Creepy-Crawlies Aid Biometric Forensics

A recent study indicates the communities of microbes found in and on the human body can be used to identify individuals, much like fingerprints and other biometric data. The discovery could lead to a new form of biometrics supporting the identification of criminals and enhancing personalized medicine.

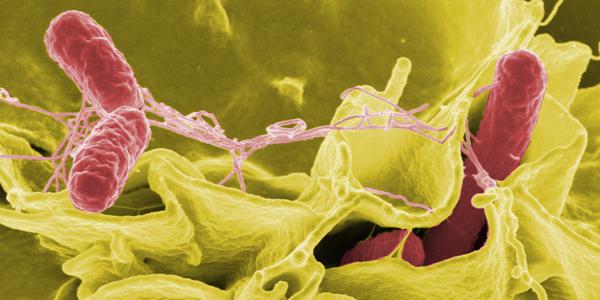

Microbial communities, known as microbiomes, exist pretty much everywhere on Earth. These communities consist of a variety of microorganisms, including bacteria and viruses. In fact, bacteria in an average human body number 10 times more than human cells and make up about 1 percent to 3 percent of human body mass. Many microbes are harmless, and some are even beneficial, producing vitamins, breaking down food to extract vital nutrients and supporting the immune system.

Now, researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health have revealed human microbiomes are diverse enough to provide a microbial fingerprint for each person. The study results were published May 11 by the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). The team demonstrated that personal microbiomes contain enough distinguishing features to identify an individual over time from among a research study population of hundreds of people. The study is the first to rigorously show that identifying people from microbiome data is feasible.

“The principle is exactly the same as human genetic profiling, where they get some DNA off of a sample or a crime scene, and then they use marker sequences in that DNA to try to match it against a database or to a particular person. We’ve shown the same kind of thing can be done with this microbial DNA,” explains Eric Franzosa, research associate in the department of biostatistics at Harvard Chan.

Franzosa, who led the study, and colleagues used publicly available microbiome data produced through the Human Microbiome Project, which surveyed microbes in the stool, saliva, skin and other body sites from up to 242 individuals. The authors adapted a classical computer science algorithm to combine stable and distinguishing sequence features from individuals’ initial microbiome samples into individual-specific “codes.” They then compared the codes with microbiome samples collected from the same individuals at follow-up visits and with samples from independent groups of individuals.

The results showed that the codes were unique among hundreds of individuals and that a large fraction of a person’s microbial fingerprints remained stable over a one-year sampling period. The codes constructed from gut samples were particularly stable, with more than 80 percent of individuals identifiable up to a year after the sampling period.

Still, microbiome DNA analysis is not as accurate as fingerprints and will not likely replace fingerprinting. Forensic techniques can be used to map the human genome to 1 in 1 million, for instance. With microbiomes, it was more like 1 in 1,000 in the Harvard study. “That means it would be a little harder to use it to uniquely pinpoint someone,” Franzosa says.

The technique could, however, complement current biometrics methods. “Because the human DNA forensics field is so mature, you would probably have to have a situation where this microbiome DNA is available but not the human DNA. I could see that as being a situation where you could use microbiome DNA instead,” Franzosa says.

Comparing a person’s unique microbiome markers with those found at a crime scene may be more helpful in identifying the innocent than the guilty. “It would be harder to say this person definitely is the one who matches a sample we found, or it definitely came from them, but you could use it to exonerate someone because you could say one person definitely does not match the sample,” he reveals.

Furthermore, microbiome DNA can reveal information about a suspect that other biometrics cannot. “The human genome is constant throughout your life. It can’t tell you where you were born or where you’ve been living the past 10 years, and there’s the potential for microbial signatures to do that,” Franzosa reports. “A microbial signature might be able to tell you this person was living in Southeast Asia for 10 years when nothing about their own DNA would indicate that.”

It is possible investigators one day could use handheld devices to process microbial samples, much like they now do with fingerprints and irises. “In the future, it would not surprise me if you could do that sort of sequencing in a handheld device. I think the technology to do the sequencing is getting down to that level of miniaturization, but it’s not quite there yet. The theoretical possibility is there,” he offers.

And the algorithm his team developed could prove useful on those future devices. “If you could do the sequencing in a handheld unit to actually figure out what microbial DNA was present on the surface or in a sample, then this algorithm would not be difficult to run on that device to potentially identify a person,” he states.

Future advances likely will include enhanced technologies for determining what species are present in a microbiome. “Now you sequence the DNA from the microbes, and then you try to match that to the databases of known microbes and their genes. As the profile of the microbiomes improves in accuracy and resolution, you’ll get potentially more stable [microbial] fingerprints, or fingerprints that are more stable across a larger population of people, because you’ll be able to see finer scales of variation that we didn’t have access to,” Franzosa predicts.

The technique does offer challenges because the microbiome is less stable than the human genome. “We know you can change it with time, so a person could, in theory, take antibiotics and perturb their microbial fingerprint, which might make them harder to identify. Or just natural day-to-day activity has some sort of perturbation effect on the microbiome. For some types, the microbiome is very stable, like the gut microbiome. It’s hard to disrupt. Others, like the skin, can be disrupted more easily, potentially by washing your hands with soap or [using] hand sanitizer,” Franzosa allows.

Science has not yet determined how long human body microbiomes remain stable. Franzosa’s team studied some participants for more than a year, during which the communities showed little change. “We don’t know directly from that [study] how that then scales to five years or 10 years and so forth,” he says, adding that longer-term studies are needed.

The next step for his team, Franzosa says, is to continue adding to the microbiome body of knowledge. “We would like to take that same algorithm and apply it to microbiomes outside of the human body. Unlike the human body, environments like soil, bodies of water, buildings and even trains don’t have their own genomes for identification, but they do have microbiomes. An interesting next step will be to see if those microbiomes can uniquely identify their environments,” he states.

The lessons learned ultimately could benefit the medical community as well. Franzosa cites earlier research done by others indicating that some microbes consume heart medicine. Patients who have that particular microbe end up getting a lower dose of their medication. “In the future, people will be interested in profiling the structure of their microbiome for that sort of purpose—to make sure their microbiome is compatible with the drugs they’re taking or the diet they’re about to go on. It will be useful for individual health in the future, in addition to this biometric application,” he suggests.

The findings also present privacy issues. The Human Microbiome Project databases used in Franzosa’s study were publicly accessible for researchers. Although names were not attached to the data samples, the team members found they could link microbiome data from a variety of databases to discover private and potentially embarrassing information about individual participants. “The kind of privacy concern there would be, say, learning that someone had a sexually transmitted infection, which is something they probably wouldn’t want to advertise,” he points out. “If the database only had microbiome data, you could directly learn that type of thing from it. If there is other sensitive clinical metadata, you might be linking to that as well.”

It is not yet clear why microbiomes are so unique to each person. “One possibility is that our own genetics may shape the bacteria that are successfully living on us. One species may be more successful working alongside my immune system, but if you put that into another person, their immune system would attack and destroy it,” he posits. “Different things—lifestyle, genetics and environment—affect it. We don’t know which one is the strongest effect yet. It’s definitely an active area of research.”

That research, of course, will continue to add to the knowledge of the “hundreds and hundreds” of microbes found in and on the human body, Franzosa says. “And those are just the ones you can find names for. There are probably lots in there that we don’t know about,” he adds.

Comments