Learning Online From the Front Line

Distance education programs allow soldiers to pursue knowledge, sharpen warfighting skills.

The U.S. Army has actively entered the distance learning arena with two programs that allow soldiers to earn college credits or improve their military occupational skills online from their primary bases or while deployed.

In an era of sophisticated weapons and communications systems, technologically savvy troops are a necessity. By providing training and instruction online, updated information can be disseminated quickly to widely deployed forces. Internet-based development also allows the service to save money that would otherwise be spent on travel to training facilities.

Providing the opportunity for a college education has been an important part of the Army experience for the past half century. In January 2001, the service launched an ambitious program to allow enlisted personnel to earn college credit through online courses. Called eArmyU, the program is built around a state-of-the-art Web portal that provides students with access to schools, courses, resource materials and support services.

According to Susan Johnson, eArmyU program adviser, Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, Crystal City, Virginia, the effort was designed to offer any time, anywhere access for an often highly mobile group of people who may be deployed overseas on short notice. The program has proven popular among enlisted personnel, she adds, noting that it easily met its first-year enrollment target of 12,000 participants. Both eArmyU and its portal are designed to be scalable. The long-term goal of the program is to provide college education across the Army, serving an estimated enrollment of 80,000 to 90,000 soldiers.

Twenty-three colleges and universities now participate by providing more than 4,000 courses for eArmyU, says Barbara Lombardo, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) eArmyU project manager, Arlington, Virginia. The first dozen students graduated from the program at the end of 2001. These soldiers had some college credits when they entered the program, she explains.

The heart of the program is the eArmyU portal, designed as a one-stop shop for students. When personnel log in for the first time, assessment instructions help them determine possible career choices as well as their readiness for college. Soldiers then create a degree plan with a specific institution. The portal also tracks their progress toward that degree by posting grades and allowing administrators to monitor student progress.

Johnson believes the portal is unique, noting that most other portals simply pass users through to other Web sites. “It’s rather a significant model as far as having everything at our fingertips through the technology solution. Nobody else has ever quite put this kind of model together, so there is a very significant undertaking here,” she says.

eArmyU’s portal also is designed to integrate with other Army legacy systems so that the registration process and student record functions are automated. This allows the program to draw on existing Army databases to keep student records up to date.

To be eligible for eArmyU, soldiers must have a high school diploma or equivalency certificate, at least three years of service remaining and be stationed at participating sites. The program is available to active duty troops as well as active duty National Guard and Reserve soldiers. Personnel interested in eArmyU visit Army education counselors at their posts. The soldiers’ academic history is discussed, to determine whether they have any prior classes or academic credit that can be applied to the program. This information is used to advise individuals about specific degree programs that best fit their goals and backgrounds and the participating schools that offer the best match in courses. Soldiers must then get authorization from their unit commanders. If approved, students may then log on and apply to their school of choice. The program uses a common application for all participating institutions, Lombardo explains.

Several goals were behind the Army’s development of eArmyU, Lombardo explains. One was to create a technology-savvy enlisted force that possesses the skills necessary to use and adapt to new, sophisticated equipment. A second objective is to increase soldier retention. “As with all employers, the Army recognizes that it is more effective and efficient to retain a current soldier than to recruit a replacement,” Lombardo says. She notes that 15 percent of the soldiers participating in eArmyU have re-enlisted or extended their terms because they must have at least three years left in their enlistment to be eligible to participate.

The third target was to help service members achieve their academic goals. Although the Army historically has been committed to helping soldiers meet their educational needs, course work often has been deferred to meet the demands of active service, Lombardo says. Now, because of ubiquitous, easy access to online education, Army personnel no longer will have to make that choice, she maintains.

When soldiers enter the program, they are given a technology package consisting of a laptop computer, portable printer, Internet access and an e-mail account—all supported by a 24-hour help desk that can be accessed via telephone or e-mail. In addition, students have access to online tutoring and Galileo, an online library designed by the University of Georgia. During the early stages of the program, PWC staff will remain onsite to provide additional technical support for the equipment. New participants attend a class where they receive their technology package and learn how to use the equipment. Lombardo notes that the on-base support will eventually transition to a completely virtual presence.

eArmyU was initially launched at three bases: Fort Benning, Georgia; Fort Hood, Texas; and Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Eight additional facilities will join the program by the end of 2002. In the program’s first year, participation was restricted to soldiers assigned to these posts. Lombardo adds that troops from these bases have been deployed to 10 countries in Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

Demand for classes has been overwhelming. Lombardo notes that soldiers waited in line overnight to apply for the program when it was introduced in January 2001. While the program easily met its target numbers for the first year, an ongoing challenge is how quickly and effectively the Army and PWC can roll out the program beyond the initial three posts, she says.

The 23 participating schools range from community colleges to state universities and educational institutions that operate online exclusively. eArmyU offers certificate as well as associate’s, bachelor’s and master’s degrees across many academic subject areas. Lombardo notes that some of the most popular degrees are in management, computer science and criminal justice. Schools in the program guarantee that student credits are transferable to other participating institutions.

Because soldiers often change posts or are deployed overseas, schools that are part of the program may require no more than 25 percent of an individual’s degree credits to be from the primary, or home, institution. This allows previous credits to be transferred from pre-military academic experiences as well as from other courses completed during a soldier’s enlistment. Military training and experience may also count toward a degree. The American Council on Education has created recommendations to recognize certain types of military training that can be applied toward college credit.

All course material is asynchronous—the classes are not held in real time. This was one of the Army’s requirements because soldiers could not be expected to be consistently available at a specific time of day or week for synchronous activity, Lombardo explains. Another consideration was bandwidth. Unlike civilian online universities or corporate training programs that use a company intranet, the courses must be geared to local dial-up conditions for wherever a soldier is stationed.

Setting up the program posed several challenges. Lombardo cites the example of a student administration system developed by PeopleSoft that is a key piece of software for the portal. Typically a college or university will take up to two years to implement the software system fully. PWC implemented it in four months. “We had very aggressive milestones established by the Army from the beginning of the program. The faster the portal was developed and truly integrated, the more quickly we could begin to serve soldiers and offer them full functionality,” she says.

Another challenge was to effectively meet the overwhelming demand for the program within the service. “I think this program really struck a chord with the enlisted soldier. It resonated with them and their needs,” Lombardo says. She notes that an ongoing challenge will be rolling out the program in an efficient and effective manner to meet the Army’s vision.

eArmyU planners are aiming at 2003 as an approximate time to go Army-wide with the program. However, Johnson is sanguine about the effort’s prospects, noting that although it has had initial success and has the support of the service’s senior leadership, funding is inadequate. “Many soldiers have told us that this is the best thing the Army has ever done for them. It certainly has minimized the barriers many of them have experienced in trying to pursue higher education,” she says.

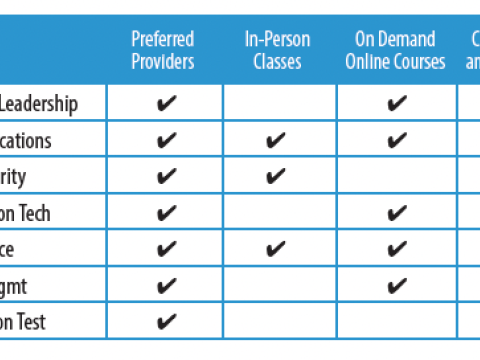

While providing a college education is helpful for personnel retention and individual growth, The Army Distance Learning Program (TADLP) seeks to hone soldier’s military skills. Traditionally, this type of training took place at specialized facilities operated by the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), says David Dryden, chief, horizontal integration, TADLP, Newport News, Virginia. By pursuing online training, soldiers do not have to leave their home stations, which saves travel expenses and improves morale because troops do not have to continually move to different facilities to get their required skills, he says.

Initiated in October 1997, the program is about 50 percent deployed. However, additional components such as learning management and courseware software are still in development and will not come online for another 18 to 24 months, Dryden explains. Training facilities with two-way video, audio and computer workstations are now operating at Army bases in the continental United States and in Korea, Japan and Europe. Prototype deployable training stations for use in forward bases also are being developed. One of the program’s goals is to have a training facility within 50 miles of anywhere Army personnel are based. This includes National Guardsmen and reservists as well as active duty troops, he says.

Training courses are provided via the Global Information Grid. An ongoing part of the program is to develop Web-enabled courseware and management software to operate across the system. Dryden notes that PWC is working with the Army to develop these software systems. One of the challenges faced in developing both the software and course material is that no standards currently exist, he observes.

TRADOC is developing courseware for TADLP by redesigning existing training material to fit into a distance learning format. The command is examining those skills that lend themselves to the medium.

“Obviously there are some skills that you cannot train for using distance learning. You actually need an instructor there or you may need a training facility in the field,” Dryden maintains. However, he notes that approximately 500 courses have been identified that can be restructured for online presentation. The Army plans to deliver some 30 Web-enabled courses each year for the program.

Because bandwidth is an issue in delivering course material, the service is taking a hybrid approach to training delivery. While the goal is to provide the bulk of training material online, not all facilities have the bandwidth resources. Under those conditions, high data content such as video, color pictures and interactive material will be provided through CD-ROMs, while low-bandwidth material such as text will come through the Web, he says.

Additional information on the U.S. Army’s distance learning initiatives is available on the World Wide Web at http://www.earmyu.comand http://www.tadlp.monroe.army.mil.

Comments