On Point: Q&A With Daniel Goldman

What do you mean by “robo-physics”?

We started realizing what we were doing was enough that it wasn’t quite robotics as traditionally defined. We called it robo-physics because it was taking the robots and treating them as interesting objects to study. At the same time, we could think of these as robo-physical models for the animals.

One of our first was a sand swimming lizard. Once you make a robot model, it teaches you some things. What are some good and bad ways for it to swim through sand? How should it bend its body? How should it use its limbs? These things have just become an infestation in my lab. There’s more robots than animals, and that’s in large part because they’re easier to work with.

Bio-inspired robotics is an old term at this point, 20 or 30 years old. This approach of the physics of robots, robo-physics, is much younger and something we came up with. I think it has a nice reciprocal back and forth between the biology and the physics, and as an output, tends to make very useful engineered products.

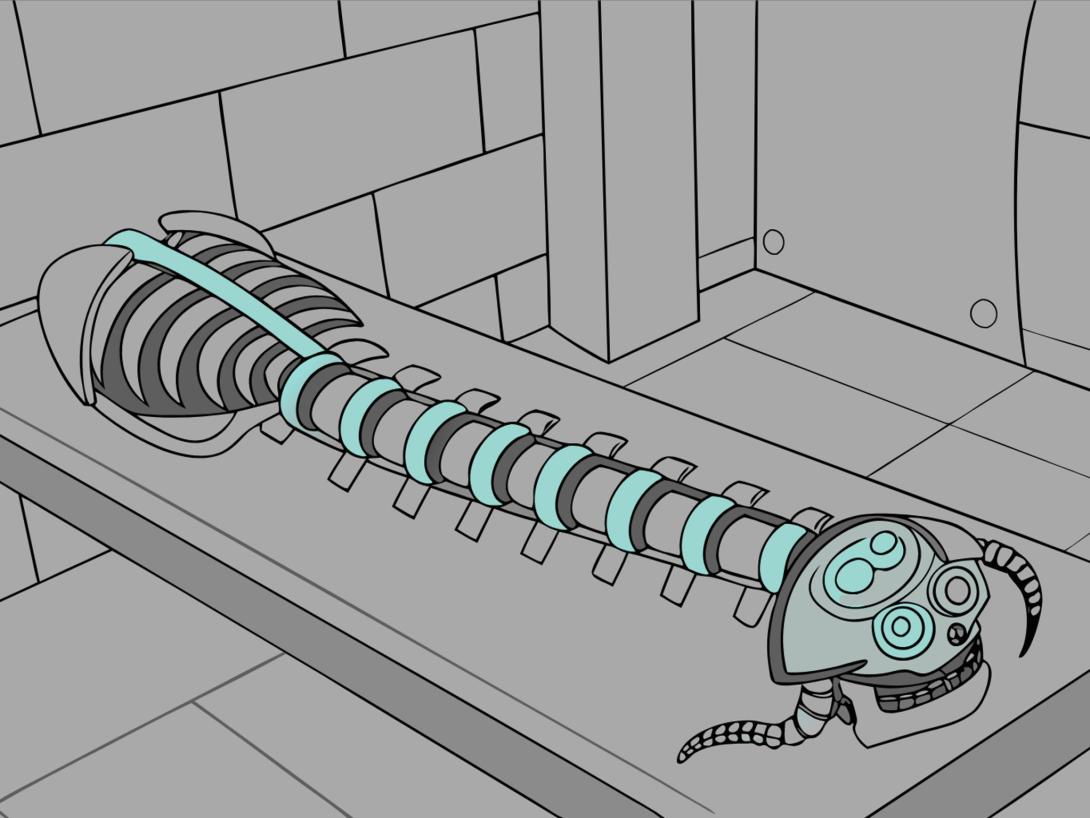

And that’s what we’re doing with my company. We studied centipedes, long story short, and found that our robo-physical models of centipedes were remarkably capable outside the lab. And from there, we started trying to understand why they were so good and whether we could use these in potentially commercial applications.

The answer looks like it’s probably going to be yes.

What role do you see artificial intelligence playing?

AI is a name for, let’s say, more computational heavy control. AI can potentially help you understand the world and then act on it accordingly; however, and it can also help you with learning-type systems. But at this stage for us, once we have what we call the “mechanical intelligence,” then we can bring in the computational intelligence, and then marrying those things produces really capable devices. I don’t even like to say that we have AI, because the whole system is artificially intelligent and capable. People are now calling this physical AI, whatever that means.

Are there some ways in which the robotic centipedes are an improvement over nature?

We can command the robots to do things that the animals could never do. Now, to a good approximation, the animals are basically infinitely capable. They can do things which no robots can do and probably will never be able to do in our lifetime—just my bet. Animals have hundreds of muscles and millions of neurons, and lots of sensors everywhere. The leg of a centipede is filled with sensory apparatus, and our robots have 10 motors on their backs—pitiful.

That said, with some of the control principles we’ve discovered and some of the mixing and matching, we can make a sidewinding centipede. Centipedes, you know, use their bodies and limbs to move around kind of straight. There’s a certain snake we’ve studied, a sidewinder rattlesnake, which lives in the deserts and moves really well on sand. We can combine sidewinding and centipeding and get really crazy performance that no one’s ever seen.

Is there a term for that kind of robot that is a hybrid of different animals?

We’ve been calling these things, for lack of a better term, “multi-legged, elongated robots,” MERS. Not the best name, but it’s this long, skinny robot profile, plus legs, and seems to have some real interesting capabilities.

This column has been edited for clarity and concision.

Comments