Materials Research Aims to Cool It

Heat is the enemy of sensitive electronic equipment, threatening performance and longevity. Now it could meet its match in an academic laboratory designed to find new ways of cooling delicate circuitry and devices. In January, Georgia Tech’s Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology, its Strategic Energy Institute and its Institute for Materials plan to open the Heat Lab, a unique center that is a collaboration between the Atlanta-based university and industry to develop innovative solutions to thermal problems.

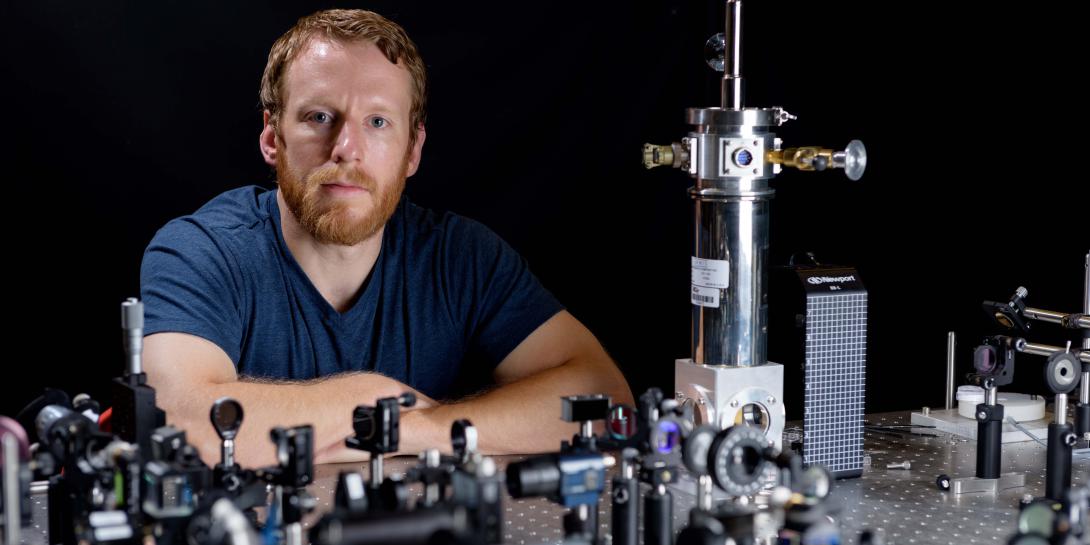

At the same time, a team from the university’s NanoEngineered Systems and Transport (NEST) Lab is pursuing pioneering research in thermal science, including intense studies of polymers to dissipate heat, says Tom Bougher, the Georgia Tech doctoral student who will head the new Heat Lab after he graduates in December.

The science behind managing heat flow, particularly on a small scale, is both underappreciated and misunderstood. The Heat Lab seeks to clear up confusion about thermal transport properties, which are often puzzling because proper characterization requires specialized techniques and expertise not widely available, says Bougher, who was a combustion engineer at San Antonio’s Southwest Research Institute before deciding to study nanotechnology and new energy technologies.

“We’re pooling all of our thermal characterization equipment and resources together to use in this facility,” he offers. “People can come from outside to use our equipment, or they can contract with us as we work to really narrow the gap between industry and academia. We can offer expertise while gaining a better understanding of industry needs and requirements.”

The lab will bring together more than 50 one-of-a-kind thermal characterization techniques to accurately measure thermal properties for even the most exotic of materials, including nanoscale types. It will boast 25 affiliated faculty members and more than 100 graduate students in thermal science and engineering who are primed to solve tomorrow’s thermal problems and find solutions to the daunting challenge of dissipating heat, Bougher says.

Until he takes the helm at the Heat Lab, Bougher and the NEST team are conducting research that focuses on heat generated by the use of electronic devices as well as the performance of polymers in ambient heat. They are developing new materials for thermal management: specifically, thermal interface materials placed between surfaces. The polymer materials replace air pockets that occur when two surfaces do not touch. Air is a poor conductor of heat, and the polymer materials—usually thermal insulators—do not perform well in high temperatures.

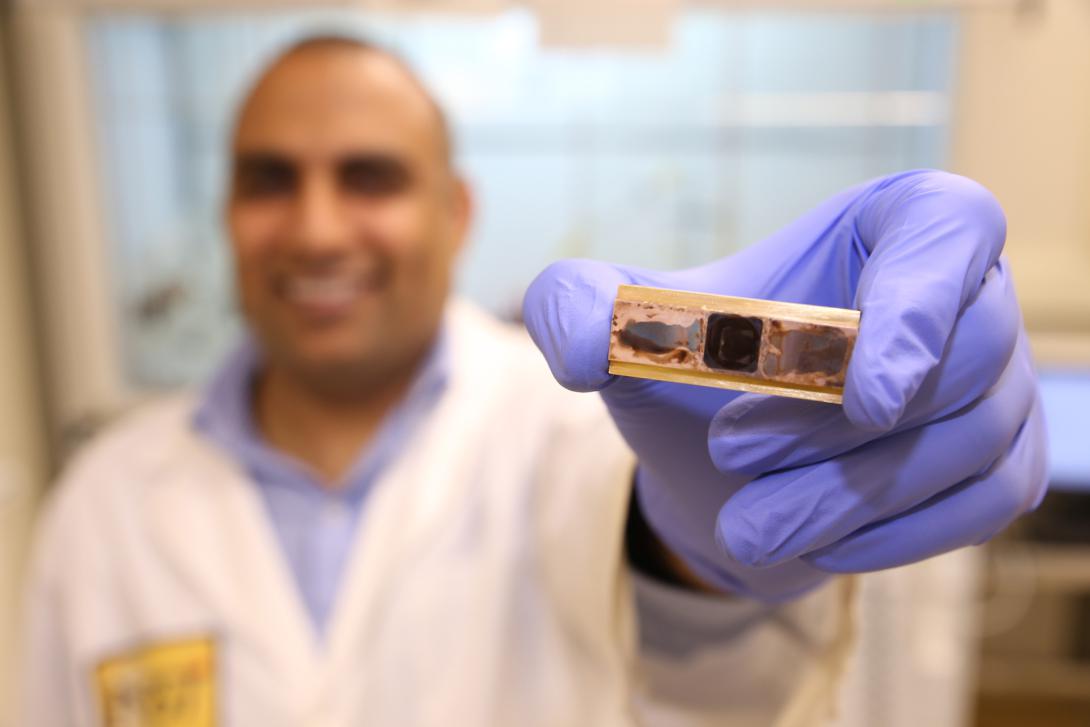

The NEST Lab, which is charged with exploring new materials that would help develop energy solutions, has been tackling a process called electropolymerization to produce polymer nanofibers that line up next to each other rather than present themselves in random tangles. The process not only strengthens the polymers, but also creates a thermal interface material that effectively conducts heat. Testing has so far proved the polymers reliable for more than 100 hours at temperatures of 200 degrees Celsius (392 degrees Fahrenheit).

The material could be used in the automobile industry and certainly within a military setting, Bougher says. Other applications could include servers and light-emitting diodes, or LEDs.

“Polymers are a plastic,” he says. “In a very broad sense, plastic is just a tangle of individual chains. When they’re just in a random tangle, you can think of them the same way as with threads; they’re not very strong, and there is no strength there because there is no orientation.”

But if the individual threads or chains line up in the same direction, they become stronger and more like a rope, Bougher explains. “A lot of times, the heat conduction can be analogous to creating mechanical strength when you’re talking about a plastic,” he offers. “When you line [up polymers], they become mechanically stronger, but they also tend to conduct heat better.”

Normal plastics do not tolerate high temperatures and typically melt. “But we use some special exotic polymers that actually have very good temperature stability,” he continues.

Because plastics have a pretty low density, they typically are lightweight. Using the polymers would not add weight to existing materials, and in some cases, they might weigh less, Bougher says.

In the future, the NEST Lab’s solutions could apply to the mobile electronics that troops might carry on their bodies. But for now, the focus remains on applications in vehicles. The polymers are “very well-suited for certain higher temperature applications, which is certainly a lot of the military electronics that operate at higher temperatures compared to consumer electronics,” Bougher notes. “We think there is some potential there, where it could work in harsher environments. There is certainly a need for that for military applications.”

Testing now centers on dissipating generated heat. Later, he says, scientists might investigate effective ways to capture and transfer the heat for other applications: “If you’re pulling heat away from electronics, you could move it somewhere else afterward, but our primary goal is really just being able to move the heat away from electronics quickly and efficiently.”

The nature of this work has led to logical partnerships with other departments at the technical university to facilitate the team’s research. Bougher’s group of 10 collaborates with chemistry colleagues who helped develop a synthesis of existing polymers. “We’ve taken certain polymers that are available in research for different applications that aren’t very common and pulled them in to use for what we’re doing,” he remarks. “There is a lot of really interesting research right now in organic electronics, which is actually using polymers as electrical devices and transistors and LEDs, and some of those polymers have really interesting properties for heat conduction as well.”

Comments