Valley of Death Phase Is Necessary

With the pace of technological advancements coming at a faster rate than even a few years ago, the process of weeding out less promising solutions is a necessary one, venture capitalists say. The U.S. military, which is leveraging more and more dual-use technologies employed by the commercial sector, also benefits from startup companies competing for funding and successfully negotiating the so-called “Valley of Death” paradigm.

According to Gordon Daugherty, co-founder and chairman of the Capital Factory, a venture capital (VC) firm headquartered in Austin, Texas, the failure of a startup to advance its technology, solution or prototype past the initial build or proof-of-concept phases is a common occurrence that he sees happening mostly before the startup is self-sustainable.

“Usually, there are multiple stages of evolution in the early days, where a startup is not scalable and not sustainable, and they have to raise money,” he said. “And in the seed and Series A stages there’s a big mismatch of supply versus demand. There’s not near as much capital available, as compared to the demand from all of the startups. It means that there is this weeding out. Only the good and great startups are going to get the funding. It means the so-so and not-so-great startups are going to die. And to me, it’s just a natural evolution.”

Another VC expert, Van Espahbodi, founder of Generational Partners, a new firm created last fall to foster deep or frontier technology, said the Valley of Death phase also applies to established companies. “The Valley of Death is nothing new,” Espahbodi said. “And it does not apply just to startups. It is more for those that struggle to raise funding. For any business to become successful in some kind of a growth, whether it’s seed stage venture, or late stage, private equity buyout, there is an interim phase of lacking profitability.”

As established companies grow and move to bring new technologies to the market, part of the investment cycle includes the J-curve, a rapid decrease just before a great gain, as they restructure or perform other crucial debt management actions to advance a capability. Here, some established companies succumb to the Valley of Death when they are not able to succeed past additional financing.

“Different companies require different types of investments,” Espahbodi said. “There’s public companies, like your Raytheons and your L3-Harrises. And then you have private companies like your General Atomics or SpaceXes. And on the public side, you’ll have different types of debt, restructuring and mergers and acquisitions. On the private side, you’ve got basically closed-door negotiations to secure a debt or to do some kind of leveraged buyout. The most extreme version of that private side is the venture capital side, which ranges from very early or pre-seed funding to growth stage. And when you talk about the J-curve, when you talk about the Valley of Death, what you’re really doing is shining a spotlight on private equity in general, whether it is an aged business that essentially gets leveraged, such as a satellite operator company, or it is at the venture capital early stage.”

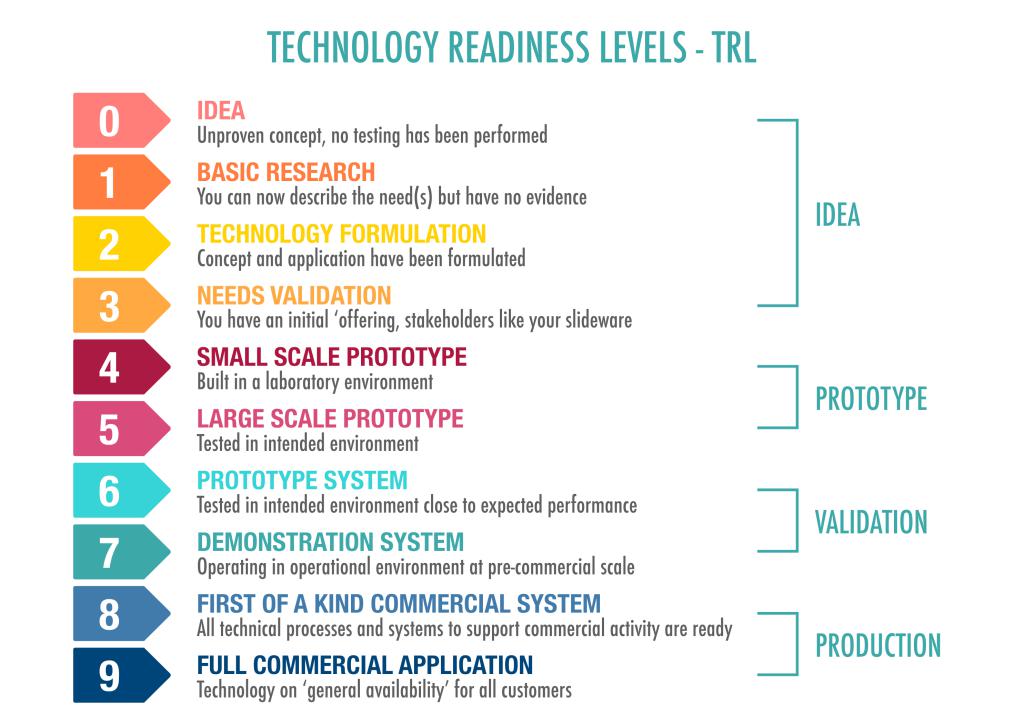

As startups and companies move a capability from idea to prototype and into further development, the Valley of Death phenomenon is common between technology readiness levels, or TRLs, of 4-7. At this stage, funding is crucial.

For the Capital Factory, they invest in companies with capabilities or prototypes at a TRL of 6 or 7, meaning that the startup has at least demonstrated the technology. Investing in the early stages of a technology’s development, “the seed stage and Series A stage, that’s mostly our sweet spot,” Daugherty shared. “If it’s hardware or something that’s a little more in the deep tech arena, or some kind of moonshot innovation, we’re probably going to invest even earlier, at TRL 4 or TRL 5, where they validated, but maybe not demonstrated, the capability in a relevant environment.”

In many cases, the startup is already generating revenue, especially with the software companies in which Capital Factory invests. With “moonshot” or groundbreaking technologies, they found the need to invest earlier because by the time that technology is proven and is generating revenue, company valuations already could be at $100 million or $200 million.

Naturally, a lack of funding can be a reason why a startup or a company fails to advance. According to Daugherty, the fundraising chasm most often happens before Series A investments. “It’s not that raising a Series A round of funding is a guarantee of success, but I see a dramatic difference in the startups that have raised a Series A,” Daugherty explained. “They have reached a level of maturity and repeatability and predictability that has resulted in the Series A investors giving them money, and now they have money in the bank, so they have time to keep executing. Their odds of making it get better and better after that Series A.”

Another challenge is that Series A investors are getting involved later and later, the Capital Factory chairman said. Startups may need to reach $1-2 million in revenue just to raise Series A funding, meaning they will need to get to that stage on other capital, either from angel investors or other seed stage VCs.

Besides funding, however, the experts see a plethora of factors attributing to the Valley of Death.

“Anybody that’s been in this movie before knows that there are many things that can kill a startup,” Daugherty noted. “We like to blame lack of funding as the main reason. Startups like to say that it is not them, it is not their business plan, it is not the market. It’s these crazy investors. There’s not enough money or your investors don’t get it. But that’s just one potential cause of death out of many, many, many.”

Sometimes it is the sheer commitment and attitude of successful companies that assist in carrying them through the Valley of Death. “The bold answer is they just want to get to work,” Espahbodi offered. “‘This technology is amazing, and we’ve got to get it out there.’ Sometimes it’s speed to market; who gets there first. And sometimes it is who does it better.”

The earlier seed stage may be particularly difficult, especially if startups cannot offer a lot of information for VC evaluations—if they have no [record] or a short track record of revenue, which may cause investors to pass on fostering a company. And here, startup teams—boards of directors, mentors and advisors—play an important part. Espahbodi warned, “Because it is going to be difficult to raise capital, it means you need to be more careful in how your team is formulated.”

Coachable founders are willing to bring on these mentors and advisors and listen to their angel investors. Cocky founders are not, and that’s another reason why cocky founders are going to kill the company.

Since a team can represent a variety of dynamics, Daugherty similarly looks to see if a startup team is driven. “Are they super passionate about the problem they’re solving? Are they smart? Do they have relevant experience?” he asked.

The personality and the experience of the individual entrepreneur is a factor. “For some founders, this is their first time running a company,” he observed. “And are they coachable? There are cocky founders that feel like they have all the answers—and cocky founders kill companies. Confident yet coachable founders have a better chance of success. So, when we evaluate a team, those are the things that we’re evaluating.”

Additionally, startups must have a sound business plan and a clear technology gap or problem they are solving by creating their technology. “Is the market for their solution a large and an interesting market? It is team, problem and market,” Daugherty suggested. “That’s what we have to look at.”

And because of how risky it is just getting to a million dollars in revenue, startups who make careless or unnecessary mistakes are also more susceptible. “Of course, startups are going to make mistakes, and startups are going to have to pivot. But if they do that unnecessarily, or if they are of an extreme nature, that can kill the startup,” he warned.

Daugherty advised first-time founders or entrepreneurs with less than 10 years of business experience to engage in an adroit mix of mentors, advisors and angel investors—specialists that can bring years of experience and wisdom to the table and help minimize mistakes and pivots. “And that can be the difference-maker,” he said. “Coachable founders are willing to bring on these mentors and advisors and listen to their angel investors. Cocky founders are not, and that’s another reason why cocky founders are going to kill the company.”

If a startup gets through the Valley of Death, it usually means the company has achieved some scalability, and they have also become profitable. “They might still choose to raise money once that happened, but they’re raising money because they want to, not because they need to,” Daugherty said.

At Generational Partners, Espahbodi is betting on frontier technologies—those of greater, nascent scientific advancement—and working on getting them commercialized and across the Valley of Death. “Deep tech, for me, is one of these niche categories that people historically treat as science fiction to science fact, a low TRL,” Espahbodi said. “But where the gap is, is that commercialization side of it, to go to market, when there’s this intellectual property ready to be put into a mission or to be sold into a certain customer segment. And what really needs to happen in these critical technologies that we are used to seeing in the defense industry is really to focus on getting to market and commercialization.”

Having helped pioneer a dedicated fund for the aerospace industry at Starburst Accelerator, Espahbodi is seeing the VC market specializing in more and more targeted funds. “You’re seeing national security themes rising with other investors, who are interested in dual-use [capabilities] and want to bring technology into the national security environment,” he explained. “You’ll see a crypto fund or a gaming fund or a real estate-dedicated fund or a climate fund, and now you’re starting to see artificial intelligence-dedicated funds.”

Espahbodi encouraged entrepreneurs to go after their technology visions and aim to successfully bridge the Valley of Death. “There’s never been a better time to ideate and venture into a new company,” he noted. “The most inventive and profitable companies were birthed during recessionary periods. I think now’s not the time just for what we call solo founders, but also for companies that bring compelling teams together.”

The Valley of Death is nothing new. And it does not apply just to startups.

Comments