Growing the Unmanned Fleet

In the last few years, the Naval Sea Systems Command, or NAVSEA, has made great progress in advancing the Navy’s vision of developing a family of unmanned surface vehicles and unmanned undersea vehicles, says Capt. Pete Small, USN, program manager, Unmanned Maritime Systems (PMS-406), Program Executive Office, Unmanned and Small Combatants, NAVSEA. The service is pursuing an aggressive effort to add unmanned vessels, as well as improve autonomous capabilities and the supporting open architecture that enables autonomy across various platforms.

“You could argue that the Navy has been pursuing unmanned technology for decades,” the program manager shares. “Then in 2016, the chief of naval operations (CNO), Adm. [John] Richardson, decided that we needed to consolidate some of the smaller unmanned efforts to try to generate momentum and the critical mass to move further downfield on deploying a real capability from a Navy perspective. And that’s when some of the efforts were consolidated into PMS 406. Since then, between 2016 and 2020, our budget has doubled multiple times, three times even, year to year. Over the past fiscal year, FY20, we’ve had our biggest year ever despite the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. We executed just over $900 million across three warfighting domains.”

And while some of PMS 406’s budgetary growth was the result of the consolidation, a larger part comes from an increased threat-based focus. “It is the growing understanding that we need to move toward distributed maritime operations, an architected fleet with a larger number of relatively smaller vessels including unmanned vessels,” Capt. Small notes. “The doubling of our budget that’s occurred a number of times has been new programs coming online and more money invested into the future for existing programs that are all aligned to that family of systems approach. It really has been a great period of expansion.”

In FY20, the command awarded three competitive contracts for the development of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and issued two requests for proposals to construct additional unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs). In addition, NAVSEA is fabricating 15 UUVs and 7 USVs. “Over the past year, we have also conducted in-water testing of USVs and UUVs on three coasts, sometimes at the same time, and despite the necessary mitigations to keep people safe from COVID-19,” the program manager observes.

For the rest of FY21, Capt. Small plans to act on the new contracts put in place last year and make additional contract selections for the construction of new autonomous sea vehicles. “There’s a lot of work to be done there, but we’re also increasing our focus on pilot programs for some of the advanced autonomous capability enablers in the areas of autonomy, data and command and control,” he says.

One pilot program in particular is the Rapid Autonomy Integration Laboratory (RAIL). As an ongoing effort through the rest of FY21, the RAIL concept relies on a software factory to provide the digital engineering, infrastructure, tools and processes to rapidly develop, test, certify and deploy new advanced autonomous capabilities, Capt. Small states. The pilot takes an existing autonomy capability, which was developed by the Office of Naval Research, and integrates it into an existing medium UUV, the Razorback.

“We do, in fact, need to look toward the future for when we have a family of UUVs and USVs, and we want to develop capabilities in parallel and outside of the actual platforms themselves,” the program manager clarifies. “That is where our concept of RAIL comes in. And we are working to budget for resources in the FY22 Future Years Defense Program budget to continue to build out that pilot into an enduring capability that is in support of our family of UUVs and USVs.”

The pilot is designed to develop autonomous capabilities as a set of microservices that use automated software, tools, services and standards that enable programs to develop and deploy autonomous applications quickly and securely. “It is progressing,” the captain reports. “We’re piloting each step of the RAIL process by which we bring in a new service, test it, do some software integration, test it again and then start testing it on the vehicle with hardware. We are somewhere in the middle of that process where we’re testing and integrating those software codes.”

By breaking out and examining autonomy into different software functions, the Navy can improve and advance the separate autonomous capabilities, from the basic UUV or USV operations—running the vehicle, turning the fins and the propeller, and performing simple navigation—to more complicated autonomous sensor operations. “That is one set of the software code,” he says speaking about the autonomy needed for basic operations. “And then there is a sensor package that’s associated with that vehicle, and each of those sensors has a bit of software that provides information, and then there may be payloads and there’s command and control that tie in as well.”

In addition, the service’s Unmanned Maritime Autonomy Architecture (UMAA), which the command has developed over the last several years, allows integration of new sensors or capabilities brought into the RAIL as a third-party capability if they meet the UMAA standard. “It can be integrated with the rest of the code, tested, certified and then put back on the vehicle,” the captain clarified. “The RAIL ingests all of those pieces of autonomy, not just the new micro service or autonomy capability.”

As for the various unmanned platform types in the family of systems that NAVSEA is pursuing, the portfolio for smaller unmanned systems includes both UUVs and USVs to use in the primary missions of mine countermeasures and oceanographic sensing. On the small, man-portable UUV side, “there’s really a wide variety of commercially available UUVs, and that opportunity grows every day as more companies become involved,” the captain emphasizes. “There is really great commercial availability of small UUVs and it’s just a matter of matching your mission requirements to a variety of options.” Presently, the Navy is prototyping two new small UUVs for mine countermeasures, expeditionary mine countermeasures and naval special warfare and undersea missions, he says.

While swarm technology—involving a series of smaller unmanned vehicles operating in concert—is a promising capability, it is something that the Navy will pursue in the future. “Ultimately, we’ll be looking for collaboration and conducting mine counter mission measures,” Capt. Small states. “It is a complex thing, and it needs a fully developed CONOPS [concept of operations] of generally small vehicles and how you launch or recover them and how they’re going to swarm to make an effect. We recognize the future prospect of that, but right now it’s not wholly focused on swarms.”

For medium-sized autonomous vehicles, the Navy is pursuing a number of efforts, also aided by a variety of commercial options. The vessels that the service is adding tend to be a bit larger, are more complex, have better sensors, offer more energy and more endurance—and are more expensive than the smaller systems, the captain says. The Mark 18, Mod II is a medium UUV for expeditionary mine countermeasures, while the Knifefish UUV has a specialized bottom and buried mine hunting capability to be deployed as part of the littoral combat ship (LCS) mine countermeasures mission package. The Razorback UUV, meanwhile, is an evolution of oceanographic sensing platform that has been adapted to submarine launch and recovery.

“All of those efforts are still ongoing,” Capt. Small reports.

The Navy’s portfolio of large autonomous sea vessels is experiencing the most growth, the program manager offers. The additional need for larger UUVs and USVs is driven by the current threat scenario with requirements to carry larger payloads over longer distances with greater endurance. “We’ve been working on a prototype for a Snakehead large-displacement UUV, which is also submarine launched and hosted, but designed to be larger for employment of bigger payloads, longer endurance and deeper missions,” he explains. “We are in fabrication of a phase one prototype and on the verge of issuing a phase two request for proposals for industry vehicles for Snakehead LUUV missions.”

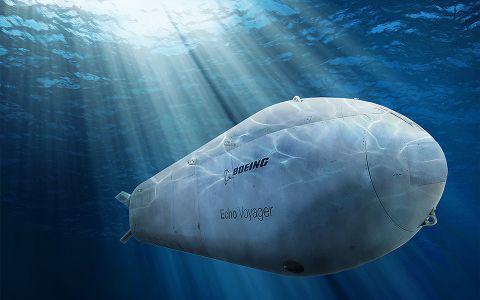

For extra-large or XLUUVs, the Navy is designing a pier-launchable vessel with a large payload capacity and long endurance for independent payload deployment operations. “Our primary effort there is called Orca XLUUV, and we have a contract with Boeing for fabrication of five prototypes that will be delivered over the next couple of years,” Capt. Small says. The power source for the XLUUVs is a diesel-electric propulsion plant, similar to a diesel-electric submarine, needed to support endurance levels measured in months and ranges measured in thousands of miles. The other unmanned systems generally rely on battery power, he adds.

Regarding USVs, the Navy’s effort for smaller-sized systems, which is called the Mine Countermeasure USV, is in low-rate production. The vehicle is a 12 meter-long modular craft that also will be LCS-deployed and will employ two different payloads: minesweeping and mine hunting. The minesweeping capability uses an acoustic and magnetic influence sweeping cable to check for magnetic and acoustically-influenced mines. The mine hunting payload relies on a towed sonar to watch for and identify mines for later neutralization. “There is a vision to have a future neutralization payload which is kind of like the third leg of minesweeping, but that’s still a few years down the road,” he notes.

Other efforts involving new medium and large USV capabilities are part of the Future Surface Combatant Force Architecture, advanced by the CNO’s director of Surface Warfare. That structure includes two manned platforms and two unmanned platforms, a large and a medium USV, and 406 is working on both, the captain notes. The service awarded a contract this past year for a prototype of the medium USV, a modular unmanned service vehicle—“a truck”—to carry a containerized payload. “Anything you can put in a container, you can put on the back of a medium USV,” Capt. Small suggests. “That vehicle also has requirements for relatively long endurance and independent operations. We are building a prototype now for that, and we’re heavily leveraging prior work that has been done by the Sea Hunter program.”

Finally, for large USVs, the Navy’s efforts have received a lot of attention from Congress. The service is looking to shift capabilities to respond to great power competition and sees large USVs supporting that kind of risk environment, Capt. Small clarifies. “The threat scenario from great power competition and warfighting scenarios clearly define the need for more capacity and more capability that can be provided by the concept of a large USV,” he states. “It is a large USV that is really envisioned to be an adjunct magazine or increasing the capacity, the depth of the Navy’s magazine in theater.”

In September, the service awarded six study contracts to six industry teams to help investigate specifications for a large unmanned surface vessel. “And we’re also heavily leveraging the Overlord prototyping program, which is using converted oil and gas fast supply vessels to really prototype a lot of the large USV capabilities that we’re looking for in the future,” the program manager notes. “There are a lot of conversations and effort and discussion there. But we’re making a lot of progress towards defining what is a large USV and working through the budget process and with Congress to continue to refine those plans.

“The whole reason why we have a family of systems approach is that one size, one common platform, either UUVs or USVs, is not going to meet the variety of mission requirements that we are working on for unmanned vehicles,” he stresses.

Comment

Hello

Hello

I retired 31 July, in Columbia MD. I was an Army Signal Corps Officer, then DOD Civil Service most recently ICAM ABAC PKI SME at Ft Meade and 3 years at USCENTCOM.

In retirement I intend to focus on environmental issues, including Invasive Species/ANS and marine debris, where UAV, UUV, USV and Swarm concepts will be a game changer.

There are two Executive Orders regarding invasive species, an ANS TF led by FWS, and many issues on and surrounding military facilities and operational environs.

As you can surmise, the USG could greatly benefit by leveraging work and somewhat parallel and unclassified requirements.

Is DARPA, other research labs, the USN, USCG, et al working on our proposing Case Studies for their Facilities Environmental Management?

Should the Navy lead a PEO similar to and icw CAPT Small?

I would appreciate further collaboration if desired.

Comments