Data Won’t Solve Everything, But It Will Help

In March 2025, President Donald Trump announced a headline initiative to restore America’s maritime dominance. This effort presents the opportunity for a change in how the United States promotes its maritime economy and prepares its maritime industrial base to support historic levels of power projection and defense. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) continues to pour valuable resources into recruiting for its sea services. As these various missions within the executive branch are looking for capable Americans to fill their ever-increasing billets, now is the time for intentional and deliberate cooperation and collaboration across organizational lines as part of a whole-of-government approach.

Earlier this year, the acting assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy for research, development and acquisition testified before the House Armed Services Committee, explaining efforts to date to supplement the maritime industrial base, while successful in some aspects, were encountering significant headwinds in the area of retention of skilled workers. The maritime components of the DOD are likewise encountering struggles in retaining talent, and all parties involved are struggling to recruit enough qualified individuals to carry out these critical missions as we approach the threshold of the Davidson Window. There are high-quality individuals who separate or retire from the Navy or Coast Guard every day, and these former military service members are looking for their next chapter. In addition, Military Sealift Command has had to place 17 vessels in extended maintenance periods because it does not have the crews to staff them.

What is one thing that each member of all of these groups, including those who just apply to join these groups, has in common? They have a desire to serve a mission bigger than themselves.

While each of these organizations has its unique challenges, their needs intersect in such a way that sharing personnel and recruiting data among them could help close the gap in a much more timely manner. For example, some estimates indicate that the Navy has 80 unqualified candidates for every sailor who gets on the bus to boot camp. With a target population of approximately 40,000 recruits per year, that leaves hundreds of thousands of people at least somewhat interested in serving their nation—but their data stops with the Navy.

If the Navy were to share that data to a central repository, then there may be a better match for those individuals within the U.S. Coast Guard, Military Sealift Command or the maritime industrial base.

If the Navy were to share that data to a central repository, then there may be a better match for those individuals within the Coast Guard, Military Sealift Command or the maritime industrial base. What if all of these organizations were to share recruiting data on individuals not brought into their organizations with each other? Would an additional pool of candidates who have already expressed a desire to serve their nation not be a benefit to each of these organizations?

While these organizations all have work to do, from culture to infrastructure to pay and benefits, starting with a group of people who see a bigger picture and are called to a purpose would likely show benefits downstream from the perspectives of recruiting and retention.

Stratascorp Technologies proposes the development of a collaborative framework in which various government and public-private organizations share recruiting and personnel data for individuals they will not bring into their respective organizations, for whatever reason. Due to the national security mission of these organizations, along with the maritime nature of their work, enough commonality exists to believe the initial recruiting work of one organization could benefit another. As we are talking about personally identifiable information, of course the data must be handled properly within appropriately accredited systems, and individual candidates should consent to the release of their data. However, data sensitivity and handling requirements should not hold up the rest of the conversation of how these organizations can help each other.

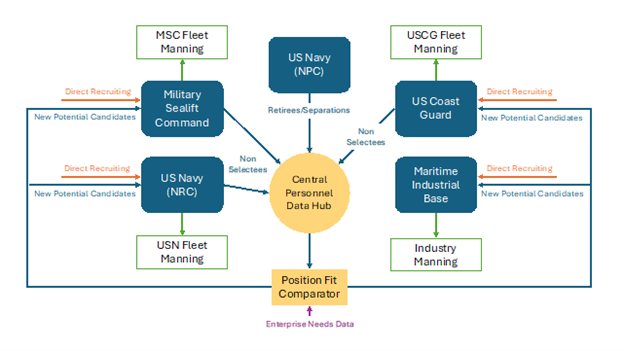

Figure 1 conceptually illustrates a potential ecosystem and data flow for the proposed framework, which could be expanded or contracted, based upon needs and performance over time. In this situation, the Navy, Military Sealift Command and Coast Guard provide recruiting data into a central personnel data hub. This hub would take data from each organization’s existing personnel systems via application programming interface and standardize and structure the data such that each individual record can be queried for any opportunity within any of the participating organizations. Due to the sensitivity of personnel data from its private-sector entities, the maritime industrial base would not contribute data to the central personnel data hub. However, the industrial base would have access to the information provided by other public entities to determine whether a fit exists throughout the thousands of entities within the private sector. A position-fit comparator would take each individual personnel record and evaluate it against each vacancy available throughout the enterprise, providing a suitability score for each individual to every participating organization.

This software and artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled methodology would streamline recruiting efforts, providing organizations throughout the maritime enterprise with credible candidates that they would have each had to otherwise organically source themselves.

For the United States to keep pace with power competition, disparate organizations throughout government departments must work together to find the right people for the right roles. By sharing data about individuals who have expressed an interest in public service but are not the right fit for one organization, other maritime organizations may benefit.

Providing a sufficient workforce for all U.S. maritime needs must be a collaboration among organizations. A central framework provides a common environment for those organizations to share information and move the mission forward.

Scott Sloan is the president and CEO of Virginia Beach-based Stratascorp Technologies and is a retired submarine officer. At StratasCorp, he oversees the operations and growth of the 300-strong workforce deployed around the globe.

Comments