U.S. Navy Fielding Weather-Predicting Sea Drones

U.S. Navy scientists are fielding unmanned underwater drones which, when used with mathematical models, satellites and good old-fashioned brainpower, can better analyze the globe’s oceans and forecast. Ideally, the technology will predict what the world’s waterways will look like as much as 90 days into the future.

Look out military meteorologists. Might they be all but obsolete?

Well, no. Not yet, at least. But their duties are getting easier and better as technology improves.

U.S. Navy scientists are fielding unmanned underwater drones which, when used with mathematical models, satellites and good old-fashioned brainpower, can better analyze the globe’s oceans and forecast. Ideally, the technology will predict what the world’s waterways will look like as much as 90 days into the future.

Better predictions can help the Navy decide, for example, where better to park a ship to deliver humanitarian supplies after a tsunami or how to avoid radiation contamination if a nuclear power plant is damaged, Gregg Jacobs, Naval Research Lab scientist, says.

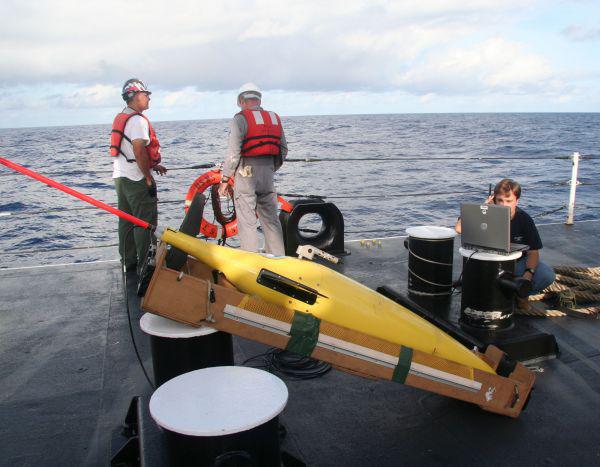

But for everyday use, the unmanned underwater submarines, or Slocum gliders, provide near-constant data such as ocean temperatures and salinity counts, information that can help sailor meteorologists better know how sound will travel or where strong ocean currents exist, Jacobs explains. Such information can aid toward marine mammal safety or assist in locating a missing object through sonar usage.

“Taking the uncertainty in the forecast into account is critical in operation decisions from tactical to strategic,” Jacobs says. “This tells planners where and when significant risk lies for the operations because of larger uncertainty in the forecast.”

The drone subs measure about 5-foot-long, can descend to depths of 4,000 feet and stay submerged for several months at a time, communicating data every few seconds or so, Jacobs says. The Navy plans to increase its inventory of the gliders from 65 to 150 by next year.

Universities have used such gliders for about a decade with much success, Jacobs says.

Atmospheric meteorologists predict weather about seven to 10 days out. Ocean meteorologists can give fairly accurate, educated guesses about 30 days out. Just think of the programming that can be done when planners can have a three-month future window. It’s a lofty goal, Jacobs says, but an attainable one.

Sailors with the Naval Oceanographic Office will get the training to know how to operate the gliders and dovetail the constant feed of data into their weather predictions.

On the commercial side, the Navy is sharing the drone technology and data with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which can use the information to help the fishing industry, for example.

Commercial vessels can better plan shipping routes around strong currents or eddies, and fisherman can use the data calculated from ocean temperature and salinity to “know at what depth to set tuna hooks,” Jacobs says.

Comments