Intelligence Community Poised for Revolutionary Change

Having too little information once daunted the world of spies and intelligence analysts. Now the problem is too much data, and one of the biggest challenges going forward for the intelligence community is not a lack of technology but civilization’s dependency on it.

Today big data is one of the hottest segments of the information technology industry, successfully shrinking the world while creating an information overload that can paralyze analysts working to win the data-management war, experts lament.

The deluge of information taxes an already strained intelligence community grappling with many other challenges, from growing cyber concerns that threaten national security to shrinking budgets, creeping commercial competition and a millennial generation struggling to prove that it can succeed in the work force, to name a few.

The broad world of intelligence—already so complex—is becoming ever more convoluted.

“As we move forward, what’s interesting is the more connected we are, the more disconnected we are as individuals,” offered Alex Anyse, a former human intelligence operative, during a recent AFCEA panel discussion on trials the community faces. “We have a generation of folks who have grown up in the technology environment. Everywhere you go today, you leave a footprint. Everything you do leaves a footprint.

“Today’s generation thinks it’s OK to have 45 friends in China through Facebook. Do you know them?” continued Anyse, now a partner with the MASY Group LLC, a provider of high-impact national security, intelligence and private-sector capital management solutions.

But members of this technology-driven generation, often chastised for their inability to hold a decent conversation, mirror their peers across the rest of the world—and they might have more to offer than meets the eye, counters Keith Masback, CEO of the U.S. Geospatial Intelligence Foundation and one of five experts at the panel presented by AFCEA’s Emerging Professionals in Intelligence Committee (EPIC). “They are very capable of operating in that [technology] environment,” he says.

Masback highlights an environment successfully exploited by multinational terrorist groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which governments have indicted for radicalizing numerous youths in several nations. Experts say ISIL excels at using propaganda to lure young people either to travel to Syria or Iraq to fight for the group or to convince them to carry out killings in so-called “lone wolf” attacks, which have taken place in various countries this year. ISIL leaders never have to actually come face to face with the youths, instead recruiting and convincing them to kill others via the Internet, Masback points out. “[They are] communicating electronically,” he says. “Those skills are very valuable for understanding how to operate in that world, which is their world. [Millennials] bring valuable skills to us, even as we recognize and lament some of the things they may not have. We ought to treasure, value and learn from the things they are bringing into our work force.”

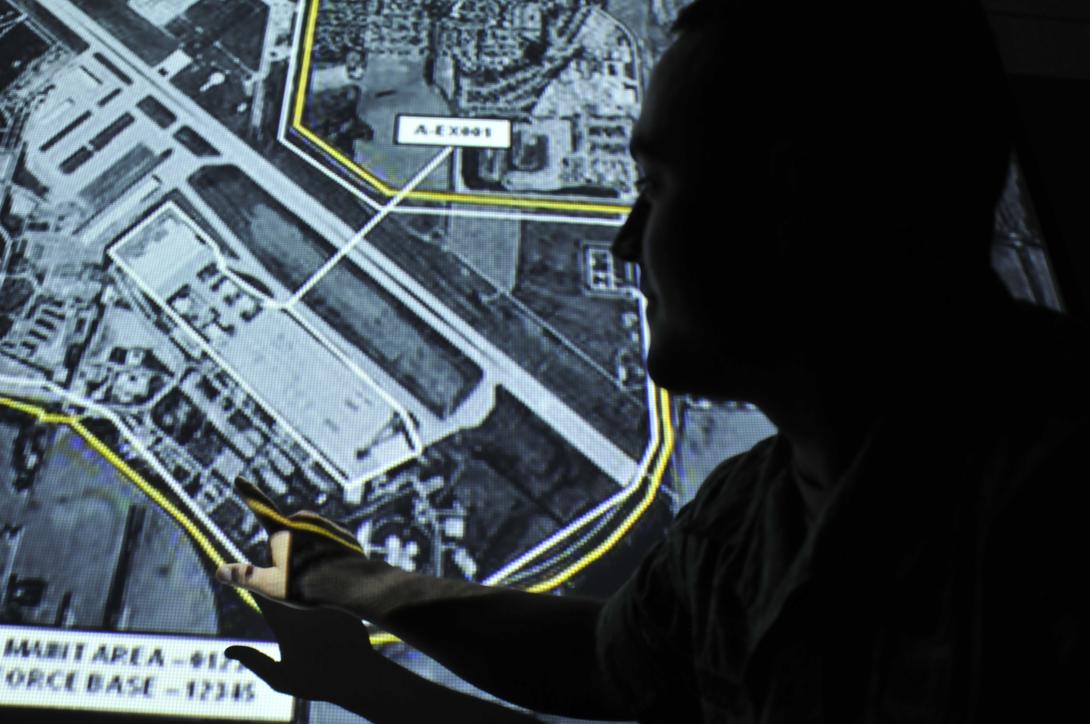

The composition of the future work force is just one of the flavors of fundamental change influencing the intelligence community. Still, these changes might not mean all doom and gloom for the future, offers Masback, a former U.S. military officer who also served at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency as director of the Source Operations Group and at the Office of Strategic Transformation as deputy director. “There’s a revolution going on in geospatial intelligence,” he says. “This is at once the most exciting thing that’s going on with respect to GEOINT [geospatial intelligence] and the biggest challenge. It is sort of like the Wild West.”

Private industry today not only has access to some of the most sophisticated technologies once reserved for the clandestine community, but it also is more likely than not the manufacturer of them—often at substantial cost savings to the government. Years ago, analysts might have balked if a gas and oil company representative, for example, inquired about the merits of using electro-optical sensors versus radar sensors to learn if a competitor erected a decoy drilling or exploration site. That is not the case anymore.

“This is a perfectly reasonable conversation to have today,” Masback offers. “There is a geospatial-intelligence revolution going on, and it’s perfectly reasonable for a company … to have access to radar imaging, infrared imaging and electro-optical imaging and multiple different flavors and choices from space, from UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles] [and] from the ground.”

The revolution hitting GEOINT will transcend the other INT disciplines coming of age. The reliance on commercial providers by the once closely guarded federal space of signals intelligence (SIGINT) is “one of the things that I think is coming down the road for the NSA [National Security Agency],” says Maureen Baginski, former SIGINT director at the NSA and who served as the FBI’s executive assistant director for intelligence. Just as GEOINT has acknowledged the role of commercial providers, she adds, “I think the NSA and other SIGINT entities are going to have to come to grips with that.”

Open-source intelligence, or OSINT, often is overlooked and underappreciated for the important part it plays in intelligence operations. “Open source is sort of like Rodney Dangerfield. It don’t get no respect,” quips Mark Lowenthal, president and CEO of the Intelligence and Security Academy LLC. He has served as the National Intelligence Council’s assistant director of central intelligence for analysis and production and vice chairman for evaluation as well as deputy assistant secretary of state for intelligence.

Just defining OSINT and including it within the intelligence community proved to be tremendous challenges, says Doug Naquin, a retired CIA senior executive who was also the first director of the CIA’s Open Source Center. “More people saw open source more as a commodity, like stuff you can buy or don’t buy, than as a discipline,” he says. But information need not be secret to be valuable, and the tidbits gleaned from browsing blogs, watching broadcasts, scanning social media sites and more must be put into usable context to provide meaningful intelligence. “Open source is publicly available information [that is] legally accessible. The intelligence part is applying that publicly available information to actual intelligence problems and questions,” explains Naquin, who is now president of his own company, the Open Source Software Institute. “That’s the tough part when your universe is increasingly expansive … but your resources are still finite.” Figuring out how to manage big data complications effectively and getting away from seeing open source as a commodity instead of a discipline are two OSINT challenges, Naquin adds.

“If I were queen for a day … I would actually change the whole construct of the intelligence community and the core capability,” Baginski interjects. “The first thing we would use is open source. And then [the other INTs], with our secret stuff and our sources and methods, would fill in the gaps.”

Today’s information environment offers too much data that is often too hard to understand, she adds. “The information environment has completely changed, and we do have to recognize that we may not know what is secret anymore,” Baginski says. “There is more information that is outside of us for the first time than inside of us.” Grabbing the entire haystack just in case there is a needle in it no longer will be an effective way to do SIGINT, she contends. “I do think we have to come to grips with a better, more effective way to surgically extract what you need from those networks and systems using other sources and the integrated intelligence community.”

Experts seek more effective ways to safeguard the cybersecurity realm as well, particularly in the wake of government data breaches that compromised so-called “crown jewels material” from security background checks and the personal data of millions of federal employees and their families. The onus falls on federal cyber experts. “We haven’t done the fundamental analytic work of deciding what the strategic sanctuary is, building countermeasures there and moving out from that,” Baginski states. “Until we do, we’re going to throw a lot of money after bad, not unlike the way we prosecute the terrorism target.”

The nation has not given cyber serious thought, Lowenthal declares. “We have littered [the Department of Homeland Security] with homework assignments, none of which will come in on time,” he says. “Each of the services has a ‘cyber command,’ and then we have Cyber Command. Why? Because people can smell money. What we don’t have is a serious strategy for cyber.”

Comments