China in Space

China’s activities in space have caught the attention of U.S. and other countries’ officials, altering how personnel must consider the domain. The importance of the area outside of Earth to military operations makes the location critical for any nation looking to put itself into a terrestrial position of power. During 2012, China conducted 18 space launches and upgraded various constellations for purposes such as communications and navigation. China’s recent expansion into the realm presents new concerns for civilian programs and defense assets there.

In the U.S. National Military Strategy, officials discuss their concern about China’s military modernization and assertiveness in space, also stating that the “enabling and warfighting domains of space and cyberspace are simultaneously more critical for our operations yet more vulnerable to malicious actions.” The United States has released several pieces of guidance on its approach to the domain such as the National Space Policy and the Defense Department’s National Security Space Strategy. The military defines the latter as a “pragmatic approach to maintain the advantages derived from space while confronting the challenges of an evolving space strategic environment. It is the first such strategy jointly signed by the Secretary of Defense and Director of National Intelligence.”

Unlike the 1960s-era space race when Soviets and Americans competed to be first, China approaches space with a different set of goals. Dean Cheng, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation who focuses on Chinese political and social affairs, explains that the Sino perspective asks, “What do we want to do in space? What can space do for us?”

The answers have evolved over time. “In the ’90s and early 2000s, it was to facilitate national economic development,” Cheng explains. “That was true for many aspects of their society. The Chinese view themselves still as a less developed power. They want to develop themselves into a more developed power.” First forays off the planet focused on communications satellites to tie people together or navigation systems to help with urban planning. Only recently did the country start to look into early warning for ballistic missiles. Much activity still centers around prestige and political legitimacy.

A couple of months ago, large amounts of discussion in the China analysis community and beyond chattered about whether the nation is putting up a network of early warning satellites. Press reports have covered the launches, but Cheng says the Chinese themselves have not released an official announcement. Some analysts worked diligently to try to track down validating sources. It certainly is not outside the country’s technological capability, but if true it marks a differentiation from prior space missions.

Cheng says that despite some reports to the contrary, China releases information often on its various government activities. Whether or not other nations have the personnel to read them is a different challenge. On space specifics, however, he says China is virtually silent. Certain successes are promoted and covered in the mainstream media, including the missions to send humans into space and the docking of Chinese spacecraft with its orbiting space lab Tiangong 1. Now that China is comfortable docking there, information suggests a bigger facility will be created around 2020. However, much uncertainty still surrounds plans until new launch vehicles are unveiled. Cheng says decision makers should avoid the mistaken impression that China buys or steals its assets related to space. “The evidence is pretty strong to show that’s not all true, not to say they don’t engage in espionage,” Cheng states. But China modifies and studies design, adding its own touches as appropriate.

Beyond direct competition and potential conflicts in space, another concern is congestion. As more countries launch equipment into orbit, the area naturally becomes more crowded. Collisions already have taken place and more are predicted, a problem U.S. Strategic Command actively is working to address for continued function and safety. An anti-satellite test by China in 2007 that destroyed one of their own orbiters created a large amount of excess debris. That test also sparked tensions between China and other nations about capabilities and future plans.

The way the Defense Department operates now mandates freedom of operations in orbit. “From our side of the Pacific, basically space is an absolutely essential element of how we fight our wars, to the point where I suspect many don’t think about how reliant we are on space,” Cheng explains. It enables missiles and GPS, for example. It allows communications on and into the battlefield. Even weather satellites are essential, because atmospheric conditions have major impacts on operations and planning. “Basically, if we want to fight a war the way we have fought wars over the last 20 years, we need space,” Cheng states.

And China knows this. “The first thing to realize is that the Chinese read everything we write,” Cheng explains. Their military is a learning organization and closely analyzes results from recent wars at least back until the first Gulf War. Cheng shares that despite China’s overall reticence to release information on its space program, one subject it does write about is the importance of space and the need to establish information dominance and superiority, which requires space dominance. Establishing this power will be critical to success if there is a conflict, and China wants this edge over multiple potential adversaries including Japan and India, though the United States is the gold standard. “If you can take on the Americans, you can take on anyone,” Cheng says.

So, is the United States aware of these potential challenges in the space domain and the full capability of possible enemies? “If you’re our space warriors, sure,” Cheng says. But as that question moves from the uniformed to the civilian arena, more questions surface about what people know and what they take seriously. Perhaps even more concerning is what leaders really understand. Cheng emphasizes that leaders must avoid the pitfall of expecting China to mirror U.S. activities.

China will not necessarily need and use space in the same way as the United States. For one, physical differences in location have an effect. If the United States and China battle in the Middle East, then both will require over-the-horizon capabilities. But such a scenario is less likely than a skirmish in the Asia-Pacific littoral environment. At that point, when Chinese troops are thousands of miles from their coast and the United States is tens of thousands from its shores, space will mean a lot more to the latter than the former.

Furthermore, China’s space equipment is different from U.S. assets, developed differently with different priorities. Laws of physics might dictate what a rocket looks like, “but policy determines what space architecture looks like,” Cheng explains. The Asian gargantuan has laid massive series of fiber optics trunklines in its borders, so within the country itself there is no need for satellites. Even air power planning can be done largely with this fiber-optic structure. U.S. air power will have a harder time coordinating mission pieces from places like Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, or even Kadena Air Base, Japan, without space resources. That creates an asymmetry of power should orbiting capabilities become disabled. Combine China’s large air force without the same reliance on space with a massive fishing and merchant fleet that can bring in maritime information awareness without space, and even though neither will be uncontested, the equality of power shifts if space-based assets become disabled.

The problem facing the United States and others is trying to gather information to help make decisions. Cheng points out that unknown factors, at least in the unclassified realm, involve basics such as the size of the Chinese space budget, whether defense, civilian, manned, unmanned or any other facet. Even within the satellite weather program, the major players are unknown. It is not clear who sets priorities or what the decision-making process is either, according to Cheng. Finding the answers is hard for a few reasons, including the fact that though a respectable number of analysts study the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), Chinese space work is not a major focus of the academic community. The U.S. military is becoming more focused on China’s space activities, as demonstrated in various publications and reports. Unlike enemies in recent conflicts, China in theory can conduct much more sophisticated attacks, especially as its satellite capabilities increase. However, Cheng says, while capability and competition affect U.S. space decisions, other factors such as acquisition processes and sequestration may have much more effect.

China’s space activities are not all military, but its program falls under a PLA division and its senior leader. Increasingly, China is deploying systems that will fulfill military requirements; civilian assets can, and in an emergency will, serve defense purposes. Cheng explains that this applies even to the manned and lunar exploration programs. “China’s space program is run by the military—that’s what really matters here,” he states. “For anyone thinking about collaborating with the Chinese on space, understand the PLA runs their space program. When you deal with the Chinese on space, at some level you are dealing with the PLA.” Cheng also believes people in the U.S. defense, intelligence and homeland security communities should understand that decision makers in China do not necessarily think about issues the same way as they do. That concept has implications beyond space on such aspects as electronic or network warfare. Space is a means to an end. When the Chinese consider attacking space assets, the ultimate target is really the data, so nations such as the United States need to focus on defending that.

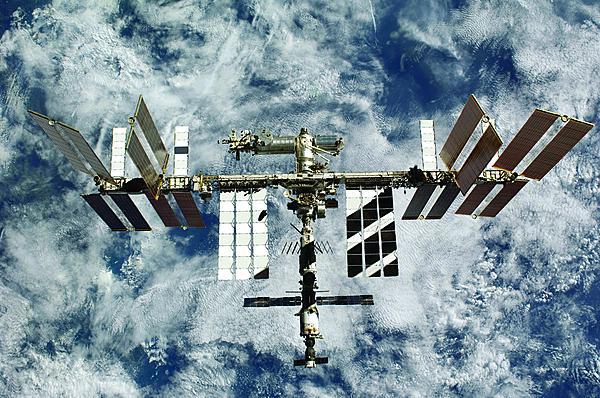

Away from the military, space can be a collaborative environment, as evidenced by endeavors such as the International Space Station and multination astronaut training. But even there, cooperation with the Chinese seems unlikely. Officials at NASA say that pursuant to U.S. law, “NASA does not collaborate on a bilateral basis with Chinese entities, including the Chinese space program.” And according to them, China’s plans matter little to schedules for the U.S. organization, explaining that while they applaud China’s space exploration efforts, if China sends humans to the moon, “such an achievement would not impact NASA’s current or planned activities.”

Officially at least, even talking about Chinese ambitions with the agency’s many partners is not on the table. The NASA personnel say they are “not having discussions with any country about the space exploration activities of the People’s Republic of China. NASA frequently has conversations with other nations about opportunities for civil space cooperation. Currently, NASA has more than 600 active cooperative agreements with more than 120 countries that touch almost all aspects of NASA’s activities.”

For China, collaboration also may have no value. Consider the space station. As it approaches the end of its expected usage, few incentives exist for new participation. In addition, Cheng says, China would be unlikely to join the effort at this point because it is “very, very, very, very, add a couple more verys” concerned about being equal. Cheng believes that cooperation on a trip to Mars is more likely because no one has done that yet and participants would all be in on the ground floor. “Personally, I think it would be a catastrophe,” he adds. The United States and China have no record of collaborating on major projects, and the first time probably should not be a high-profile, highly politicized process with high and unknown expenses wherein failure will have repercussions across government and the whole of society. Choosing a less ambitious project first would allow players to become more moderately familiar with one another, a process that has been difficult to date. Cheng suggests starting with tasks more along the lines of data sharing for China’s lunar programs and U.S. space explorations, agreeing on data standards. Concerns about collaboration are valid on both sides. With the vagaries of the U.S. budget, another country might legitimately hesitate to sign up for a long-term project that could be cut by a new administration.

(NOTE: The Chinese government did not respond to requests for comment for this article.)

Additional related links:

Comments