Swarms and Strategy: Smaller Could Mean Smarter

In Ukraine’s ongoing conflict, low-cost drone swarms and AI advancements are reshaping military strategies, challenging traditional air power and highlighting the importance of affordable, adaptable technology in modern warfare.

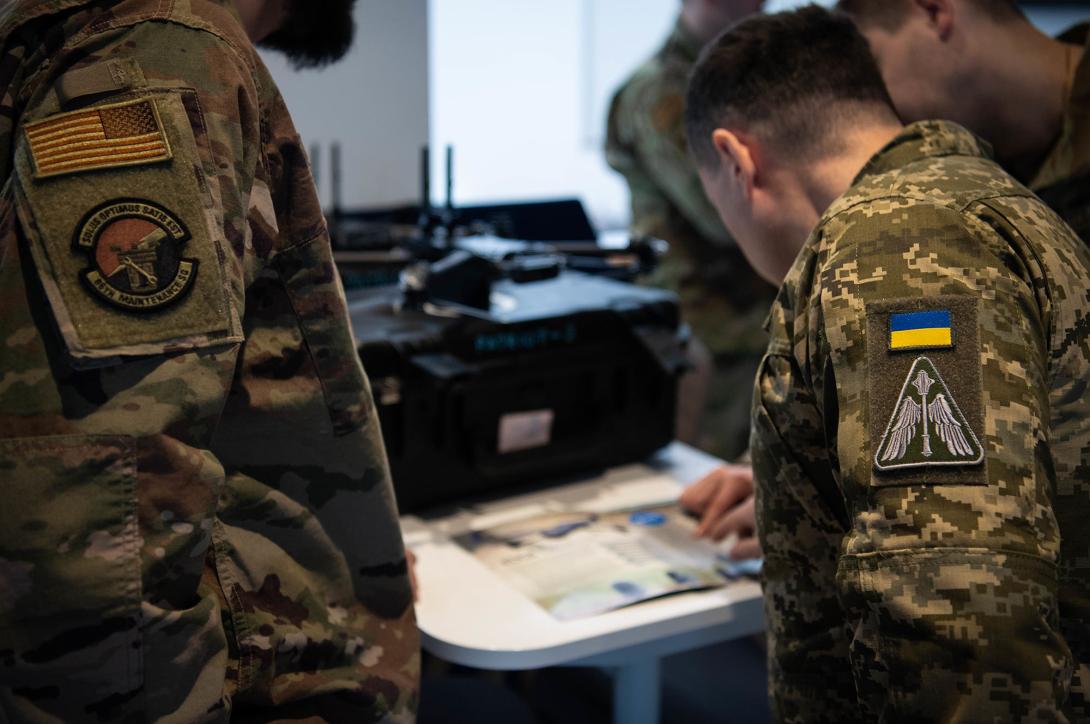

The development of low-cost, expendable, autonomous platforms emerged when a resource-constrained nation like Ukraine leveraged cheaper, smaller systems with high performance at the tactical edge. This adaptability in technology, combined with robust autonomy, can offset traditional military disadvantages, offering an outsized impact in asymmetric warfare contexts.

“This war of attrition that we’re seeing going on over there kind of defies common sense when you look at the amounts of money,” said Dan Javorsek, chief technology officer for EpiSci, a drone algorithm maker.

Low-cost drones have impacted the war in Eastern Europe, providing both sides with affordable, scalable options for surveillance, targeting and direct attacks. These inexpensive vehicles have disrupted traditional air power assumptions by democratizing access to aerial capabilities and challenging the dominance of expensive, high-tech aircraft. Their widespread use in Ukraine underscores the shift toward agile, expendable assets over large-scale, costly air fleets, prompting militaries to rethink air power strategies and defense budgets. This evolution reflects a new era where swarming, low-cost systems can effectively challenge traditional air superiority in modern warfare.

This market was valued at $13 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow to $18.2 billion in 2028, according to Markets and Markets, a research firm. Still, defining what is “small” or “expendable” depends on a series of conditions.

The focus on expendable vehicles hinges primarily on cost, often compared to traditional munitions like mortars or artillery shells.

The cost of a portable drone in Ukraine can go from $100 to $1,000. These are now replacing mortar rounds and serve as “smart mortars.”

“Now in Ukraine, for instance, in the backpack-size drone category, the FPV [first person view] size, like a 7- or 10-inch, these replace mortar rounds almost always,” explained Allan Evans, CEO of Unusual Machines, a drone manufacturer.

By contrast, In the United States, costs can be as high as $2,000, making such drones “expendable” compared to pricier fixed-wing models, which replace large artillery or missiles, according to Evans.

Nevertheless, success rates for these offensive FPV devices vary between 10% to 50% in Ukraine. Most are lost en route to their objectives, primarily through electronic means.

Technical advancements, like improving radio links to counter jamming and limited artificial intelligence (AI) enabling devices to function autonomously if the signal is lost, are paving the way forward. This “digital pilot” capability, allowing drones to self-direct toward targets, if necessary, could boost operational efficiency.

And size still matters.

“If you said what’s attritable for the big, fixed wings that carry much more explosives, you’re willing to pay more because you’re replacing missiles or big artillery shells,” Evans said.

Determining a drone’s expendability depends on the objective and cost-effectiveness, where using multiple low-cost drones is acceptable if they deliver a better outcome.

“Ukrainians have shown this to the point where everyone in the world is looking at drones differently,” Evans said.

The emphasis on cost-per-outcome was highlighted in Ukraine, where drones created an economic advantage by achieving favorable results at a fraction of traditional costs. This industrial advantage allows the smaller country to extend conflicts economically, mitigating the need for costly assets like tanks or scarce goods like shells.

“In extended conflicts like the one in Europe against peers, they come down to who has the better economy, the better production, the better economic engines. Unless you find a way to create asymmetries, cost-to-outcome asymmetries, like the Ukrainians did with drones, especially in the early part of the conflict,” Evans said.

Calculating how asymmetries will operate when these weapons systems are deployed is an essential problem. The bottom line is that there is no bottom line—yet. Planners cannot know in advance how much damage a military will likely produce by investing in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

If we could have tools for doing more careful analysis and prediction of where and what scenarios are going to be most highly effective, I think that’s going to be very helpful,” said Geir Dullerud, director of the Center for Autonomy, Grainger College of Engineering, University of Illinois.

There is little historical data to feed models and draw economic predictions. At this point, performance verification is part of a core data set that planners should have to weigh the expected impact of a drone in a war zone.

While unmanned vehicles have been available to militaries around the world for decades, the disruption of cheap—and equally important—accurate devices on the battlefield changed the game in ways not yet fully understood.

There is one point where analysts have found some certainties though.

“They took away [Russia’s] industrial advantages and gave themselves actually a lot of time to work with the West to create a new paradigm that people are still figuring out,” Evans added.

Since then, the electronic game of whack-a-drone has kept planners awake on both sides of the conflict.

“There’s been a lot of cat-and-mouse with the quality of the radio link and anti-jamming,” Evans said.

Incremental advances in electronics to relay data to and from the devices keep ordnance in the sky and battlefield intelligence flowing toward command posts. This may improve success rates in each part of the front until adaptation renders that improvement obsolete. Still, these developments are far from creating sustainable advantages for either side.

And math does not rule success in this arena. Advantages hide behind a trade-off between statistics and economics.

“You don’t need to be 100% as good if you’re 60% as good but at 10% of the cost,” Evans said.

A perfect outcome is unnecessary; achieving an optimal outcome is enough.

But just like Roman formations changed the warfare of antiquity over granular warrior groups, the arrival of individual unmanned vehicles is just a step toward the next stage of conflict.

Individual drones have become easy prey for countermeasures, electronic and kinetic. As Eastern European battlefields and towns are littered with the remains of devices that failed to accomplish their missions, a new formation emerges.

“A big part of warfare now with regard to UAVs is how well they can perform in a jammed environment,” Dullerud said.

The drone swarm is the direction where most in this segment of small-and-expendable UAVs want to go.

While true swarm behavior remains costly and technically complex, a “blind ballet” approach —where drones act independently but in unison—like drone light shows—could be an interim solution, offering coordinated action without direct inter-drone communication: “Act as a team even though they can’t maybe directly communicate,” Dullerud said.

Nevertheless, disruptions in communications will become increasingly common as nation-state adversaries improve their electronic warfare capabilities. Therefore, the next step is making each swarm member more capable.

“With the introduction of AI and machine learning methods, you can imagine that algorithms can be deployed,” Dullerud explained.

Leveraging advanced technologies, once these machines have clear instructions, they can improve mission outcomes despite many limitations.

“They may not be able to communicate with each other directly, or even with their home base, but they still may have vision sensors, other types of sensors, so they can ‘see’ what’s going on,” Dullerud said. A hypothetical drone equipped with computer vision sensors could coordinate actions without using radio communications within a swarm, much like insects collaborate.

Such technologies are in development; therefore, current formations lack such capabilities.

For now, the limitations to multiple vehicle operations are elsewhere for those deploying these machines in Eastern Europe.

The core challenge lies in manufacturing rather than technology, as producing high volumes efficiently is key. Ukraine’s approach of distributed final assembly for drones with components sourced from larger suppliers, enhances resilience by reducing logistical burdens and minimizing risks. This setup combines cost efficiency from large-scale production with distributed assembly benefits, which is critical in a conflict zone, explained Evans.

Therefore, deploying swarms at scale is a challenge in terms of technology as well as in manufacturing.

Comments