Better Security Is in the Cards

|

|

| Patrick Grother is a computer scientist with the NIST Information Technology Laboratory, in charge of the biometric portion of the FIPS 201 update. |

The Personal Identity Verification cards used by every federal worker and contractor are being revised to address the technology advances that have occurred since the card standards were published in 2005. Changes are expected to reflect improvements in identity verification using biometrics and to address integration of mobile devices as well as to manage credentials in a more cost effective manner.

Each Personal Identity Verification (PIV) card carries an integrated circuit chip that stores encrypted electronic information about the cardholder, a unique personal identification number, a printed photograph and two electronically stored fingerprints. Along with being used to control access to facilities, some federal agencies use PIV cards with readers to control access to computers and networks. The Federal Information Processing Standards 201 (FIPS 201) ensures that the PIV card will be interoperable across the government.

The update to FIPS 201, which defines the operation of the PIV cards, is being managed by the Information Technology Laboratory (ITL) at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST expects to publish the final draft of the standard, which will be called FIPS 201- in the spring of 2013. The standard is currently in the comment period.

“The goal is to see if technology advancements and lessons learned can be incorporated in a revision of the standard,” according to Hildegard Ferraiolo, a NIST ITL computer scientist who is supervising the update to FIPS 201. Among the top recommendations that have been included in the revisions emerging from the public comment period, Ferraiolo points to expansion of PIV to what she calls “new form factors.” In their comments, federal agency chief information officers have asked NIST to modify FIPS 201 to accommodate the requirements of mobile devices.

“Currently, the PIV card is credit-card sized, able to be used successfully in desktop and laptop personal computers,” she outlines, explaining this is accomplished using scanning card readers. Without a port to which a card scanner could be attached, however, mobile computing devices and hardened identification technologies do not work very well together, she concludes.

One possible solution, Ferraiolo suggests, would be software-based: A secure application that would function as a PIV credential could be installed within the security layer of the operating system of an agency-approved mobile device. That credential, she explains, could be used to log into a task-specific software app on the smartphone or could be used to authenticate and log into a remote federal information technology (IT) server or web portal.

Still to be resolved, Ferraiolo says, are FIPS 201 guidelines concerning bring your own device (BYOD), an increasingly popular notion of the use of employee-owned mobile devices for official government work. Many federal information technology officials are advocating for policies supporting the practice, arguing that it saves agencies the up-front capital costs of acquiring the devices and allows workers to use tools with which they are already comfortable and productive. She says that BYOD may be addressed in a separate proposal for FIPS 201 depending on the quantity and nature of comments received in the next several months. Ferraiolo adds she does not yet know if the specification will deliver government-wide mandates or leave BYOD to individual agencies.

Another highly sought-after improvement in the PIV system is the ability for an agency to update and renew a card’s credentials remotely. Ferraiolo explains that this capability is being considered in the updated standard because certain cryptographic key credentials embedded in current PIV cards expire on a three-year schedule, compared with the six-year renewal cycle for the cards themselves. The current PIV system requires that employees report to their organization’s security administrators in person to update their credentials every three-years or whenever additional capabilities in response to a job change are added to a card. She says remote card updating is an effort to address agencies’ management of the growing number of teleworkers.

Input from agencies during the comment period has suggested that, “It can be costly for some of these workers to do in-person visits just for a one-time card update,” says Ferraiolo, especially for agencies whose cards are shipped from a headquarters office to a branch, or even to those workers who work full-time from home offices.

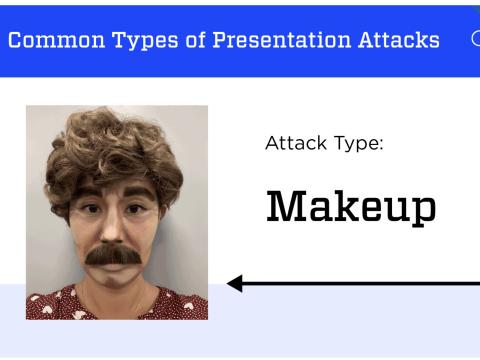

Another section of the FIPS 201 update now in its own public comment review period concerns biometric data that verifies that cardholders are who they say they are, going beyond the fingerprints and the photographs that are currently the main biometric component. PIV cards issued under the new specifications would include a scan of the card holder’s iris. The inclusion of an iris scan in addition to the photograph would facilitate better matching, according to Patrick Grother. Grother is the NIST ITL computer scientist who is editor for Special Publication 800-76- which is the biometric portion of FIPS 201.

“The new technology that’s come on the scene in the sensor arena focuses on iris scanning,” Grother adds, noting that the cameras used to scan irises have become mature, reliable products, capable of accurately capturing the unique characteristics of the human iris. In addition, iris scanning cameras are able to scan and compare a worker’s iris from a distance, which helps the flow of employees through security gates.

Even though incremental improvements in fingerprint technology have occurred, few changes are contemplated in this area. Grother characterizes fingerprints as the most mature of the biometrics now used in PIV cards, and they are also key to the interoperability of current cards across the government.

Facial recognition also is not expected to change substantially in the final FIPS 201 specification, says Grother, but agencies are likely to receive the go-ahead to include a new use for photographs. Automated facial recognition algorithms, used in conjunction with security cameras, would augment the current practice of security officers examining a card and comparing it with the face of the holder.

Grother says that, with the combination of a personal information number (PIN), fingerprints, automated iris scans, and automated facial recognition, federal security now will have the benefit of multi-factor authentication. A system that can confirm identity by more than one factor alone is much harder to compromise, he emphasizes.

The new biometric standard for FIPS 201 will also include revised standards for gathering biometric information when cardholders are first issued their badge. Among those will be a number of specifications that focus on equipment for iris scans, swipe fingerprint sensors, and also provisions to accomodate biometric technologies that emerge following final adoption of the FIPS 201-2 specifications.

As outlined in the draft specifications for FIPS 201- federal employees currently holding a PIV card would not be required to have identification credentials meeting the new standards immediately. The new standards would apply only to the stock of cards issued to new federal and contractor employees and to current employees as their credentials are renewed. This is being done as a cost-saving measure. Once FIPS 201-2 has been published, a transition period will occur to facilitate implementation. NIST is working with the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on implementation guidelines, and Ferraiolo says the current recommendation to OMB calls for a 12-month period. During this time, agencies would have to transition to cards and devices compliant with the new specification, after which all cards issued for new workers or renewals would need to comply to FIPS 201-2.

Some of the technical improvements that would become mandatory in FIPS 201-2 are now optional for use by federal agencies to meet agency-specific information technology security requirements as needed, Ferraiolo explains. “They would have to update their card management systems to implement those optional modifications with their current card stock,” she says, and when the final specification is published, issue a new card to an employee.

FIPS 201 is part of a suite of rules and regulations mandated by the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002. FIPS 201 is also legally required to conform to the control and security goals outlined in Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 (HSPD-12), a White House executive order with key policy mandates linked to homeland security. The FIPS 201 specification encompasses a number of special publications covering a range of technical topics addressing how the PIV functions: test guidelines for card manufacturers; interoperability at the same basic level all across the government; individual agency-specific technical specifications that respond to polices such as HSPD-12 hardware specifications for PIV system components, such as card readers; and finally, procedures for issuing the cards.

The enabling legislation to the original FIPS 201 mandates that the standard be reviewed every five years and an updated standard be initiated as a result of the review. The law does not specify when the revised standard must be published. In 2010, following its review, NIST determined that an update of the card standard was warranted.

Comments