out the uncertainty.” The DIA also makes sure to collect ideas through a “Shark Tank Pool,” and works to get lots of ideas “across the full spectrum view” of the agency.

In addition, Cate helped establish an innovation fund at DIA to put toward “year one” costs in developing technologies. After that, industry and government can help fund product development. “Fundamentally, we are not flexible,” he said. “Funding is built all around programs of record.” As it stands now, the procurement process is hindering innovation, he added. “We have to have acquisition reform.”

Yates suggested that innovation is more effective with input from customers. “We are always looking for clear impact and clear technical challenges,” she said, adding that some ideas may not appear to have a big business impact at first, and that ideas can easily come from the lower ranks. One recent idea came from an intern working in academia who was able to solve an important problem.

She also advised that companies or agencies partner closely with those who may be using the technology, then build a comfort level around the emerging product and roll it out with their support. "The key to innovation is building relationships and communication,” Yates said. The challenge, she admitted, is getting the right timing. She recommended having a pipeline of both short-range and riskier long-range ideas. “You have to believe that innovation will create the future.”

Meanwhile, Corey said that government innovators should “get out of the building” and go talk to industry, academia and laboratories. Then, when developing a prototype, it is important to reach across an agency when making a business use case. “It is essential to communicate with mission partners to help us understand how we could offer this service as an enterprise,” he said. He has also seen success in bringing in small startup groups who can quickly address capability gaps. The government needs to work on supporting a “fail fast, rapid prototyping” mentality. Corey also shared that innovation is not always about the technology. It corresponds to the existing problems and getting people to be part of the process.

Johnson agreed that implementing new ideas with a business impact is not always about technology and that small innovations could have big impacts. At Leidos, the company tries to encourage innovation within its teams. They have to carefully assess if they are really meeting the needs of the government, are staying on track and having regular communications with customers. “You have to encourage viscosity, and the flow of information, and reward staff for innovative ideas.

Johnson asked government officials to make sure that they are incorporating innovation into contracting by including it as a scorable criteria, which would drive companies to show how they would innovate as part of a project. Moreover, cybersecurity has to be included in innovation from the beginning. “In cyber, in particular it is about the people, and expertise can be applied in so many ways,” he said. “It’s not just adding a new box.”

Lastly, Chung shared that Bugcrowd, a small startup company, promoted empathy of its customers. “Innovation doesn’t really mean technology, but customer empathy. That, combined with agile methodologies, helps the company innovate. You have to define the business case for a potential product early on especially in software development,” he said. “Then if it is a successful impact, then expand.” He warned that cybersecurity may remain a capability gap, given a lack of experienced professionals, and that will continue to impact innovation, as well as homeland security. “We need to put our minds to the drawing board to address that,” Chung said.

Comments