Are Biometrics the New Intelligence Discipline?

The use of biometrics for force protection alone could be a bygone approach as the blossoming technology makes inroads toward the development of a new intelligence discipline. Biometrics intelligence ultimately could be the next INT in the menu of intelligence specialties.

The U.S. military’s interest in rapidly acquiring biometrics know-how to help today’s warfighter with tomorrow’s technology puts the private sector on the verge of a turning point.

Researchers at the U.S. Army’s Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC) have tapped various commercial products so that soldiers in war zones might reap the benefits of the promising technologies.

“The commercial industry has done a good job of pushing biometrics to the edge,” says Courtney Coulter, lead for the site exploitation team in the intelligence dissemination branch of CERDEC’s Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate (I2WD). “There is a lot of capability out there right now, and I’m very impressed with what the community has to offer.”

Program managers are seeking advanced analytics to support biometric and forensic workflows, improve data management and enhance interoperability while reducing the processing time to get critical data to troops, Coulter says.

Quick-reaction capabilities (QRCs) the Army fielded to aid warfighters during recent conflicts met requirements, but many were used for only a year or two. “QRC technologies developed during the recent wars are often not sustained because of shrinking budgets or a change in priorities,” Coulter says. “Additionally, many of the QRCs are never integrated into existing systems or cannot be transitioned to enduring capabilities for different reasons, usually because the system is too complex, the benefits do not equal the investment or the human capital costs are too high.”

Three programs CERDEC is pursuing seek to leverage biometrics from multiple repositories to give troops timely access to the data, analyze voice characteristics to rapidly pinpoint a possible foe and use surveillance camera images to identify enemies well before they near a base perimeter.

First, the Identity Resolution Exploitation Management Services (IREMS) program offers a technical intelligence solution that enables collaboration, data dissemination and active feedback at unprecedented speeds for the Army, says Coulter, who also serves as the program manager and system engineer for the project. Operators upload biometrics into the IREMS program using a Web interface and apply a streamlined workflow to receive results within minutes—a far shorter wait time than the manual match requests that take weeks. “IREMS is extremely affordable for the returns on investment, reduces human capital cost, provides new efficiencies and brings together a broad group of users,” she adds.

Since IREMS’ rollout in November 2011, engineers have made several enhancements. The program now lets users upload multiple biometrics files at once—making cataloging numerous individuals detained during a mission easier, for example. Soldiers can submit information directly to the Defense Department’s Automated Biometric Identification System (ABIS), a repository that can hold up to 18 million records of non-U.S. threat forces. Troops get direct access for timely identity verification. ABIS, which shares data with the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI, can process up to 30,000 transactions a day and is used for force protection; intelligence; physical and logical access control; identity management and credentialing; detention; and interception operations.

“IREMS was a temporary solution to a problem and has proved to be very valuable to a large cross section of the military,” Coulter says. “It is expandable, easy to deploy, user friendly, organizes data in visually consumable screens, resolves complex problems associated with disjointed networks, enables associates and foreign partners limited access to shared information, increases efficiency and simplifies the identity resolution process.”

The program supports a handful of U.S. military needs, including site exploitation, biometrics management, forensics tracking and case management, and can be configured to access data repositories managed by foreign governments or international organizations, if necessary.

IREMS will be integrated with the Distributed Common Ground System-Army (DCGS-A), a common system that merges intelligence collected by personnel in the field with open-source information gathered from social media. It is the Army’s intelligence component that “gathers intelligence spanning all echelons, from space to mud,” according to the program’s online fact sheet. Soldiers employ tools to analyze maps, process collected cellphone data, match biometrics and review full-motion video.

For now, IREMS speaks only English. “The topic has been discussed within the community of interest, and a skeleton prototype was developed, but there are no requirements to incorporate multiple language support into IREMS at this time,” Coulter says.

Another technology exploits voice biometric data to reduce the time it takes to identify individuals. Voice Identity Biometrics Exploitation Services (VIBES) takes the characteristics of an individual’s voice, such as speed, tone and accent, and builds statistical models of voices. The recordings are stored in a database, and the program uses mathematical approaches to overcome complications that might alter a person’s voice, such as illness, fatigue, stress or emotions. It can also filter background noises and account for poor conditions, such as a bad phone connection.

Soldiers use VIBES in combination with other biometrics to increase confidence when verifying a person’s identity, particularly because a person’s voice is more unique even than a fingerprint. Technicians process voice samples using automated audio engines, reducing the workload for humans. If an analysis produces unclear results, VIBES steps in and ranks the results so that analysts can focus on the most likely matches.

IREMS and VIBES address the need for speed, whether a soldier seeks to identify a potential adversary or run a background check on a job candidate at an overseas military base. “In the past, getting that data might have taken days or weeks, or maybe the [finger]print card sat for a long time,” Coulter says. “With solutions that are coming or exist today in the form of IREMS and VIBES … we are now able to provide answers much more rapidly. We’re not talking days any longer.”

A third program is Harvester, which is midway through a three-year effort to develop an automated system that can identify individuals by their faces using surveillance video feeds. “A lot of video is collected right now that isn’t being processed in an automated fashion,” says Karsten Reis, a forensic biologist at CERDEC. “Harvester is going to help process that video. It could help the soldier make a better decision down the line and reduce the burden on them watching videos.”

“Human beings can only recognize so many faces, but a computer can do that a lot better from video,” adds Keith Riser, a computer scientist and identity intelligence science and technology lead at CERDEC.

Engineers say Harvester also can overcome the issue of limited bandwidth in combat zones and alleviate the need to process data at higher echelons. “It will allow things to be done closer to the tactical edge, given this huge amount of raw video data,” Reis says. “Harvester can provide the intelligence for processing that data.” The program will analyze data from Army-owned security cameras or handheld devices. “It is agnostic to the type of video data and can process essentially any format of data, as long as it’s not in some proprietary format,” he adds.

Algorithms “teach” computers to see humans and differentiate a person from a vehicle or an object. “You do have to train the system and tell the algorithm what it’s looking for. For people, it’s all model-based—so you model something and say this is what a face looks like, this is what a car looks like, [and] this is what somebody walking looks like,” Reis explains.

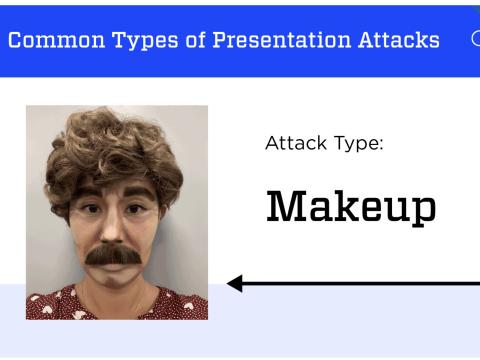

The software still faces challenges, such as returning a match of a man even if he shaves his beard. “If someone shaves his beard, it doesn’t mean [analysts] are back to square one,” Reis says. “However, the confidence that the person in separate images is the same is reduced.”

Similar video technologies provide better force protection by limiting access to the base. “If you’re able to identify the bad guys before they can target you, that’s the type of thing where video biometrics really help,” Riser says.

CERDEC wants to consolidate dispersed identity intelligence labs at its Maryland I2WD headquarters, reducing overhead costs and increasing capabilities. It would provide a central location where industry and military scientists and engineers could test products, Riser says.

The center, still in the planning phase, would focus on application development; technology and system integration; and data science and management efforts, such as data analytics and fusion, normalization, standards, testing, comparative analysis and multinational endeavors. No completion date has been announced.

Comments