Closing the Door on Iris Recognition Vulnerabilities

A simple capability found in most cameras may enable security experts to counter efforts by terrorists and other security threats to spoof iris recognition systems. The new approach focuses on eye function in addition to appearance, thus unmasking several types of deception that either would conceal a real iris or would fool a detection system into false acceptance.

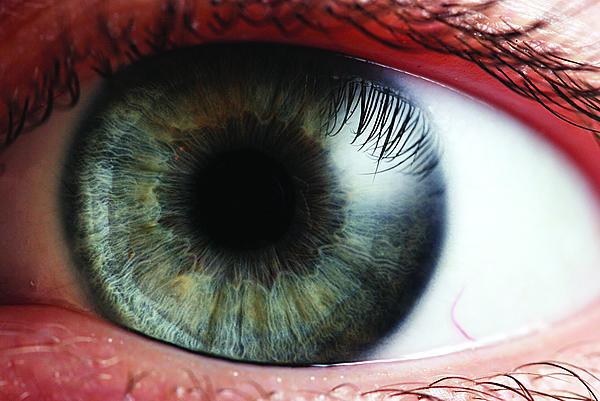

Iris recognition employs near-infrared or visible light scanning to record the pattern in an individual’s iris, which barring injury remains largely unchanged in a person from the age of 9 months. Near-infrared scanners reveal texture, and visible light shows pigmentation. Iris recognition systems can be used as security devices that admit only people whose iris patterns are cleared for access in a database, or they can be used to identify terrorists or other criminals who have been scanned and whose patterns already are on file.

However, these detection systems can be fooled by covering or altering the appearance of the iris. Criminals who want to avoid detection can wear a cover that conceals their incriminating iris. Similarly, someone who wants to impersonate a cleared individual at a security checkpoint can wear a fake iris that portrays the pattern on the original trusted individual.

The new counter to these and other types of iris recognition spoofing comes from one of the men who shares the patent for the original technique. Dr. Leonard Flom, principal investigator of biometrics and assistant clinical professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the New York University School of Medicine, developed iris recognition in 1987 with the late Dr. Aran Safir.

Flom describes five ways of spoofing iris recognition. The first way is to dilate a pupil to the maximum extent possible. This way, the iris pattern is not recognized by a scanner.

|

Is Bare Bones Identification Next? |

|

|

The inventor of iris identification is pursuing another approach to individual recognition that would work over distances. Currently, distance individual identification is the purview of iris, facial, voice and gait recognition technologies. However, individuals can mask these four characteristics with varying degrees of success.

Dr. Leonard Flom offers that one way around this is to employ skeletal identification. He describes how a synthetic aperture radar (SAR) design, for which he and a colleague hold a patent, can scan a person and define their skeletal pattern. Even a portion of the skeleton, which is as individual as any other identifier, can be enrolled in a database to track an individual. The penetrating SAR cannot be masked by the individual, Flom says.

Using radar to scan individuals raises safety and health issues, but Flom offers they can be overcome easily. Any of three factors—energy input, wavelength and time of exposure—can be adjusted to ensure an individual’s safety, he reports.

Currently, he estimates, this type of system could generate a resolution of about 1 centimeter. Flom expects to improve on this resolution after development of a prototype, which is not in the works yet. This will require funding, and he adds that he has been working to interest government officials in the United States and Israel in this method.

The use of this technology, which does not require the cooperation of a targeted individual, raises privacy issues. But Flom offers that the only people who would be enrolled in a skeleton database would be those who are incarcerated or are considered a security threat. As with his iris system, Flom is recommending that anyone who already is incarcerated should be enrolled with this and any other biometric identification in a database. People not enrolled in the database would not be identified, and specific legislation could ensure that information is not collected anonymously for future reference.

|

The second way is to place a dot-matrix contact lens with a fake pattern directly on the person’s eye. This would block the iris scanning system from recognizing an iris in its database, and it also would prevent that person’s iris from being entered properly into the database.

A third way involves a scleral lens with a painted iris on it. This type of lens covers the entire visible area of the eyeball, and a person wearing one would present the appearance of a completely different eye pattern.

The fourth method entails surgically implanting a colored iris in front of a person’s real iris. While many people who are opting for the surgery merely want to change their eye color, an individual who wants to disguise his or her identity can use this procedure. This surgery, which is being conducted in Panama, is not without risk, Flom relates. “He [the patient] would have to be out of his mind, because it is very dangerous to the eye,” Flom offers. “But there are people who are willing to sacrifice themselves in order not to be identified.”

The fifth way involves implanting a digital iris that fits in the original iris. Flom points out that this allows a person wishing to hide his or her identity to make subtle changes.

Flom states that all five of these attempts can be countered easily. The ideal way to defeat attempts by an individual to disguise his or her iris is to stimulate pupillary reflex, he says. “In each of these methods, if you shine a bright light into that eye, the pupil is fixed,” he explains. Either the actual pupil is chemically dilated, or it is covered by a false iris that is permanently fixed.

“If an individual is in the iris database and is trying to disguise his identity, he [or she] would use one of these methods to try to deceive,” Flom states. “But, if you shine a bright light into that individual’s eye, you would immediately detect that there is something in front of that individual’s eye.”

Flom continues that experimentation has confirmed the ability for the pupillary reflex approach to overcome spoofing in the first three methods. No research as yet has been conducted against the last two methods, but in theory the pupillary light technique should work against them as well, he says. The last two methods in particular, along with the scleral lens, may be adopted by individuals seeking to impersonate other people.

The type of light needed to trigger a pupillary reaction is neither complex nor extraordinary. Most single-lens-reflex cameras use a flickering light that fires just before the camera’s full flash kicks in. The flickering light shrinks the subjects’ pupils so that their eyes do not glow red from retina reflection, which used to happen with flash photos shot years ago. That same flickering light can serve as a pupillary reflex trigger in an iris identification system, Flom says.

An iris identification system with a light trigger would be reprogrammed to detect motion as well as iris patterns, Flom continues. This way, the system would be able to ascertain if the iris did not react to the light, and it would take that into account automatically as part of its verification.

And this light need not be embedded in the iris detection system, he notes. A simple handheld light wielded at the subject’s eye would have the same effect, and an iris scanner with custom motion-detection software would be able to detect a faux iris.

Flom offers that handheld iris scanners offer better precision than fixed systems. People of varying heights and ages have problems aligning their eyes with a detection system mounted on a wall or a pedestal. “Stand-alone [scanners] are notoriously inaccurate,” he states. “You should not be bringing the subject to the image capture device. It’s far better to bring the image capture device to the subject. The best way, by far, of capturing an image is handheld.”

Pupillary recognition should be added to all off-the-shelf devices, Flom says. For existing handheld devices, the penlight approach can be used to elicit a pupillary reflex. “The imaging device is the camera, but the holder of the camera is the one who detects the pupillary reflex,” he says.

Iris identification has the potential to supplant all other means of identifying a person, Flom offers. All that would be necessary is a standardization among all the organizations that require individual identification. Currently, too many different means of identification exist among databases for iris patterns to be adopted easily.

“If you use the iris as a means of permanent identification, you don’t have to know anything else about the individual,” he says. “That [iris pattern] would be the individual’s identity. You don’t need a Social Security number, or a picture or a [personal identification number]. That [iris pattern] would be your means of identification, and that’s going to happen within the next five to 10 years.”

For law enforcement, Flom is recommending that everyone who ever is incarcerated should have their iris patterns enrolled in a database, just as if they were fingerprints. That would allow easy positive identification of someone throughout their adult lives.

Adult iris scanning is not Flom’s only pursuit. He also is working to enroll newborn babies with their birth mothers into a digital identification system. The goal is to enroll their physical characteristics in the delivery room right after birth, and then their identities would be verified when they are discharged. This would prevent the rare but impactful problem of babies switched at birth.

The challenge lies with identifying the infant. A newborn’s iris is very amorphous, Flom explains, which prevents a scanning device from extracting any detail. The child’s iris does not begin to assume its adult characteristics until about nine months after birth, at which point it has taken on the appearance that it will keep throughout life. He notes that he is conducting research into how early an infant’s iris develops some identifiable features before that nine-month target.

For now, the solution to that challenge is to combine a scan of the mother’s iris with an image of the baby’s ear, Flom offers. This provides four different elements for a database: both of the mother’s eyes, and both of the newborn’s ears. This approach has been tested successfully in Israel, he relates, because the research requirements there were less sclerotic than in the United States.

This effort also demonstrated that any conventional off-the-shelf image capture device will work “We can use an iPhone, an iPad, even Google Glasses as well as any digital camera,” he observes. Adding a zoom lens allows imaging of fingerprints, palm prints and even faces without physically coming into contact with the person.

Comments