Regular Technology Insertions Keep Critical System Fresh

|

The U.S Navy and General Dynamics Advanced Information Systems are using an open architecture, open business model approach to update the Tactical Control System (TCS) of the AN/BYG-1 Submarine Combat System. The process keeps technology state-of-the-practice and allows faster implementation of the best ideas for upgrades. |

The U.S. Navy continues to take advantage of open architecture and an open business model to incorporate the most advanced capabilities into a key piece of the Submarine Combat System. Navy leadership is employing a program where technology upgrades can be inserted as necessary and as available to provide sailors with the tools they need to perform their missions. The effort reduces the time between upgrades as well as implements the best new ideas in industry more quickly. The plan is benefiting tactical control on submarines by keeping technologies in a state-of-the-practice configuration at all times, while being responsive to requests from the fleet and lowering costs.

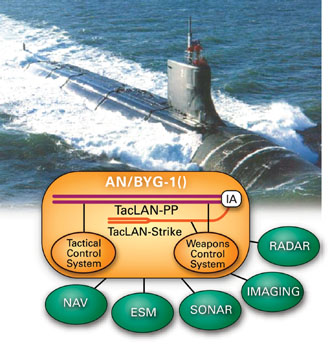

The submarine Tactical Control System (TCS) is the tactical hub of the various subsystems in the overall AN/BYG-1 Submarine Combat System. Capt. David Hahn, USN, program manager, Submarine Combat and Weapons Control Systems, describes the various subsystems as a spider web with the TCS at the center. “As a subsystem, it brings situational awareness for the tactical decision maker onboard ship,” the captain states. The system hosts the tactical local area network off which each of the other network systems hang. The specific purpose of the TCS is to provide submarine operators with all the information they need and to lead to good solutions for all the contacts the vessels encounter.

Capt. Hahn compares the situation in a submarine to driving down the highway and trying to navigate in a car with blacked-out windows. “That’s almost the nature of the world that we’re in when we’re submerged,” he explains. The TCS enables methods to display the various sensor inputs and outputs so crew members know where they are and what could affect the mission. The TCS also enables solution development and targeting information for the weapon systems.

The TCS and other systems remain on the cutting edge because of the open processes adopted by the Navy and its partners. The Navy implemented a process in which it passes requests from the fleet to industry and asks the private sector to develop solutions. When an idea looks promising, the Navy promotes it and ideally rolls it out to the submarines to solve problems. That same model is used for the entire submarine combat system, including acoustic sensors and processors, periscopes and imagery. The Navy modernizes the submarines by taking advantage of the unique opportunity through the in-place upgrade process to advance shipboard technologies about every two years.

In the process, the Navy upgrades the submarines’ subsystems in the federated system in an asynchronous manner. This allows the sea service to take advantage of new developments in one subsystem even if others are not ready for a change. The process requires a configuration in which the various subsystems and tools are not tied together.

For example, the navigation subsystem employed is not developed by the same organization that develops the TCS; Program Executive Office Integrated Warfare Systems (PEO IWS) controls the navigation technology. That navigation system also is not unique to submarines; it crosses a variety of platforms. Because Capt. Hahn’s office wants PEO IWS’s navigation capability incorporated into submarines, it needs to use a process where it can upgrade capabilities it controls at its own pace but still pull other developments from different sources and use them appropriately. “We don’t want to develop our own because they’re the experts,” Capt. Hahn says, “but we can’t demand that they upgrade their systems on the same pace we do.”

To tie it all together at the end, the Navy uses a standard interface for all the subsystems. Through this standard interface, Program Executive Office Submarines can use the data from the navigation system. The process and interface allow the office to use the best advances from the expert knowledge communities in the Navy to enhance submarine platforms. “That’s why we keep them separate,” Capt. Hahn explains. “We each respond to our community of users at the pace they need. And then we can bring it all together onboard submarines in a unique way.”

The piecemeal integration is part of the advanced processor build (APB) model the Navy uses. The APB is a process implemented to permit fleet-directed changes to tactical systems in a timely fashion. It is a collaboration between the submarine force leadership, the Chief of Naval Operations, Naval Sea Systems Command, academia and industry that identifies capability shortfalls, investigates relevant technologies, and develops and tests those technologies for fleet implementation. “So it’s a very dynamic process,” Capt. Hahn says. “It’s nothing that bakes for 10 years and then gets delivered. That’s the real beauty. We have a regular, steady drumbeat … [this] allows operators to do more work safely and effectively.”

APB also stands for a product, which is the combat system software version that contains new or enhanced capabilities applied as upgrades to existing baselines. A four-step process is used to validate the capability and make the technology ready for incorporation into the baseline system. The four steps are technology evaluation, algorithm assessment, integration and lab testing, and at-sea evaluation.

Capt. Hahn shares that using the technology insertion APB process model offers multiple advantages to the Navy. In addition to bringing capabilities to bear on a regular basis, the process also enables the Navy to avoid obsolescence issues. Submarines are commercial off-the-shelf-technology centric, so upgrades often are available for the technologies onboard. “If I were to ask you to go find spare parts for your 10-year-old computer today, it would be hard,” the captain explains. “We’re in the same position.”

Using the APB process, the Navy keeps hardware systems in state-of-the-practice conditions without acquiring new platforms. The builds also enable the Navy to take advantage of innovators’ ideas and provide solutions to the fleet more quickly. The upgrade process itself has been around for approximately a decade, and it still is critical for keeping technology current. New work on the efforts ensures advanced development continues on submarines’ systems.

The Navy recently awarded General Dynamics Advanced Information Systems $21 million for the first year of a multiyear contract to upgrade the TCS technology. As part of the contract, General Dynamics will reach out to small businesses to access the technologies and ideas available from other companies. The next build will take place at the end of 2011. Capt. Hahn says industry partners have been given the problems, and now solutions will be explored.

|

The Ohio-class guided-missile submarine USS Georgia, an SSGN vessel, passes Mount Vesuvius after a port visit to |

The open architecture and open business models also can apply to and benefit the construction of submarines. Advances leveraged for today’s vessels can extend to the new platforms. The Virginia-class submarine, for example, will absorb the same combat system used on the nuclear guided missile submarine, or SSGN, and Seawolf-class vessels.

Capt. Hahn explains that, through these commonalities, building the new platforms becomes easier because the different vessels are using the same combat system even as those systems are matured. “It’s really an exciting time for the sub force,” he states. An additional benefit of employing the same systems includes standardized training for crew members. Sailors can become familiar with one system and perform their jobs on various submarine classes, making personnel more portable. The business model also saves the Navy money because it leverages industry investment in capabilities, and the model rolls technology out to the fleet more quickly.

Some adjustments to various technologies, including in the TCS, are needed between platforms. Making sure that the TCS system is cutting edge across the classes is critical to the success of submarines. Mike Tweed-Kent, head of the Integrated Combat Systems Division at General Dynamics Advanced Information Systems, explains, “It really is about defending the sub through tracking targets and knowing in theater where the adversary is and being able to fuse all the information [the system] receives … to give the sailors the right tasks to successfully complete their mission.”

The open business model and open architecture approaches enable General Dynamics to encourage third-party investment and to take advantage of new developments for different customers. The U.S. Navy is not the only service pushing TCS into the future. The Royal Australian Navy has installed the technology on its Collins-class submarines.

General Dynamics has been working with the TCS since 2002. At that time, the Navy decided to make the TCS and the Weapons Control System (for which General Dynamics also is under contract) separate entities and apply the new business model to provide better capability for the tactical control function. The large private industry entity invites small businesses into its laboratories to demonstrate how their technologies function and how these technologies would fit into the larger processes and disciplines.

At the end of this latest effort, private industry will present the Navy with applications that can transition quickly into the fleet’s tactical control function. One capability of particular interest is to deploy an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) from a submarine to provide over-the-horizon situational views. The TCS would take the information from the unmanned sensor and present it to the sailors.

For the last two years, a government/industry team that includes General Dynamics as the AN/BYG-1 TCS integrator has been executing an Office of Naval Research Rapid Technology Transition project to integrate an unmanned aircraft system (UAS) controller into the system. On September 23, 2009, the UAS control capability with the integrated open unmanned mission interface UAS controller was demonstrated during live flight operations with a UAV. In addition to controlling the aircraft, contact information such as live streaming video from the UAV’s fixed camera payload was processed and displayed.

Another goal of the TCS effort is to incorporate more commercial off-the-shelf hardware by leveraging what the commercial market already is developing. According to Tweed-Kent, the key is to insert the hardware without necessitating changes to all the software. He says General Dynamics also wants to do the reverse action where it takes applications built by other companies and employs them. “The real tenet of open architecture is how to better do plug and play capability,” he explains.

The great advantage of the open business model, he shares, is about looking for the best ideas among different companies, working with them to test and validate ideas, and then bringing technology forward to the Navy in a disciplined process. In addition to industry ideas, the Navy also courts academia and defense laboratory input, and those organizations work together and with the private sector to develop solutions. Developers propose different sets of technologies and algorithms that can be brought to bear on the problem set.

Other future plans for TCS technology development include determining how to automate more information and broaden sources of information pulled into the submarines. Additionally, service-oriented architecture (SOA) capabilities likely will be added to the TCS. The Navy has expressed interest in the technology, and General Dynamics has been investing internal research and development dollars in future architecture concepts including SOA. The TCS team can use its understanding of the AN/BYG-1 and Submarine Warfare Federated Tactical Systems architectures to assist the Navy’s program office. The team can help review how these systems can be migrated to support better information sharing across all Defense Department sensors and assets.

Tweed-Kent also expects to see more intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information coming from hull sources integrated into the TCS system. Most specifics on those resources are classified.

WEB RESOURCES

PEO Submarines: https://acquisition.navy.mil/rda/home/organizations/peos_drpms/peo_subs

General Dynamics Advanced Information Systems: www.gd-ais.com

Comments