This Team Is a Lean, Mean Cyber Crime-Fighting Machine

Modern information and networking technologies bring exciting functionalities to everyone, everywhere, all the time. Manufacturers, service providers and users alike welcome the advancements because they boost business opportunities and enable new and better computing capabilities that offer convenience, increase independence and save time.

Plainly, innovations are appealing, but important security aspects are being pushed into the background. Security adds complexity and limitations to functionality. It requires more resources and seems to slow innovation and increase cost. In a military environment, these hurdles can seriously affect mission success.

Security measures also have flaws that can be exploited by hackers—the greatest threat to cybersecurity. In today’s cyber wars, the best hackers are selected, trained and deployed not only by financial and economic competitors but also by states through their militaries and intelligence agencies. In addition, hundreds of thousands of so-called script kiddies try their luck with ready-to-use hacking tools found on the Internet.

Seemingly, this problem can be solved by specialized security technologies. A range of advanced and sophisticated security technologies is available, including firewalls as well as anti-virus, intrusion-detection or security information and event management software. These technologies, often combined and configured in different ways and based both on rules and heuristics, try to find security-related events automatically and issue alerts, possibly even blocking presumed attacks.

But they are not cure-alls, and well-trained human-machine defense teams can stop cyber crime better. Despite the availability of specialized security solutions, security issues remain and new ones arise. This could be caused by new protections that are often layered atop previous solutions. Because innovations emerge virtually every year, the entire security infrastructure is in a constant state of change, leading to inconsistency. Consequently, the security environment resembles one large, complicated construction site that is prone to errors.

To address this problem, even more sophisticated technologies have been developed to evaluate the combined information from different security layers and network traffic types. However, unlike firewalls, new solutions such as network behavior analysis, security information and event management or deep session inspection require constant, highly dynamic tuning and attention from trained operators. If unmonitored, they either issue too many false positives or lose their effectiveness.

Overreliance on technology can cause another problem: It gives rise to a false sense of security that leaves cyber warriors unable to face an attack. Unfortunately, an attack may be detected only by its impact, such as when exfiltrated data that was thought to be protected is sold on the Internet or when physical infrastructure is damaged. At this point, it is too late.

But many steps take place between a hacker’s first intrusion attempts and the last action on the target, and fending off an attack is possible with a team of defenders instead of a team of observers. A key element of protecting systems is knowing how to counter an ongoing attack, which may entail containing an attack to prevent or minimize its impact.

The human factor is important in this equation. It is vital for defenders to know their enemies—especially how they think. Attackers know very well how to exploit the vulnerabilities of security technologies. Furthermore, they are aware of how unprepared many organizations are to react to an attack or even coordinate efforts. Hackers try to get in where they are least expected. If defenders do not know how a hacker thinks or acts, then they will only be in an onlooker’s position.

It is important to train hard and fight easily. Security administrators and operators rarely have the opportunity to experience a real-world cyber attack in all its phases. Nor do they have the chance to counteract such an attack after a successful infiltration into a network. A key issue is whether defenders can act using their technical and analytical skills and according to an incident response process that covers all the escalations and decision-making steps that data defense involves.

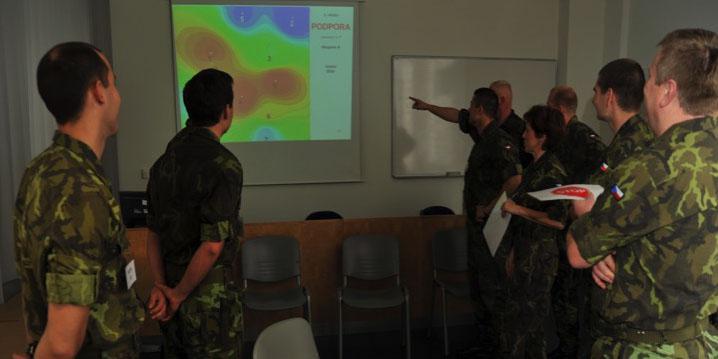

The military offers valuable lessons in this realm. All armies know that, in addition to arms and equipment, their soldiers need regular training. No army deploys soldiers as individuals; instead, they fight as a team. A group of skilled people must be able to learn and work as a trained team, which is more valuable than a single cyber guru. Team members can share and combine knowledge, coordinate action, support and fill in for one another, and split focus.

This is not only about education in the form of knowledge gathering but also about real skills. The only way for a security team to prepare for a real-time attack is to face one in real hands-on training where, led by instructors, the team can experience and fend off actual hacker attacks. This type of training applies to the technical security team and to the decision-making hierarchy.

New times call for new methods to create effective civilian and military teams. The last century was a period of wars with mass deployments of troops of all kinds on broad fronts. However, the world’s present military-political situation requires a changed view of the way combatant operations are conducted. Interest is shifting to small- or medium-size military units, as evidenced by the experience of coalition forces in the Balkans, former Yugoslavia, Iraq and Afghanistan. Hybrid wars represent a struggle on the ground and water and in the air, space and now cyberspace.

Sociomapping is one method to create effective teams in this new domain. Cybersecurity managers at all levels can use this method for mapping relationships and links within teams during both war and peace. For many years, the Czech army diagnosed social groups using sociomapping, which Radvan Bahbouh, founder of QED Group, created and developed in the 1990s. It provides a clear and comprehensive expression of mutual interpersonal relationships and connections in groups.

The technique has been used in a variety of situations where it was necessary to analyze relationships within complex systems ranging from small groups to populations, armies and civil institutions. Now the method has found its place in teams that are training to defend against cyber attacks from an extremely powerful and completely unpredictable enemy.

The approach can be used for selecting individuals for teams as well as for self-monitoring the dynamics of relationship development and links in a specific group. Evaluating an individual’s affect on group cohesion, which is one of the important preconditions for successfully accomplishing both combat and noncombat tasks, can be crucial to overall mission success on both the physical and cyber battlefields.

New types of attacks need new defense methods. Technology as a tool in the hands of well-trained defense teams designed as collaborative units not only protect systems but also prevent cyber attacks before they happen.

Milan Balazik, CISSP CISA, is an information security specialist and a training arena manager at CyberGym Europe a.s., a cybersecurity training facility. Col. Katerina Bernardova, CZA (Ret.), is a psychologist, researcher, consultant and coach at QED Group a.s.

Comments